Behind the Projections onto the Robe Part Two

By Lori Zimring De Mori

The author questions two young monastics on their journey from lay life to ordination. Part One of this article was published in the autumn issue of the Mindfulness Bell.

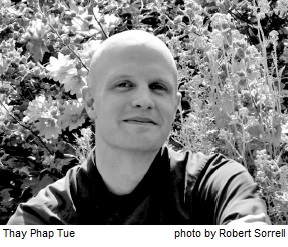

Phap Tue

Phap Tue, whose given name means wisdom, ordained as a monk in December of 1999.

Behind the Projections onto the Robe Part Two

By Lori Zimring De Mori

The author questions two young monastics on their journey from lay life to ordination. Part One of this article was published in the autumn issue of the Mindfulness Bell.

Phap Tue

Phap Tue, whose given name means wisdom, ordained as a monk in December of 1999. Growing up in Northern California, his passions were nature, soccer, reading, and the Grateful Dead band. During the summer of 2003 he helped run the children’s program at Upper Hamlet in Plum Village and with great intelligence and sensitivity facilitated the adults’ discussion about the Five Mindfulness Trainings. He is twenty-nine years old.

Thay often asks us to remember our fi experience on the path. What was yours?

Lots of the Vietnamese monks remember a feeling they had when visiting a temple. My family went to church on Sundays, and there I saw the seed of silence and something beyond the ordinary, but I was much more moved by the natural world, especially when I went down to the creek behind our house by myself. I was about five or six years old. Even as a child I had a propensity to be happy alone. The creek brought me into a silent space and seemed to open up my mind.

When I was in fifth grade I read a book called The Dragons of Autumn Twilight. It was about a group of friends on a spiritual journey to find themselves as individuals, and as friends, though the tale was clothed in mythological adventure. There were a few characters whose personalities influenced me deeply, particularly a mage, or wizard. The wizards lived virtually alone, deep in the woods, in towers, in mountains or in other hidden, mysterious places. They wore robes, had no girlfriends, and were entirely devoted to their practice. I see this character in me now. I think a Buddhist monk is quite possibly as close as you can get to a modern-day wizard.

So were you a quiet, solitary child?

Not at all. I was also a real talker and loved being in community, on teams. My dad was determined for me to play out that feeling in the athletic realm. He’d been a great soccer player when he was young but denied that first love in favor of more socially acceptable choices. Our relationship centered around competition and approval. I liked soccer, I liked learning, and I wanted approval, so in school I was a teacher’s pet and out of school my primary focus was being in nature and playing soccer.

How did those two sides of you—the solitary and the social—play themselves out as you got older?

My best friend growing up was a wild, free-spirited kid named Shane. He wasn’t a good student and he didn’t really care about people’s approval. I learned from him to be a bit more bold. By high school we’d grown apart. I was playing soccer on state teams. That made me popular and girls liked me but I was also becoming more of a loner. I started eating lunch with my English teacher who was a devout Christian. We’d talk about religion, politics, and literature. In my senior year I started reading Joseph Campbell. I had a strong spiritual inclination but it suffered from my devotion to soccer, where success was measured in terms of fame and recognition rather than through understanding. On the other hand, my coaches taught me discipline, focus, and concentration. They were very good teachers in many ways.

At the same time I started doing hallucinogenic drugs, mostly mushrooms. Mushrooms became my “spiritual path”—they showed me things about myself I’d never seen before. I’d take them every full moon and go hiking alone. I was getting in touch with the natural environment in a new way, but it was usually drug facilitated. I also loved the Grateful Dead. A whole group of us—mostly older than me—would follow them around the West Coast and go to all their concerts. We’d free dance, spinning around in circles. There was this ethic of peacefulness and love among Dead fans. We never saw each other outside of the concerts. When we left we’d just say, “Love you. . .see you next concert.” I fell in love with a girl who was always at the concerts. She was twenty-five, a vegan, and an environmentalist. I was nineteen. I didn’t tell her how old I was.

What did you do after high school?

I went to UC Berkeley and played competitive college soccer. I trained every day but didn’t really hang out with my teammates. We were friends on the field, but off the field I enjoyed other things than going to parties, drinking, or chasing women. So, I spent most of my time training, studying, and being alone in nature. Then I crashed.

What do you mean, you “crashed”?

I got injured during my freshman year at Berkeley and I just couldn’t come back from the injury. I couldn’t walk without pain. Yet the greatest pain was not the physical pain I experienced but the psychological trauma of losing who I felt I was. I fought with my old ideas of God and “what was meant to be.” I realized I wasn’t going to be able to play soccer competitively but I couldn’t really let go. I became angry and depressed, lost confidence in myself. I was so lonely, and yet didn’t want to be in a relationship. I felt like I had work I needed to do on my own. I realized I didn’t really miss soccer, that I loved dancing and hiking more. I had virtually given up alcohol and other drugs by then, and I began to distance myself from my old friends. In my sophomore year I moved into an apartment on my own. I still felt heavy and depressed so I just put all my energy into school.

Did you have any spiritual practice at this point?

Not at first, but two things happened which influenced me. I went to an exhibit of Tibetan sacred art at a place called Dharma Publishing. The gallery was lit by thankas, colorful tapestries with different deities, natural scenes, and silent stories. I was in a dark place in my life at this time, so this color was a great gift.

There was a lecture afterwards about the Four Noble Truths. It really touched me. It addressed my real experience and gave guidance in a practical way. I wanted to hear more. Dharma Publishing became my Sangha and I started going to teachings every Sunday. The teachings fit with the values of nonviolence and peacefulness which I already held from my Grateful Dead days, and I found them intellectually flawless. No dogma. No conditions. Just “see for yourself.” I started reading books about Buddhism and felt nourished by the teachings.

Around the same time I was up late one night flipping through television channels and a guy named Tony Robbins was advertising workshops to help people see what they wanted in life and teach them how to get it. His approach was not strong on the spiritual but he did talk about knowing what your values are, understanding that many have been inherited rather than chosen. His idea was to create a hierarchy of values and make them your target. But first you needed to discover what your values were.

I saw that I valued two things very strongly: one was compassionate understanding, which was in accord with my new spiritual awakening. The other was a value I hadn’t even realized was strong in me—the desire to influence people, to be seen as someone who could do things. I decided to leave that behind and to try to live without looking for approval. I wanted to be truly free. But I needed wisdom, understanding. I also needed to drop my fear of not doing well in school. I was often nervous about grades. I began to see this was another way I sought approval and recognition. I saw it was based on fear of rejection. So I made sitting meditation my new priority. I began sitting for two hours each morning. School became easier and more enjoyable and I found my happiness was not so much about what I did but what was inside. Compassionate understanding became my number one priority.

Were you practicing with a teacher or on your own?

There were lay teachers at Dharma Publishing and they were wonderful but I got to a point where I wanted a teacher “with the glow.” I had a friend who was practicing in Dharamsala. After graduation I told my parents I was thinking of going to Chile to teach or to India, to practice. I told them I was also considering the monastic life. They didn’t take me seriously.

I’d also thought about getting a teaching credential. My father said he’d pay for school if I got my credential before going away. I thought, “The practice can be done anywhere; I can practice at school.” So I took the opportunity, with one condition: I would study because I loved it. And I would not stress. So I went back to school, tutored kids, and coached soccer. I liked teaching and the kids liked me but I was aware that my love was always conditional, even to my students. I gave them attention but I didn’t really know how to love and understand them. Through meditation I was beginning to see clearly that I didn’t really understand myself, yet I was teaching. There was always an element of hypocrisy, for I still had insecurities and fears I needed to resolve.

In the meantime I was still sitting every morning and had started reading Thay’s books and I’d found a Sangha two blocks from home. It was very alive, deep, and honest. One morning I was sitting and I saw all these ideas I had about myself and suddenly thought, “It’s all a painting—you’ve made it all up.” This was one of the first deep realizations I had. As I continued to sit regularly each day, the meditation bore more insight. I remember one morning after I had sat I opened my eyes and felt extremely calm. Everything was silent. There was one of Thay’s books beside me: The Diamond That Cuts through Illusion. I opened it and read a passage. It spoke of a type of giving called “the giving of non-giving.” It meant you gave to someone without conditions, with no discrimination between self and other. I read this passage and thought to myself, “Is this possible? Is this true?” And a very honest voice, that was my own, rose out of me: “You know it’s true.” And then I thought to myself: “It’s over. That’s it. It’s all over.” I stood up and called my department counselor and told her I was withdrawing from the education program. I told my dad that he hadn’t wasted a penny but I had learned all I could learn and was going to become a monk.

Why did you decide to go to Plum Village?

I’d read many of Thay’s books—the Heart Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, and Your Appointment with Life. I thought that if the community of Plum Village practiced in the same way Thay set out in his books I’d be fine.

I wrote to Plum Village to see if I could come that summer and was told to wait and come after the summer retreat. So I decided in the meantime to go to Thay’s Green Mountain Dharma Center in Vermont to practice for a month. It’s very quiet and contemplative there. I ended up staying for six months before coming to Plum Village. I ordained a month after arriving.

How did your parents react to your decision to become a monk?

My mom was upset. At first she cried and yelled. More recently though, she’s come to visit me, practice with us, and has even taken the Five Mindfulness Trainings. My father was absent. When I asked him why he thought I was becoming a monk he said he thought it was because I didn’t know what else to do. My reasons were exactly the opposite.

Does anyone ever leave the monkhood?

Sometimes. Overall the percent of Westerners who leave is higher than non-Westerners. There were sixteen people in my ordination family. One has left already.

What is your practice like now?

There’s a communal feeling that comes from living in Plum Village. Sometimes I miss the quiet of Green Mountain Dharma Center in Vermont, but I believe that mindfulness and awakening can happen anywhere, at any time. I feel that practice should be engaged, not just on the hilltop. Otherwise I’ve really tried to let go of any expectations. I want to create harmony and to share. I’ve retired from sports and moved away from competitiveness to things like yoga and dance. I’m losing my sense of ambition.

Are you interested in teaching?

I don’t think about teaching too much yet. I still have thundering insights on the cushion then get up and start making judgments about others. In monastic life you’re often put up before others and expected to teach. I still prefer to train myself until I am a more stable practitioner. I know I can’t get up there egoless yet. I still want to be taught.

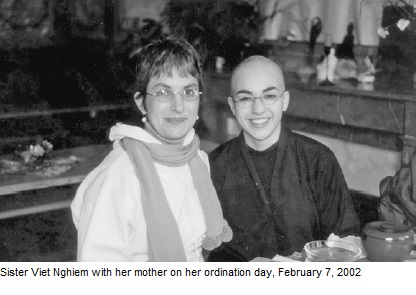

Viet Nghiem

Chan Viet Nghiem received the monastic precepts when she was twenty years old, in February 2002. Born in the north of France, she is one of the youngest Western nuns to have ordained with Thich Nhat Hanh. Her given name means “True Transcendence.” We spoke under the temple bell at Plum Village’s Lower Hamlet. She began our conversation by handing me a photo album. The first picture showsa bright-eyed baby; one of the last shows Thay cutting a lock of her thick, dark hair at her ordination ceremony.

What brought you to Plum Village?

My mom and I were living in Paris. She had come to Plum Village in the spring of 1997 and wanted to bring me back with her for a week that summer. We hadn’t been getting along, and she thought that with the help of the sisters at Plum Village we might learn to communicate better. I thought she wanted the nuns to “fix” me. The idea of spending a week with her at Plum Village sounded awful!

At the age of fifteen, I felt I had no preparation to face life and its challenges, at school and in my family. I often felt lost and hurt, and carried away by my emotions. I was discovering the presence of a world within me that I didn’t understand at all. I didn’t know how to communicate that to my mother. She wanted to help me, but she didn’t know that I would end up wanting to become a monastic!

How was that first experience?

I didn’t like it at all in the beginning. The distractions of society had been keeping all my fears and feelings of insecurity hidden. It was very overwhelming to face them all in the silence of this place. I wanted to go home but my mom insisted that we stay for the whole week. After three days I started to settle, and discovered a sense of home and safety within me. During Thay’s first talk, he asked an American and a Japanese to practice hugging meditation as an act of reconciliation. It was so powerful. I noticed that the sisters and brothers practiced to make everything sacred in and around them, just by breathing in and out.

Did you take the Five Mindfulness Trainings?

Not that first year; the ceremony scared me. I was shy and didn’t want to stand up and kneel in front of the sisters. But I really liked

my first retreat at Plum Village, so I made my mom promise we would come back for a longer time the following year. And that time I took the Mindfulness Trainings and they really helped me. I was in a teenage crisis, rebellious and reactive against the whole world. Taking the Trainings was a foundation for me to learn to respect myself and others. They were seeds planted in the soil of my being. They gave me guidance, something to help me “swim” in society, They were a light in the dark for me.

What happened?

Something changed in me, slowly but deeply. I went back to my environment with a powerful tool of protection. I could imagine the misery I would put myself through without the Trainings. I had hard times, especially with my friends and my boyfriend, and their influence on me. But I knew I had support from a spiritual community, and that meant a lot.

Thay helps people to “re-become” human. Back at school it felt like the teachers and other students helped me lose my human nature. It was all about good grades—not about acknowledging our feelings, our suffering. Thay teaches through his actions. This really made an impression on me. I could listen to a Dharma talk and have no doubts. I had a capacity to put it into practice, at my own pace. Sometimes I would cry, seeing the difference between the love that Thay embodies and the lack of sensitivity that I met in some of my teachers.

Is this when you decided to become a monastic?

Not really. I was almost seventeen and thinking about what I was going to do with my life. I decided I wanted to live in community. I didn’t want to marry or have kids and I didn’t want to work for money. I felt a deep aspiration for service, but I didn’t want to be a monastic. I wanted everything about monastic life but to be a monastic.

The Christmas after my second retreat my mom and I returned to Plum Village together. Sister Jina became the abbess of Lower Hamlet that winter. As I watched the ceremony, with the rows of monastics in their yellow robes facing each other, I realized that this was what I wanted to do. From then on I started coming to Plum Village to get to know the life of the sisters. I developed and found a deep support from them.

How did your mother feel about your wanting to become a nun?

I hadn’t told her at this point. I hadn’t told anyone, not even my best friends. But deep down I knew this was what I wanted to do. At eighteen, I graduated from high school and came to spend the summer in Lower Hamlet. I started helping in the teenage program.

When I came home from the summer retreat I told my mom that I was planning to return to Plum Village to ordain. She thought I was joking. When she realized I was serious, she asked me many questions to test me. Now I realize that I’ve been quite rude to her: I never really told her anything until three months before I left home! I’m her only child and my leaving for monastic life was hard for both of us.

Though my teachers supported me with many opportunities to go to university, I decided not to go. I was afraid I would be caught in some kind of study that would prevent me from discovering who I am. Finally, I left everything behind and decided to come to Plum Village to give it a try.

When did you become an aspirant?

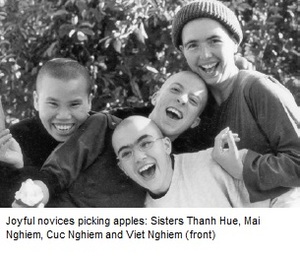

I returned to Plum Village in November 2000 and became an aspirant on my nineteenth birthday. The sisters advised me to wait a year before ordaining as a novice. I shared a room with two other women—both were Vietnamese and old enough to be my mother and grandmother. We didn’t share a common language and I felt a bit lost, at first. The cultural differences were difficult for me to handle, but the practice we shared helped all three of us to get to know and support one other.

What are your days like now that you have ordained?

When there isn’t a retreat, we practice sitting meditation, chanting, and walking meditation every morning. We study basic Buddhism, chanting, and languages. We gather to listen to Dharma talks on Thursdays and Sundays and once a week we have a lazy day.

I’ve become interested in Christianity since I’ve become a nun. I have met Christian monks and nuns and we share our practices. Between us is born a dialogue (which they call communion), in which each one of us expresses the heart of our tradition.

I have so much fun here, in Plum Village. I feel happy, like I’m really blooming, getting to know myself better and at the same time, serving and getting to know others. I like interacting with people, listening to them, helping. For me it’s more important than a formal practice. I received full ordination in November 2004, exactly four years after I arrived in Plum Village to ordain. There is so much for me to learn, I feel I’ll never stop discovering something new!

Every sister has a mentor who is an elder sister in our community, a guide in the practice. My mentor has been a wonderful example of what true patience and listening are, and we share joy and love for life. Our relationship is sometimes sister-to-sister, sometimes mother-to-daughter, and sometimes simply between friends on this path.

Have you stayed in contact with your old friends in Paris?

They think it’s strange that I’ve become a nun. Some of them think I’m crazy. I’m still in touch with a few friends but none of them have come to visit. Most are indifferent to their church and don’t understand what I’m doing here. For them religion is something that changes your thoughts and takes away your freedom. To me, it is the opposite, it is where freedom begins. An inner freedom, the real one!

Lori Zimring De Mori, Integrated Awakening of the Heart, lives with her husband and three children in Tuscany. She is a food and travel writer.