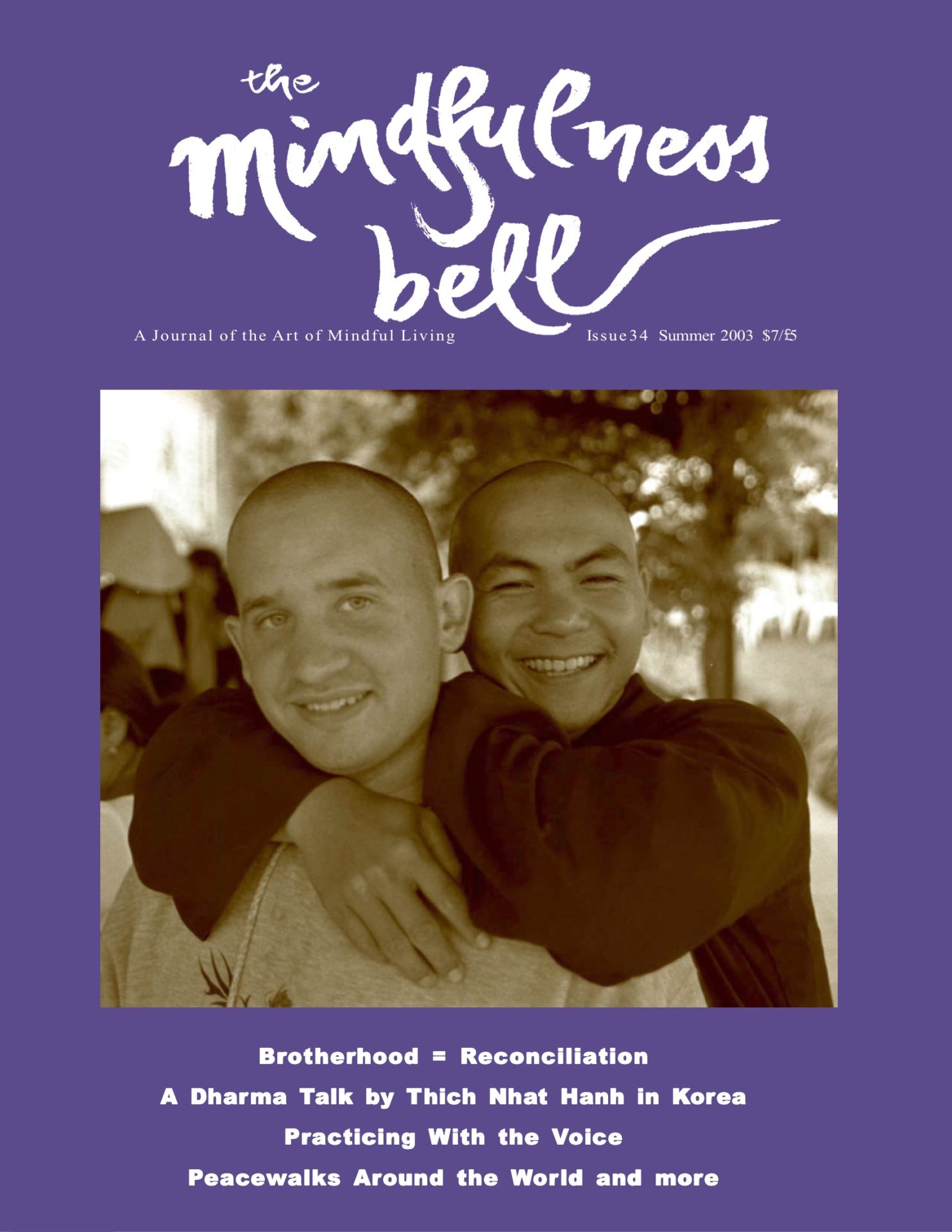

Brother Phap Uyen shares his path of practice

from Brother Phap Uyen’s writings and an interview by Sister Steadiness

My mom and I met Thay at a retreat in Redlands, California in 1989. I took the five mindfulness trainings and received the name Tam Houng, Strength of the Heart. Two years later I joined the military. I was seventeen and a half and I didn’t really practice the five mindfulness trainings.

Brother Phap Uyen shares his path of practice

from Brother Phap Uyen’s writings and an interview by Sister Steadiness

My mom and I met Thay at a retreat in Redlands, California in 1989. I took the five mindfulness trainings and received the name Tam Houng, Strength of the Heart. Two years later I joined the military. I was seventeen and a half and I didn’t really practice the five mindfulness trainings. Though my friends didn’t understand why I went into the military, it was my way of repaying the American servicemen that came to Vietnam and gave their lives so that I could come to the United States when I was two and have a better chance for education and a better way of living.

Entering Monastic Life

After coming home from the military and getting married I worked long hours every day because it helped me not to think about the problems I was having. Soon after Deer Park Monastery opened, my mom sent me there for two and half months to relax and try to change this habit.

My step dad and I had a hard time communicating when I was growing up. He went to Plum Village for the 2001 winter retreat, and when he returned we started trying to improve our communication. He suggested I go to Plum Village, so I went in the spring of 2002. I had fun during the Francophone retreat and the Vietnamese retreat. I started spending more and more time with the brothers.

I was planning to stay for the summer retreat and then return to the U.S. to start Chinese medicine school. After being trained to kill people in the military, I realized that I would rather use my hands to help heal people than use my hands to hurt people. I went to school for massage therapy and I wanted to study Chinese medicine as well. But when Thay’s Dharma talks started sinking in, I began to realize that if I became a monastic then I could help heal people’s mental problems or problems within themselves.

I wrote my letter requesting to be a monastic about two weeks before my ordination. I called my mom and when she heard that I was getting ordained she was very happy. She and my step dad, my sister, and my grandma came to Plum Village for my ordination, which made me very happy. My mom said, “If you love me then you will always take care of yourself and I hope being a monastic will make you happy.” Every time my mom calls me she asks, “Are you happy?”

Military Training

It was January of 1992. I had just arrived at the Naval Recruit Training Center. It was 0200 hours. We were all tired, but there was a drill instructor yelling and screaming at us. We were up until 0400 hours filling out papers, being put into companies, and finding out where we would be staying while we were being processed. We arrived at our barracks at 0415 hours and at 0530 hours a drill instructor came in banging on a metal trashcan to wake us up. We were the low-life of the military; we had not yet earned the right to be called sailors.

We had three months of training to learn to go into full combat situations with firing practice and live rounds. We had biological weapons classes and had to go through the gas chamber without our gas masks on. We also studied firefighting. Putting our lives in the hands of one another really united us. It broke our habit of being individuals and taught us to work together to achieve our goals.

After graduation from basic training I went to SEALS Training School. SEALS stands for Sea, Air, and Land. I enjoyed my time in the SEALS Training Program. I was in the best physical shape of my life. But there was something missing. I was getting physically stronger, but I was also becoming a non-human being. I was trained to do one thing: to kill and ask questions later. We were taught many ways to get into enemy lines undetected, blow things up, and neutralize targets and people. So when I was almost through with my training I reported that I wanted to leave.

During my SEALS training we would run, swim, and learn to paddle inflatable boats against the waves. We did a lot of push-ups, sit-ups, and ran five miles a day in the sand carrying eighty-pound packs. We studied first aid, hand-to-hand combat, a martial art called ninjitsu, firing different guns, blowing things up with explosives, and learning to make our own bombs. We learned how to use special weapons like machine guns, handguns, and knives. We were trained to kill people without them making a sound. We learned different joint locks and pressure points, how to jump out of planes, free fall sky diving, face first rappelling, map reading, how to communicate using military sign language, and how to disarm missiles, rockets, and bombs. We went through a survival program twenty-one day exer cise, where we were supposed to rescue a helicopter unit that had crashed on an island. Our instructors played the enemies. If we were caught we would become prisoners of war. They would torture us by hitting us with sticks, put bamboo sticks in between our fingers and squeeze them together, give us electric shock treatment, starve us, or lock us in small cages. They would try to get information from us, like where our command post was, which person was in command of the operation, or our mission briefing information. If our focus was strong then we would state our rank, our military branch, and our social security number, repeating this until we passed out. We were graded on this exercise and our leadership abilities as part of our graduation requirements.

In the last part of our training we went through hell week where we stayed up for the whole week, taking vitamins to help stay awake. To test our leadership abilities, we were put in a combat environment with guns and grenades exploding everywhere. We were trained to always rescue our fallen comrades and bring them home with us.

After making it through hell week, I had two weeks left of training before graduation. But instead I left. I saw that a lot of my friends were becoming meaner and more aggressive. It felt as if we had a switch that we could flip to change from being a nice person to a very dangerous, killing machine. Sometimes I saw that the switch could get stuck and we could not change back into a nice person. I felt like a wild animal because all I was doing was being trained to kill. Usually a SEALS class starts with about 300 to 500 people, but only ten to fifteen people graduate. I would have graduated at the top of my class.

Comparing Monastic Life to Military Life

The military and the monastic life are similar in some ways. In the military we woke up at five in the morning. In monastic life we also wake up at five o’clock to do sitting meditation. It helps us to concentrate and to reflect on ourselves. That is what I spend a lot of my time doing. In the military we didn’t have time for self-reflection because we were always busy.

As monastics we have time to rest. We do walking meditation, which I enjoy. We study our fine manners and our ten novice precepts.1 One of the most important things we do in Upper Hamlet is to build brotherhood. We also have a novice council. We talk with the elder brothers and decide what we want to do as novices. That way we have a say. When I was in the military we didn’t have a say in anything. The officers of the unit would just tell the lower ranks what to do.

Transforming Unwholesome Habits and Anger

I picked up some bad habits while I was in the service, like drinking and smoking, which I now have given up. A lot of special services people engage in unwholesome things like drinking, having casual sexual relationships, gambling, and spending money. Instead of living our lives to the fullest, knowing that we might not be around the next day, we did these things to forget and to not feel.

After I left the military my life was not good. I saw that I was losing some of my human qualities. Since I didn’t get along with my father, I didn’t go home. I hung around with some people that weren’t very nice. Some of those people still write to me, but I don’t respond to them like I do to other friends.

Military life is very aggressive. When I was in the military we were taught to react first and ask questions later. For example, if we had a problem with somebody else we wouldn’t talk to that person. Usually we would go to the bottom of the ship at night and fight it out until only one person was left standing. Other people would come down and watch the fight.

Even though I am a monastic now, still sometimes that energy of anger arises in me. When that happens, I try to come back to my breathing. I know that I shouldn’t say anything when I am angry. Instead, I do walking meditation or I go back to my room, make some tea, light some candles and incense and just sit there and enjoy the tea, looking out my window. Now I can control my temper much better. That is a big change for me. Another practice that I like is Beginning Anew. Every night before I go to bed I light some incense and candles on the altar in my room and I practice Beginning Anew from our Plum Village chanting book. I begin with the incense offering and go through the whole ceremony. In it, you repent for things that you have done wrong in the past, not just in this lifetime but for countless lifetimes before. You want to be brand new again. I also do Touching the Earth, which has helped me release a lot of anger and resentment towards a lot of things that have happened in the past between me and my family. It is also a big help to have supportive brothers and sisters, and my mentor who I can always talk to and ask for help.

Practicing with Physical Pain

One difficulty I have struggled with is that my knee, my ankles, and my back are pretty messed up due to the violent nature of my military and martial arts training. When I was younger I never thought about the effects that this training would have on my body. When I was training in martial arts, my instructor would make us break bricks and wooden boards with our bodies. As you advance in rank you can’t just punch the board or chop the brick with your hands, you have to use different parts of your body. I would always use my legs, since they were the strongest part of my body. That is why my knees are pretty messed up.

In addition, the bones on both sides of my vertebrae are cracked, so often it hurts a lot, especially at night when I sleep. I can get up in the morning to go to sitting meditation, but it hurts. Also I don’t want to disturb my brothers when they are sitting in meditation so I just sit in my room.

As monastics one of the main things we do is sit in meditation. Since I can’t sit very long, I feel isolated from the Sangha in some ways. But Thay Abbot, my mentor, has encouraged me to sit with the whole Sangha. If I can’t sit for the duration, he said to just sit for half the time and then do walking meditation. Or he suggested that when everybody else is sitting, that I do walking meditation instead of staying in my room. That is why I like to go for long walks as my way of doing meditation. I practice to embrace my pain when it is there. I am also aware that my pain is not always here; I can run; I can play volleyball too.

My Relationship with My Mentor

I can talk with my mentor, Brother Nguyen Hai (Thay Abbot), about problems that I am having or about problems with any of the brothers. I ask him for suggestions on how I can help build brotherhood between the Western brothers and the Vietnamese brothers. He is very understanding about the problem with my back.

I am also his attendant. It is a great opportunity for me because it helps me focus on the practice. When I walk with him it is like walking with my teacher and I am mindful of my steps and aware of what I am doing. He told me that I still need to learn to walk in a gentler way, because from the military I developed a strong way of walking.

Facing Another Challenge

During winter retreat one of my close friends came to visit. She’s been a practitioner of Plum Village for a long time. It was a little hard to be with her now that I am a monastic. During the holiday season she asked to give me a hug. I went over and asked my mentor and he said, I guess she can hug you, but it would be best if she didn’t. So I asked him to come and stand next to us while she gave me a hug.

She kept forgetting that I am a monastic now, so while we were walking together she would try to hold onto my robe. I would have to remind her not to do this. The feelings that came up in me were there for a couple of weeks after she left. Talking to my mentor and reflecting on my life I see that I care for her still, but my love for her is not romantic now. As Thay has said, we are human beings so sometimes that energy still arises and we have to know how to take care of it. I have talked to my mentor about it a lot.

Re-establishing Communication with my Dad

One of the biggest things that happened for me as a monastic is that I wrote a letter to my real dad in Arizona. It was the first letter I have ever written him. It has been really hard for us to communicate because he is a very traditional Vietnamese and he has a hot temper. That is probably where I get my temper. I have been trying to keep in contact with him because I know that my dad and his side of the family are suffering a lot. My dad is the eldest son in the family, which makes me the eldest grandson and I am the one who is supposed to carry on the family line. But now that I am a monastic that is not happening. My only sibling is my sister and my only child is a daughter, so I have no descendants that carry the family name. I know that has hurt my father. I try to explain that I have become a monastic because I don’t want to be a monster of society anymore; I want to help people and their suffering, and first I have to help myself.

It was very hard for me to talk to my dad because he regarded his viewpoint as the best one and he didn’t listen to what I said. In Asian culture when the grown-ups talk the children are expected to just go out and play. In the past when I tried to talk to my dad we would begin arguing after five minutes because we didn’t understand each other. But slowly that has changed. I call my dad every once in a while and ask how he is doing, and I tell him about my happiness. I don’t preach to him because I know a lot of my family members on my father’s side don’t have a strong faith in the church or in the Buddhist religion. Being Vietnamese, since we were small my grandma took us to the temple, so we say that we are Buddhist but a lot of my father’s family doesn’t have energy or faith in the practice. My mom has said that my being a monastic can hopefully change that energy on my dad’s side of the family.

My Relationship with My Daughter

My daughter’s mother and I divorced when my daughter was less than a year old due to our cultural differences. Her mother is Catholic and Hispanic and I am Buddhist and Vietnamese. We didn’t understand each other so it was really hard for us. When my daughter was born I was working and going to school at the same time. I would get home at eleven o’clock at night. As soon as my key touched the lock my daughter would wake up. I would play with her and she would smile. When we divorced my ex-wife moved to another city with my daughter, so I didn’t get to see her very often. Before I became a monastic I sold a car and set aside that money to pay my daughter’s child support. My sister and other relatives offered to help visit and take care of my daughter so I could become a monastic.

My mom is coming to Plum Village this summer and she will try to bring my daughter with her. In some ways I feel that being a monastic is the best way that I can help my daughter. I would rather be fully present for her one month of the year than to be around her twelve months out of the year and not truly be present for her.

Serving in Kuwait / The Suffering of War

I was in Kuwait from June to December of 1992. I now see that we were over there not because of the suffering of the people of Kuwait, but for the oil. I have met a lot of Iraqi people. They are great people, some are very friendly. Yet I also remember meeting some Iraqi villagers that were very hostile towards us American soldiers, and I couldn’t understand why. I thought we were trying to help them end the suffering that their government was causing them. I now know that they might have rather put up with the treatment from their government than have us come and cause more suffering.

In 1985 the United States sold biological weapons to Iraq. Iraq then attacked us in the Gulf War with our own weapons. A violent act towards others will bring a violent act towards you. So when the United States attacked Iraq during the Gulf War it helped September 11th to manifest for the United States. And when Iraq attacked the United States they were also causing suffering for their own people. They launched biological weapons into the air, which infected the Iraqi people and their food as well as their enemies. That is a big price to pay for oil and holding onto a point of view.

The biological weapons used in Kuwait on the United States service people affected some of my friends. The United States won’t admit that some of us contracted this illness, called Desert Storm Syndrome. I have two friends that have severe problems.

One is a sergeant in the Marine Corps. Two weeks after returning from Kuwait he lost forty pounds and experiences a burning sensation inside his body. His wife told me that he may have only two years before he continues in a new manifestation. He is only twenty-eight years old.

Another friend is also a sergeant in the Marine Corps. She has burning, red spots on her skin that break open and leak yellow pus. The doctors have given her some experimental medicine, but it is not helping. She is having problems with her boyfriend because she can no longer have a child. She is suffering a lot. She feels very alone now. I told her that she is never alone. She always has her parents, herself, and her close friends to help her and that we will always be by her side.

Insights From the War

When I look back on being a soldier, I see that we do protect the freedom of our country. But we must also protect the freedom of all other people and things. We shouldn’t see ourselves as higher or better than anyone else. All of us have come to be what we are due to a lot of things. The rich are not separate from the poor, the just from the unjust, the first world from the third world countries. We are like this because they are like that; they are like that because we are like this. To protect and support ourselves, we have to protect and support others. We are made of each other. We are each other. We experience the same suffering of violence, fear, anger, hatred, and discrimination. My experience in Kuwait taught me that much.

I believe that if our president and political leaders were the ones leading us into battle, putting their own lives on the line, then they would think more carefully before they go to war. They would have seen first-hand, for example, the suffering and destruction that happened when our missiles went off target and wiped out small towns.

I believe instead of fighting each other we should work together to end poverty, hunger, malnutrition, and homelessness. We should educate the children, care for the sick and old, and work towards peace for the world instead of fighting over oil, which doesn’t really belong to anyone except the cosmos. We cannot take oil with us when we die. We fight so hard for oil because we are greedy and fixed in our own point of view. Instead we need to focus on what is actually worth working for: peace and harmony in the world.

Serving as a Monastic / Helping Others

My martial arts training has helped me come back to myself. I don’t practice the styles that I learned in the military because they can easily make a person become violent. Now I practice tai chi and aikido to become centered. I am beginning to share this practice with the Sangha. I also learned how to cook in the military, and now I cook and bake cakes for the Sangha.

I am very interested in helping teenagers. When I got out of the military, I thought about becoming a teacher. I see that if we help the younger generation to build their wholesome seeds then we don’t need to be afraid. But if we help them to water their negative or harmful seeds then we have a lot to worry about because they are going to be our future leaders.

It brings me great joy, especially during summer retreat, to help Vietnamese teenagers. Even though I am twenty-nine years old I am still young, and at the same time, I have had a lot of life experience. I have been through the military, I have been married twice, I have a seven year-old daughter, and I have lived on my own. Many young people think that their parents are old and don’t understand what they are going through. They think they want to get away from their parents and live on their own, but they don’t understand what it is like to live on their own. Hopefully, by sharing my experience they can understand both the positive and negative sides of leaving home.

I know that I have a lot of transforming to do. A lot of people joke about my name, Dharma Garden. I asked Thay one day when I was his attendant, why Dharma Garden? He said, because you have a lot of seeds in you, both wholesome and unwholesome. As the gardener you have to transform the unwholesome seeds.

My Joy as a Monk

My biggest joy as a monk is being around Thay and my brothers and sisters. Sometimes I am sad about what is going on around me, because occasionally my brothers and sisters don’t act as I expect them to. But I am reminded by my elders in Upper Hamlet that just because we are monastics, we’re not saints, and we all have shortcomings. Sometimes I get discouraged because a brother might talk to me a bit harshly. But, if I truly care about that brother I will find out why he is acting that way. Often it is just because he is tired or has something on his mind.

One of my joys is offering massages to my brothers. Sometimes a brother will ask me why I don’t get tired, giving so many massages. But I don’t feel tired because doing this helps me connect to the brother that I am massaging. When we massage Thay, we follow Thay’s breath, and that is how I massage my brothers. Sometimes when I massage my mentor and I am not following my breath he will stop me and say, “What are you thinking about?” And I become aware that I am not totally focused on what I am doing.

Another joy is drinking tea with my brothers. Every day it is busy in my room because all the brothers stop by and we drink tea, we laugh and play. My room is like grand central station for the brothers before they go to other activities in Upper Hamlet. It is a real joy to have my brothers around.

Brother Chan Phap Uyen, True Dharma Garden, ordained as a monk in 2002 and lives in Upper Hamlet, Plum Village.

Sister Chan Thuong Nghiem (Sister Steadiness), is a nun in Plum Village.

(Endnotes)

- To read the ten novice precepts and the forty-nine chapters of fine manners for novices see Stepping into Freedom by Thich Nhat Hanh.

- See article in the Mindfulness Bell 33 about “Touching the Earth” practice and A text of Touching the Earth is also in the Plum Village Chanting Book (Berkeley: Parallax, 1999.)