By Kaira Jewel Lingo on

Thầy’s freedom

I am so grateful to have met Thầy and to have been able to spend fifteen years as his monastic student. I first met him when I was twenty-three, and I knew immediately he was the teacher I had been searching for. I have followed him for the last twenty-five years and he has totally changed my life,

By Kaira Jewel Lingo on

Thầy’s freedom

I am so grateful to have met Thầy and to have been able to spend fifteen years as his monastic student. I first met him when I was twenty-three, and I knew immediately he was the teacher I had been searching for. I have followed him for the last twenty-five years and he has totally changed my life, the lives of my family members, and the lives of so many others, offering us a clear path to grow our compassion and wisdom, to experience true happiness and transform our suffering, and to manifest the Buddha nature within us.

When I first learned Thầy had passed away, I paused and breathed. In the stillness, I touched how he was always so free, and that now, having left this body, he could soar like a bird in the sky.

But in his heart, in the ultimate dimension, he was not caught in the form of that practice, not limited in any way by the ritual or ceremony.

Thầy told us a story once that I will never forget. He was sharing about how he practiced at formal lunch, the most formal experience of the whole week in monastery life: the community lines up in the dining hall in silence, in order of ordination, nuns and laywomen before one buffet table, and monks and laymen before another. Monastics hold their alms bowls in a uniform way, and after serving ourselves just the right amount, we walk in procession to the meditation hall, keeping a meter’s distance between the person in front and behind us. We file into the hall and sit down in this same order. We wait till everyone has entered and taken their seat—which can sometimes take thirty minutes—for the whole Sangha to gather, perform the chant and food offering, and then recite the Five Contemplations Before Eating. And before we pick up our bowl to eat, we wait until all of those ordained before us have begun to eat their meal. Everything is very meticulous and also very beautiful in its precision and attention to detail. We eat the entire meal in silence, and once announcements are made and we chant for those who are ill or who have passed away, we stand up and process out in the same order we came in, slowly and ceremoniously. Thầy shared that one day, as he was leading the whole community out of the meditation hall in Upper Hamlet of Plum Village after the meal was finished, in his mind he threw his bowl up into the air and rolled himself in the grass! It was such a surprising image of freedom and playfulness in the midst of something that looked quite somber and serious on the outside. Of course in reality he performed his role, carrying his bowl and leading the hundreds of monastic and lay practitioners out of the hall. But in his heart, in the ultimate dimension, he was not caught in the form of that practice, not limited in any way by the ritual or ceremony. He was completely free. It helped me to see the formal lunch practice in a whole new way, to know how lightly and joyfully he could experience it.

May Thầy’s freedom always guide us and show us the way.

Black is beautiful

I was the first Black monastic in the Plum Village tradition, and it was Thầy’s inclusiveness, especially of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, that helped me see how I could actually live Engaged Buddhism.

I remember when a group of us, including Dharma teacher Larry Ward, approached Thầy in 2003, asking him to teach a retreat for People of Color. Right away Thầy pointed to his own skin and said, “I am also a Person of Color,” and agreed to offer the retreat, which was held at Deer Park Monastery in 2004. We were so happy and amazed when some four hundred people signed up for this first-ever POC retreat in our tradition! Thầy asked me to edit his talks from the POC retreats into a book, and also insisted that both Larry Ward and I, as key organizers of these retreats, have our own chapters in this book, which came out in 2010, titled Together We Are One: Honoring Our Diversity, Celebrating Our Connection.

Another time, as a novice nun in rural southwest France, I wrote a letter to Thầy sharing that I didn’t quite know what to do when I found myself so delighted to see the few other Black people that would come to the monastery. I felt self-conscious about approaching them because they were Black and also worried that my reaction was somehow not equanimous enough. A few days later, Thầy was visiting our nuns’ hamlet and all of us sisters were having tea with him in his room, discussing what color to repaint the meditation hall. He looked straight at me and exclaimed, “Black is beautiful!” We all laughed. It was a powerful and direct teaching of a Zen master, allowing me to break through my self-imposed obstacles and hang-ups and simply love those who were in my presence with freedom and confidence.

Other people are the path

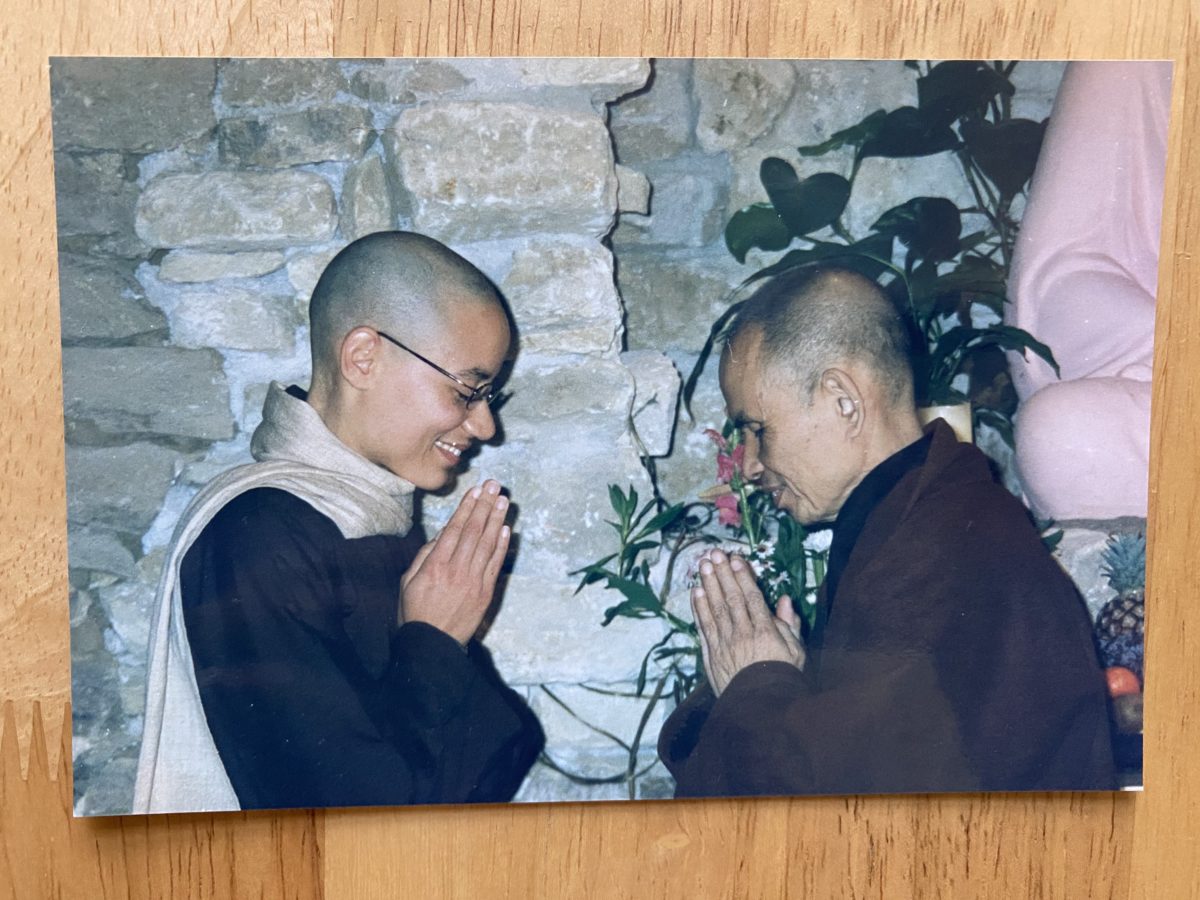

I was fortunate to meet Thầy and the Plum Village Sangha in 1997, when I was twenty-three years old. I received monastic ordination from him in 1999, when I was twenty-five, and he gave me the name True Adornment with Jewel, or Chân Châu Nghiêm in Vietnamese.

...living in community was like washing a bunch of chopsticks after a meal: you rub them up against each other and they clean each other. The abrasion is painful but can also be transformative.

Soon after Thầy and the Sangha ordained me as a novice nun, I began to have difficulties with an elder sister. This sister had gone through a lot of suffering and could sometimes be harsh in her speech with others. This was quite painful for me and I was struggling with the situation as a new member of the monastic community.

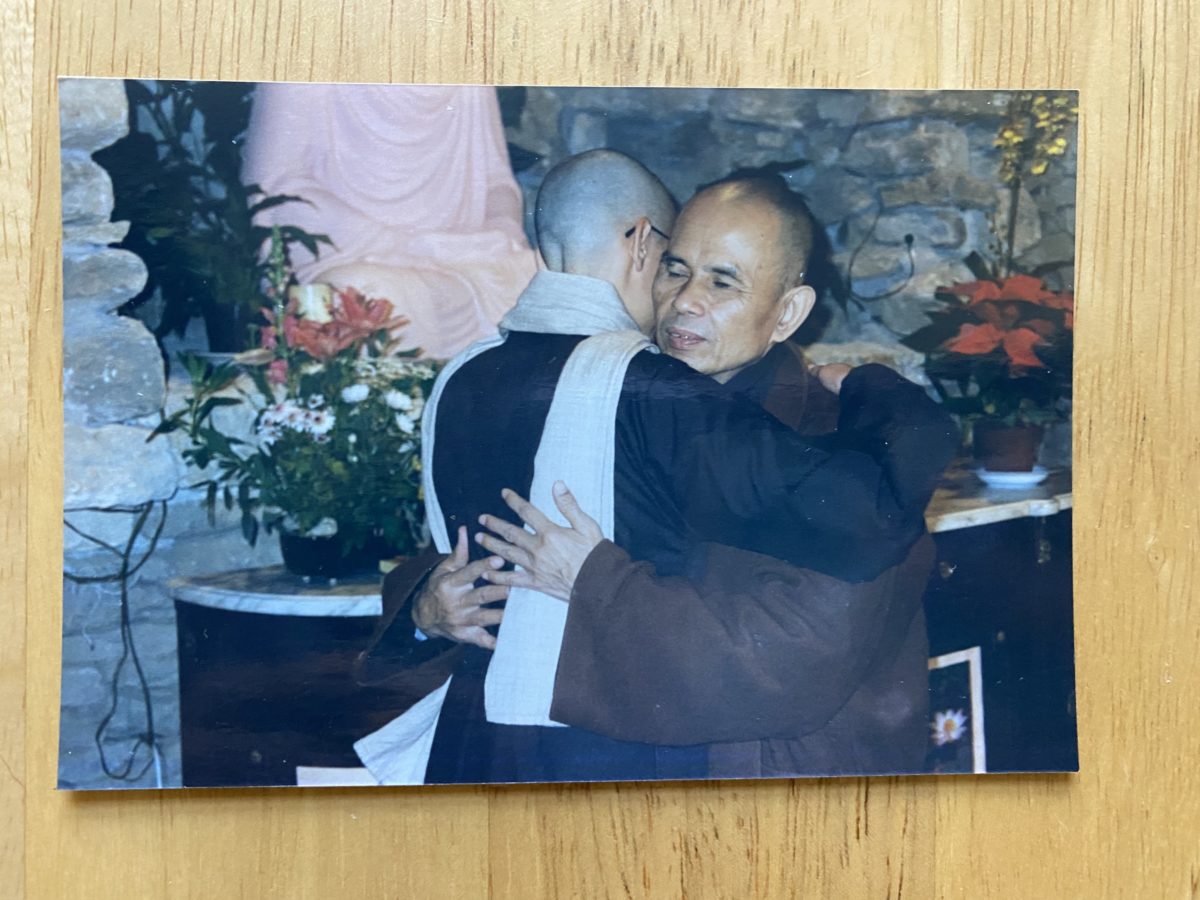

As novices we were fortunate to have the opportunity to be Thầy’s attendants when he would come to teach at our particular hamlet of Plum Village every other week. While Thầy needed very little, it is customary in Asian culture for students to show care for their teacher in this way in order to learn from them more closely. So in pairs we would start by cleaning his room before he arrived, and then spend the day with him, bringing him his meals, preparing his Dharma seat before the talk, inviting guests to his hut, serving him tea, and just being together. It was also, most importantly, a time for Thầy to get to know us and guide us in our practice.

Somehow he knew that I was going through a hard time with a sister. In a quiet moment after lunch, when he was gently swinging in his indoor hammock where he often liked to rest, he looked at me and said softly, “You know, Châu Nghiêm, other people are the path.” He didn’t say much more but I received what he was trying to teach me. The path of awakening does not lead us around or outside of difficult relationships. Our relationships with other people, including and especially the difficult ones, are the very path. They are the conditions that help us to learn to be more free. He had often taught us that living in community was like washing a bunch of chopsticks after a meal: you rub them up against each other and they clean each other. The abrasion is painful but can also be transformative.

His simple teaching was very supportive for me that day and has stayed with me ever since. It is an important reminder that when interactions with others become difficult, learning to work with and reconcile with others is the very purpose of the path.

“Words that inspire self-confidence, joy, and hope”

Thầy’s support came in very practical, empowering ways. Once we were traveling in Thailand and I was very distressed and disappointed in myself, feeling guilty for a mistake I felt I’d made. I went to see him to ask for help, and his attendant was there. Since I didn’t want to share about what was bothering me in front of the attendant, I just sat there and wept quietly. The next day he was to give a presentation at a large international Buddhist conference. On the train ride there he asked if I would help draft speaking points for his talk, which he’d never asked me to do before. Feeling his trust in me and the responsibility he felt I was capable of fulfilling was immediately uplifting and returned my confidence in myself. I recruited another sister and we worked on it together. Touching my bodhicitta in this way balanced out the negative emotions I had been drowning in, thinking I wasn’t good enough or practicing well. Because of Thầy’s compassion and trust, I was able to be much kinder to myself and find my way out of that self-made hell.

Another time, when Thầy was visiting our monastery in Germany, I wrote him a letter and shared how I was suffering because of difficulties I was encountering in my practice. Soon after this, he gave me a letter that a man in the United States had written to him. The man was isolated, depressed, and suicidal. Thầy asked me to reply to this man on his behalf. Reading the letter nourished my compassion and took me out of my own despair and desperation and put me in touch with how much I still had to offer to someone suffering even more than I was. I was again moved by Thầy’s trust and faith in me in the midst of my own lack of faith in my own strength and worthiness. Writing the letter was healing as it touched the seeds of compassion and wisdom in me. In being present for this man’s pain with loving kindness, I was able to care for and work with my own pain as well.

I am so grateful to Thầy for the way he used words and actions to inspire self-confidence, joy, and hope in me time after time. Eventually I was able to generate this from within myself more often and to touch Thầy in me as the source of this wholesome positive regard for myself. What a gift!