We all wish to return to a place where we truly belong, where we feel happy and at peace. Most of the time we feel lost, as though we are living in exile. People all over the world feel this way, constantly searching for an abode of happiness and peace.

We are not separate. We are closely connected with others. The ground from which we grow is our family and our society.

We all wish to return to a place where we truly belong, where we feel happy and at peace. Most of the time we feel lost, as though we are living in exile. People all over the world feel this way, constantly searching for an abode of happiness and peace.

We are not separate. We are closely connected with others. The ground from which we grow is our family and our society. Many young people today are not happy because they come from broken families or because their parents devote so much time and energy to making a living that they have little real time for them. In the past, parents raised children according to the cultural and moral substance of their tradition, but today, few adults transmit the values they themselves received. As a result, children are left without guidance or support, and they grow up not knowing what to do and what not to do.

Without receiving values and without worthy role models, young peoples' feelings of loneliness are intense. They have little knowledge or confidence about who they are or what they are doing, and their parents just tell them to earn a diploma and secure a good job. Human beings cannot live on bread or rice alone. We need to be nourished by culture and tradition as well. Parents who are too busy to transmit wonderful cultural elements to their children may feed them delicious meals, send them to excellent schools, and work many hours to save money for them, but this is not the way to love children. True love for a child comes from a heritage of true happiness between the parents.

After the family, school is the most important environment in a child's life. Our children spend six or seven hours a day there. A child who can be happy at school is extremely fortunate. When I was in third grade, my teacher wrote on my report card, "No talent. Needs to be better motivated." This caused a big internal formation in me, and I did poorly that year. My sixth grade teacher was more supportive, and I did well that year—I even received a prize of many books. Every time I wrote a good essay, he read it to the class, and, greatly encouraged, I went on to a writing career.

Like the family, school is a product of society. When the society is healthy, the family and the school are also healthy. If teachers are unhappy and filled with internal formations, how can they look deeply into their students and understand them well? The Parent-Teacher's Association is important. Teachers need to understand the circumstances of their students' families in order to educate the students appropriately.

To be healthy, we need a good environment. One very healthy environment is a good sangha, a community of happy and peaceful individuals, people who can smile, love, and care for us, whose presence is as fresh as flowers. When we meet someone with that capacity of peace and joy, we should invite him or her to join our sangha. If she cannot stay for two or three years, we can invite her to stay for a few months or weeks, or even a few days. The quality of a community depends on the capacity of each person in it to be happy. A good sangha is crucial for our transformation.

When someone comes to a community of practice, we should learn about his or her past and family in order to offer suitable methods of practice. In retreats offered to young people, we should take the time to understand their culture, roots, and society in order to offer appropriate teachings. If not, the practice will be unrelated to their lives. By asking a few questions concerning their loneliness and their identity, we can open the doors of their hearts, and they will begin to listen and join us in the practice.

A friend or a psychotherapist can also help us very much, just by listening to us. But many psychotherapists themselves are not healthy; they are filled with suffering. How can we feel confident working with a psychotherapist who does not apply his knowledge of psychotherapy to himself? If we find a psychotherapist who has time to live and to be happy, his listening can be highly effective and we will feel great relief. Psychotherapists also need to establish peaceful, happy sanghas, groups of friends who meet regularly to drink tea, practice sitting and walking meditation, and bring peace and caring to one another. Clients who have recovered can be beneficial members of such groups since they have already experienced transformation and can help others do the same.

The number of individuals anyone can help is small compared with the number of people who need help. Treating individuals is important, but we also have to help our society be well. But if we are spending hours doing charitable or social work, taking care of the sick and the poor, as a way to escape our own loneliness, our work will not be effective. If we carry too many internal knots inside us, no matter how much time and energy we spend working for the well-being of others, we will still be lost.

To grow well, a tree needs roots. We need to get in touch with our roots and our true identity. If we live with a good sangha for a while, we will find our identity and true person. The words "true person" were offered by Zen Master Linchi. One day, Master Linchi said to his students, "Brothers and sisters, there is one true person who permanently comes in and out of our being. Do you know that true person?" The audience was silent for a long time before one monk stood up and asked, "Master, please teach us. Who is that true person?" Disappointed by the monk's question, Linchi said, "That true person? What the heck!" No one understood his words.

Who is that true person? Can we be in real touch with him or her? Until we do, we will continue to be lost, unable to find our true heritage. We will not need a train or a plane to come home. We will be at home wherever we are. Being with a sangha, with those who have found their true heritage, is the best way to realize this. In a sangha, even if we just relax and do nothing, one day our true person will reveal himself or herself. Communities where people can come together and be guided in the direction of returning to their true person are very important.

Many teenagers come to Plum Village feeling abandoned and unhappy. They suffer from cultural and identity crises. They listen to Dharma talks, but these do not help. The most important thing for them is to be in contact with others their own age who are happy. These friendships help them contact their own true person. This is a basic principle of the practice. If you are a Dharma teacher leading retreats, please keep this in mind. Otherwise you only offer temporary relief—you will not touch the sufferings that are rooted deeply in people and bring about real transformation.

Individual transformation always goes hand in hand with social transformation. We may receive praise when we go on a solo retreat for ten or twenty years, seeing no one and eating only fruits and vegetables. But if, during that period, we do not meet anyone who could say something to upset us, how can we be sure that our anger and delusion have been transformed? If we are criticized and confronted with difficulties and still remain calm and happy, then we know that we have arrived at understanding, love, and insight, and our transformation is real.

The moment we feel happy, society already begins to transform, and others feel some happiness. When someone in society finds his true identity, we all find our identity. This is the principle of interbeing. The moment we come in touch with our true person, we become relaxed, peaceful, and fresh, and society already begins to transform. If we are pleasant and happy, the nervous system of those we meet will be soothed. Everything settles down when we put an end to craving, anger, and delusion.

Even though our society has caused us pain, suffering, internal formations, and illness, we have to open our arms and embrace society in complete acceptance. We have to go back to our society with the intention to rebuild it and enrich life by offering the appropriate therapies for its illnesses. People may not be ready to accept our ideas, our love, but we must make the effort. When a foreign substance enters our body, white blood cell production increases, and macrophages embrace and destroy the foreign body. Even foreign bodies that can play an important role in keeping our body functioning well are rejected. If we need a liver transplant, the new liver is subject to rejection since it is foreign to our body. The new liver is neither sad nor disappointed, because it knows that it enters our body with all its love. It tries to find a way to establish a good relationship with the body so that one day it will be accepted.

We are the same. When we return home—to Ireland, Poland, Vietnam, or anywhere—we have to use skillful means to weaken rejecting phenomena. Even if our return is full of good will, we can be crushed. Some medicines that can cure an illness become ineffective before reaching the intestines because of the stomach's acidity. To prevent this, pills are coated with protective substances, and the pill's content is not released into the bloodstream until the pill reaches the intestines. We should use the same principle to return to society. Rejection also exists in our own consciousness. Our bodies and minds often refuse things that can help us. The practice of peace is basic for our wellbeing, but since we already have habits, rejection is a common tendency. Many people think that if they accept new ideas or insights, their identity or security will vanish. They may cling to something they think of as their identity, but that is not their true identity. It is only an artificial cover that society has painted on them.

Look at a Vietnamese teenager growing up in America. In her are worries, despair, and problems just as there are in all young people. The cultural and social substances that she has picked up in America have built up her personality, and she thinks she is just that personality. But her Vietnamese tradition and culture are also in her, although in the form of not-yet-sprouted seeds. In this young lady, there is the substance, the personality, and countenance of a young Vietnamese girl that she has not been able to touch. She believes that what she has received from American culture is her true person. If someone suggests that she live in an environment that will help her be in touch with the Vietnamese seeds in her, she may become frightened. To her, returning to her Vietnamese roots is a threat. She is afraid she will lose her personality. Most teenagers feel the same—that if their present identity is dropped, they will not know where to stand. We should help them find their true person so that, gradually, they will be able to let go of their suffering. Concepts about success and happiness are a kind of coating that society has painted on them, and they mistake them for their identity. Vietnamese, Irish, American, Polish, everyone should return to their true person. That is the only way we will have a chance to transform ourselves and our society, and become our true person.

All of us need to return home along that path. When we return, we may want to introduce the practice of mindfulness to others. If we can help people see the essence of love and understanding, we might be able to help the situation. To rebuild our society, we need to bring about social balance and uncover the best traditional values. We are like a child who has crossed many mountains and rivers to find the right medicine for our mother's illness. We should tell people, "Please try this remedy. It may cure the illness of our motherland. If this medicine is not effective, let us look for another remedy together. Let us give our motherland a chance." We must go back to our society as a son, a brother, or a sister and accept everyone as our relative.

When we return home, we can live in the heart of society, but we should be careful to protect ourselves. People may reject us or try to destroy us, because they are afraid to lose what they are accustomed to. We can try to establish a sangha, a community of practice, an island standing firmly in the ocean that is not affected by social storms—a protected island where trees and birds can live safely without being threatened by strong winds or high waves. A sangha is an island in which we can take refuge. Vietnamese, Irish, Americans, Poles all have to do the same. Sangha-building is a way to break through the obstacles presented by society. In order to offer a therapeutic role, a sangha should acquire a certain degree of peace and happiness itself. There need to be a number of happy individuals who have found their true person and are relaxed, smiling, accepting, loving, and helpful. Once an island like that is strong, it can open itself to more and more people for refuge. One island can then become two, three, four, or more, depending on its capacity to share the practice. Forming a sangha is not difficult if we have support of friends on the path. To take refuge, first of all, is to take refuge in the island of ourselves and then in the island of a sangha.

These islands are communities of resistance. "Resistance" does not mean to oppose others. It means to protect ourselves, like staying inside the house to protect ourselves from the weather. We resist being destroyed by society's pollution, noise, unhappiness, harsh words, and negative behavior. If we do not know how to take care of ourselves, we may get wounded and be unable to help others. If we join with others to build a sangha that can nourish and protect us and resist society's destructiveness, we will be able to return home. Many years ago, I suggested that peace activists in the West establish communities of resistance. A true sangha is always therapeutic. To return to our own body and mind is already to return to our roots, to our true home, to our true person. With the support of a sangha, we can do it.

In the Lotus and Diamond Sutras, there are stories of our true heritage: There was a young man from a wealthy family who led a life of pleasure, always squandering his wealth. His father loved and cared for him very much, but he could not find a way to make his son aware of his good fortune. He could see that his son would suffer and become a beggar if he did not transform, but he understood that warning or blaming the boy would not help. So he made himself a jacket and wore it for some years.

Then, one day, he said to his son, "In the future, when I die, I know you will squander your inheritance. I ask only one thing. Please do not lose this jacket. Please always keep it with you." The father had secretly sewn one very precious gem into the lining of the jacket. The young man did not like the old jacket, but he kept it because of his father's request was so easy. After the father died, the son quickly spent his entire inheritance, and soon, as his father had predicted, he became very poor. He went many days without food. The Lotus Sutra calls him "the destitute son." Nowhere could he make a living or find happiness. He owned only the old clothes on his back, including the jacket his father had asked him to keep.

One day, the young man was running his fingers along the outside of the jacket, and he suddenly discovered the precious gem inside the lining. For many months he had been living in hunger and despair, and as a result he now knew something of life. He understood how it was to use his precious gem to rebuild his life, and he finally received the heritage his father had left for him. For the first time in his life he was happy.

Our true heritage is a gem. It includes understanding, responsibility, and knowing the way to live happily. The Buddha uses this image in the Lotus Sutra to teach us that we are all destitute sons and daughters squandering our true heritage, which is happiness. Our heritage is right in our hand, but we waste our lives, acting as if we are the poorest person on Earth. Now is the time to rediscover the gem hidden right in our jacket.

In the Diamond Sutra, we read about sons and daughters of good families who fill the 3,000 universes with the seven precious treasures as an act of generosity, and the more they give, the richer they become. We can do that too, because we too have innumerable gems. Each minute of our life, each hour of our day is a precious gem. If we live mindfully, smiling, each moment is a wonderful treasure. Thanks to mindfulness, we can hear the birds singing, the leaves rustling, and so many other wonderful sounds. We see the flowers blooming, the blue sky, and the white clouds. If we live in mindfulness, our baskets will be filled with precious gems. Every second, every minute, every hour is a diamond. We have been living like wandering destitute sons and daughters. Now, it is time for us to go back and receive our true heritage and live our days deeply and happily. Once we learn the art of living mindfully, people around us will benefit from our happiness. We will be able to offer one handful of precious gems to the person on our right, another to the person on our left, and we never run out; our precious gems will fill the 3,000 chiliocosms. Our heritage is so rich. There is no reason to feel alienated. At the moment we claim our heritage, we can offer peace and happiness to our friends, our ancestors, our children, and their children, all at the same time.

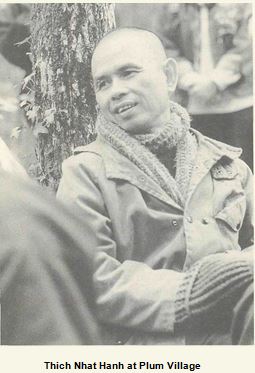

Adapted from Thich Nhat Hanh' s lectures at Plum Village, translated from the Vietnamese by Anh Huong Nguyen.

Photos:First photo by Ingo Gunther.Second photo by Karen Hagen Liste.

To request permission to reprint this article, either online or in print, contact the Mindfulness Bell at editor@mindfulnessbell.org.