Parenting a Child with Special Needs

By Laurel Houghton

We were at home and I went to pick her up. She was blue, and her arms and legs limply dangled between my arms. I thought she was in a deep sleep. Then that she was dead. My first child, three days old. Not yet recovered from giving birth, I called her name,

Parenting a Child with Special Needs

By Laurel Houghton

We were at home and I went to pick her up. She was blue, and her arms and legs limply dangled between my arms. I thought she was in a deep sleep. Then that she was dead. My first child, three days old. Not yet recovered from giving birth, I called her name, trying to bring her back to life as her father sped us to the ER. She’d had the first of many seizures that would only be stopped by literally putting her brain to sleep with drugs.

From that moment on, I lived in fear. I entered into a noble, instinctual struggle to save her life, changing in a few days from a scholarly doctoral student into a ferocious mother tiger. Meditation practice didn’t calm my parental instincts. Despite my ten-year morning and evening meditation practice, as she lay in Intensive Care hooked up to blinking machines and IVs, as she was prodded for blood tests, I lost my solidity. And between the pounding walls of the MRI, holding my tiny baby for a brain scan, I lost my faith.

She survived her birth, but we never found out the cause of the seizures and massive nervous system disorganization. One day she struggled to crawl and then gave up, flopping limply on the living room rug. Our baby was unable to talk, crawl, or walk. Her babble didn’t have normal sounds. It was then that I dropped my doctorate to study speech, occupational, physical, audio, and cutting edge therapies, usually staying up until midnight at our kitchen table as I studied specially ordered texts and planned an intervention program. I refused to accept her bleak prognosis, and solving her disabilities became my full-time work. For me, there was no balance and no breathing. My abdomen became rock hard.

Healthy mothers are often willing to give their life for their child. In my case, my personal determination to change her injured nervous system would dominate my life and become almost lethal. What I didn’t know or understand at the time was that trying to force a huge karmic drama of life into any particular outcome can eventually bring exhaustion and deep despair. Our efforts may be noble, but when we chronically stop breathing as we do our work, we are most likely caught in an ego- and fear-based control over life as it is. And giving my life to save my baby would nearly take both our lives.

My husband tried to help me notice what was good and easy in our family, but I couldn’t hear him. I was too frightened for my child. The already weak marriage became more conflicted and distant. An old family sexual secret that I’d been holding for years was eroding and splitting my psyche even more. Well-meaning friends tried to comfort me with: “God never gives you more than you can bear.” These well-intentioned words can be empty and irritating to a desperate person. What I needed was a powerful voice of wisdom and compassion; I needed to hear the Dharma from a teacher who knew trauma and war and could teach me how to emerge from trauma with clarity and love.

By my daughter’s fourth year, I’d become suicidal. Thoughts of suicide happen when you can no longer bear your life. Not willing to desert my baby daughter, I was feeling more frequent urges to die together with her. I heard the sad news of a Japanese mother in LA who committed suicide by taking herself and her children into the ocean surf with her. Other people were shocked, but I understood deeply. Even when life has become unbearable, a loving mother doesn’t leave her babies behind. Fortunately, years of meditation had strengthened the witnessing part of my mind, and I didn’t follow the despair that I felt. Instead I entered therapy, which brought deep understanding and healing around the roots of suffering in my family of origin.

A Bell of Happiness

In my spiritual practice, there was no one who seemed to speak to my suffering. In the Buddhist community, there seemed to be no one who warmly welcomed children. Then I heard of a monk who had been in war and came out of that violence speaking about flowers being fresh and mountains being solid. It was a faint bell of hope heard by an exhausted, traumatized mother who was struggling with too much and wondering if her child would live.

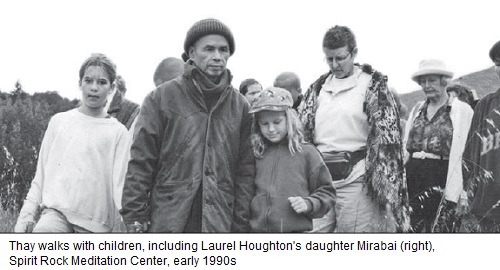

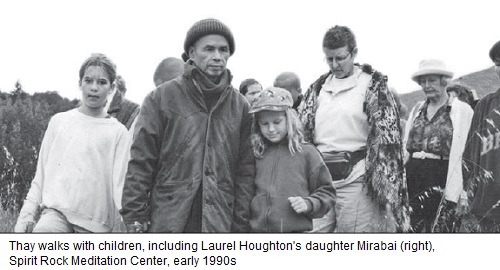

I went to hear Thay with hundreds of other people in the open meadows of Spirit Rock Meditation Center in the early 1990s. Seated beside him on the platform were two beautiful young children. He appeared to inhale their sweet youthfulness. This teacher who came from war, violence, and exile, and who loved children, impressed me. His clear words were an anchor to a quiet place that was deeper than my yelling fears, and a lifeline out of shock and sadness.

It was four years after my daughter’s birth and the cause of her problems was still unknown. The fear in her baby eyes as she fell into another seizure on the porch of our little cottage in San Francisco still flashed in my consciousness. It was as if I were trying to emerge from a bomb shelter. I couldn’t feel any trace of “present moment, wonderful moment.” So I changed it to what I could honestly say: “Present moment, nothing bad is happening right now moment.”

Balancing fear and fatigue with inhaling the present moment, I played Thay’s Dharma talks at home and in the car, and attended every retreat on both U.S. coasts with my daughter in arms. I took her to Plum Village. She would lie in my lap and gaze up into Thay’s quiet and loving face during Dharma talks. She loved the slow, quiet, smiling community, a respite from an impatient culture that moved and talked far too fast for her. And over the years, though we didn’t keep the silence and she ate lots of commercial peanut butter at the retreats, I could feel Thay’s words watering a new consciousness in me.

Present Moment, Not Bad Moment

Then, one year, as I looked at my daughter, a change happened. I was able to honestly shift to a tiny new step and silently say: “Present moment, not bad moment.” It wasn’t a change in her disabilities; it was a change in my consciousness that started to ease the fear and trauma. Noticing the sweet moments of raising a child had started to shift my consciousness like rain streaming into a dried southwest desert creek. Bathing her soft skin in the bathtub with me, I started to notice that the present moment had become an okay moment.

Slow steady changes started to flow within me as I made a powerful intention to live with a persistent practice, and not in fear. I looked at the beauty of camellias when we walked the neighborhood. As my daughter did crawling exercises, I would adore the cuteness of her thick thighs and nibble her tiny toes. While still forcing my growing toddler to make sounds by holding back her carrot juice when she was thirsty, I smiled into her eyes and noticed progress in her flat and incomprehensible sounds. I learned to breathe more deeply as I listened to her various therapists. I worked with the sometimes heartless and bureaucratic schools by walking into her education planning meetings very slowly, breathing, with the soles of my feet touching the earth.

In this mothering practice, I started holding my fearful heart as tenderly as I did my growing child. Eventually, lighter moments of honestly feeling “present moment, wonderful moment” started forming one by one, like deeply lustrous pearls on a strand of our happier life together. It took about seven years of intensive practice to steady myself and diminish the internal drama.

Twelve years ago, for my ordination application, I was asked, “Are you happy?”

I still wasn’t sure. The fears and worries still yipped loudly, like a large pack of coyotes at dusk. But I understood that this barking was the natural, earthly, loving nature of a mother and child. And I’d learned to take good care of the barking worries by simply checking on my daughter’s safety and the multiple to-do lists for her disabilities.

Breathing in Beauty

What is different is this: alongside the fears passing through me are the thoughts of the rosy cherry tomatoes in our organic garden, and the miraculous memory of my daughter dancing a choreography, and now, after many years of parenting, a train adventure in Thailand together. Am I happy? Yes, mostly, I am happy. And it’s possible to still have fear for her. But now, fears don’t sweep me away from the wonderful moment.

Along with holding my daughter’s special needs, I also hold my own heart and fears more gently. I believe that Thay’s presentation of Buddhist teaching and practice was one essential part of literally saving my life from suicide and possibly the life of my baby daughter as well. He taught me to breathe in beauty and balance in the midst of fear and trauma.

My daughter—Mirabai Collamore, Joyful Clarity of the Heart—is part of the first generation of Thay’s American children, having walked hand in hand with him as a little girl and having learned to make a lotus with tiny fingers. Two years ago, at age twenty-two, she chose to take the Five Mindfulness Trainings. The Dharma light shines in her. The disabilities that were so frightening have been chipped away to almost nothing by her hard work. She attends a university where the worries of college studies and exams are held in gratitude as the precious jewels of a normal life. When nervous about her studying, Mirabai listens to her childhood cassettes of Thay, and at night she falls asleep in the arms of his Dharma talks.

As teachers of the Dharma, may we not rush the practice. May we all remember that just the next honest and mindful step, and then the next, and then the next, can gradually walk us out of despair and out of any dark consciousness.

To Thay, dear teacher, my lifelong prostration of deep gratitude.

Laurel Houghton, True Virtue and Harmony, has opened Flowing Waters Retreat at Mt. Shasta, California, a mindfulness practice center, where she hopes to offer a place to alleviate suffering through Dharma practice, the singing crystal pure waters, and the joy of wild spotted orchids growing under the cedars.