2015 Japan Retreat

By Tetsunori Koizumi

“Since the time heaven and earth parted, stands in Suruga the divine and lofty peak of Fuji, soaring high into the sky,” goes the opening line of a poem by Yamabe no Akahito (700?-736), which is included in Manyoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), compiled in the eighth century during the Nara period. The poem exemplifies the sense of awe and reverence the Japanese have expressed throughout history towards the highest peak in the land.

2015 Japan Retreat

By Tetsunori Koizumi

“Since the time heaven and earth parted, stands in Suruga the divine and lofty peak of Fuji, soaring high into the sky,” goes the opening line of a poem by Yamabe no Akahito (700?-736), which is included in Manyoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), compiled in the eighth century during the Nara period. The poem exemplifies the sense of awe and reverence the Japanese have expressed throughout history towards the highest peak in the land. Indeed, Mt. Fuji has been a source of inspiration for generations of poets, including Saigyo (1118-1190), a Buddhist monk known for his waka expressing mujo, or the sense of impermanence, and Basho (1644-1694), the author of The Narrow Road to Oku, known for his haiku of subtle sensibilities. As for works of visual art, many people are now familiar with the striking representations of the beauty and majesty of Mt. Fuji captured in woodblock prints by such masters as Hokusai (c. 1760-1849) and Hiroshige (1797-1858). It comes as no surprise, then, that in 2013, the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO decided to designate Mt. Fuji as a cultural heritage site and register it under the title, “Mt. Fuji: Object of Worship, Wellspring of Art,” in recognition of its enduring role as a source of inspiration for the Japanese.

Mt. Fuji continues to stand as the most representative symbol of the Japanese love of nature and aesthetic sensibilities.

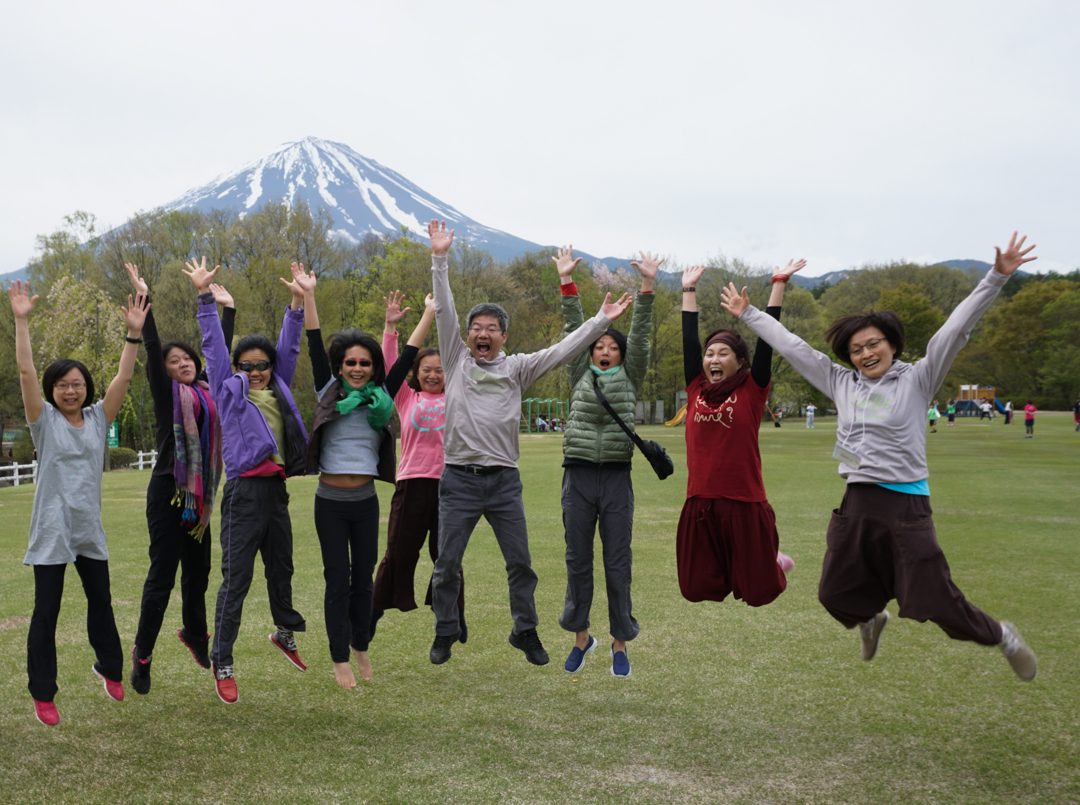

Given such background, it was quite a coup on the part of the organizing committee for the Thich Nhat Hanh 2015 Japan Tour to secure a holiday park at the foot of Mt. Fuji as the venue for the May 2-6 retreat during Golden Week, the peak tourist season in Japan. From the ground around the holiday park, participants were able to look up at the divine and lofty peak of Fuji in Kai, present-day Yamanashi Prefecture. The five-day retreat was a highlight event of the Japan Tour, which included a Dharma talk for the general public attended by 1,100 people, a Day of Mindfulness for 270 businesspeople, another Day of Mindfulness for 460 medical professionals, a Wake Up event for ninety young people, and a dialogue between Plum Village monastics and ninety Japanese Buddhist priests, all held in Tokyo. For the members of the organizing committee, it was a culmination of the hard work they had started a year earlier when they decided to take on the challenge of inviting Thay back to Japan, twenty years after his last visit. It was a memorable event for all 480 participants, including 115 participants from abroad representing eighteen countries, for we could not imagine a better setting for the retreat themed “Peace Is Every Step.”

A NEW BEGINNING

One person who was conspicuous by his absence was our beloved teacher, Thay, who was unable to come to Japan because he was recovering from the serious illness he had suffered in 2014. But like the 2009 retreat in Colorado, which Thay could not conduct due to his sudden illness, the 2015 retreat in Yamanashi turned out to be a resounding success, for his monastic and lay disciples from Plum Village and other practice centers did an outstanding job of conveying their master’s teachings to the participants, as evidenced by close to two hundred Japanese participants taking the vow to embark on the Five Mindfulness Trainings at the transmission ceremony held on the final day. When we did walking meditation every morning, we could feel that Thay was walking with us, enjoying a thousand views of Mt. Fuji as clouds danced around its peak, constantly changing their formations in the crisp May sunlight choreographed by the wind. It was a perfect setting to appreciate “the world we have,” Thay’s message about the importance of living in harmony with the natural environment. “This experience (of participating in the retreat) was more than fantastic … it was indescribable,” a comment by a couple from the US, sums up the happiness and joy we all shared.

The collective energy of mindfulness generated by the participants is still with us in our daily practice at our respective practice centers and Sangha locations. For most Japanese participants who had no previous exposure to the Buddhist practice in the tradition of Plum Village—including the First Lady of Japan, Akie Abe, who took a day off from her busy schedule to join us on the final day—the retreat was an eye-opening experience. Phrases like “smile to yourself,” “go back to your breathing,” “touching the earth,” and “beginning anew,” which had no meaning to them before, have become words to live by in their daily practice. As one Japanese monk put it, the retreat marked a new beginning for Japanese Buddhism. To be sure, Japan is a Buddhist nation, with eighty-seven million people—close to seventy percent of the population—professing to be Buddhists, and seventy-six thousand temples scattered all over the land, at least one temple per five square kilometers. However, most Japanese who profess to be Buddhists are not practitioners, and most temples that call themselves Buddhist do not serve as venues for Buddhist practice for the ordinary Japanese. Many social commentators, including some Buddhist priests, go as far as using the somewhat derogatory term, “funeral Buddhism,” to describe the reality of Japanese Buddhism today. Offering funeral and memorial services is the major social function most Buddhist temples play, as well as their major source of income.

It is not surprising that those who are concerned about the role of Buddhism in Japanese society, including the members of the organizing committee, should turn to Engaged Buddhism in the tradition of Plum Village as a way to make Buddhism socially relevant and accessible to the ordinary Japanese. “We will pass on the word, among ourselves and to our children and grandchildren, about the high peak of Fuji,” concludes Yamabe no Akahito in his poem quoted at the beginning. This line summarizes the determination shared by the participants in the May retreat almost word for word, except that we could rephrase the last part as “about our experience at the foot of Mt. Fuji.” We are determined to continue our practice wherever we are, making sure to transmit Thay’s message, “one Buddha is not enough,” to our friends at home and abroad and to our children and grandchildren so that they, too, will embrace the practice of mindfulness, smiling to each other and listening deeply to each other.

Tetsunori Koizumi, a member of Blue Heron Sangha in Columbus, Ohio, is Director of the International Institute for Integrative Studies. His 2014 book, Reinventing the Wheel of the Dhamma: Buddhism, Modern Science, and the Path Towards Individual and Societal Transformation, examines the Buddha’s teachings in the light of modern science for their relevance to the twenty-first century world of global interdependence.