By Denise Nguyen

Like many people across the United States, I’ve been inspired by the bravery and eloquence of our young generation in galvanizing our country to fight for sensible gun control laws after the tragic Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting. Trapped in the stereotype that our youths were content to stare at their cellphone screens all day,

By Denise Nguyen

Like many people across the United States, I’ve been inspired by the bravery and eloquence of our young generation in galvanizing our country to fight for sensible gun control laws after the tragic Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting. Trapped in the stereotype that our youths were content to stare at their cellphone screens all day, people were surprised to see such poise and articulation in television interviews and speeches from this generation of teens to the degree that newspapers reported many individuals being convinced the Parkland students were child actors.

The movement started by our young generation made me reflect on our own tradition and how it was built and powered by the mindful hearts and hands of a young Thay and many courageous young Vietnamese adults. Even amidst resistance to modernize Buddhism, they had a deep conviction to practice mindfulness, create a community of brotherhood and sisterhood, and help people with their suffering.

Mindful Action, Mindful Youths, Mindful Community

As a young monk in his twenties, Thay wanted to offer a new kind of Buddhism, one that would help save his country from conflict, division, and war. Along with four other monks, he formed a movement, deeply believing action must be grounded in awareness and mindfulness. The young monks encountered resistance to change from a majority of elders in the Buddhist establishment, who dismissed their ideas and silenced their voices—a similar response we’ve seen from today’s advocates for gun ownership.

Despite confronting these obstacles to their dreams for social justice, Thay and his fellow monks refused to give up hope. Thay turned to community, both monastic and lay, for the support, strength, and energy to continue with his efforts to change society; he created a Buddhist magazine, published books, established the Buddhist Student Union in 1960, and launched the School of Youth for Social Services in 1964. This fourfold Sangha was the first incarnation of our Wake Up movement.

“I was a young Dharma teacher and my students in Saigon were just like my younger brothers and sisters,” Thay recalls in the book Inside the Now. “We shared a common vision and purpose and, even now, whenever I think of them, I still feel so much gratitude—for the love between teacher and student, and for the spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood that we shared. This love has endured, and our intimate friendship has been able to nourish every other kind of love.”

My mother, Kimchi Nguyen, was one of those students then, as was Sister Chan Khong. Thay’s first thirteen students, whom he called “cedars”—evoking the symbolism of strong, hardy trees that would help support the Buddha’s teachings—grew into eighty and then over three hundred cedars who were members of the Buddhist Student Union. This period was a time when the Catholic regime—including then-President Ngo Dinh Diem—oppressed, arrested, and tortured Buddhists.

My mother recalls participating in one of many fasts in Saigon and Hue organized by the monastics and the Buddhist Student Union to protest against the Vietnamese government’s treatment of Buddhists. Thousands of high school and university students—Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike—came together to advocate for religious liberty while practicing nonviolence. The Vietnamese government came after the protestors, searching for them on school campuses. Fleeing to her hometown, my mother stayed with her sister to wait out the raids. She returned to Saigon to continue her studies after the November 1963 coup by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam officers, who disagreed with the Diem regime’s treatment of Buddhists and its handling of the Viet Cong threat.

During this era, the young students endured the deaths of family members and friends and the destruction of villages and other social service projects they helped build with Thay. To navigate such wartime challenges, the students met regularly to share their struggles and bonds, and to provide solace to one another. With the help of Thay’s teachings and their aspiration to practice, they supported one another in handling their strong emotions of despair and anger, while remaining committed to helping the hungry and poor in their country. Because of these acts of courage and the steadfastness of Thay’s young Vietnamese students, the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation felt inspired to name our planned giving program “The Cedar Society,” as a recognition of the legacy and practice tradition the cedars shaped with Thay in Vietnam.

Mini-Tiep Hien

Thay’s connection with young adults and his belief in their ability to effect change continued after Vietnam. We are all familiar with and inspired by the first six Order of Interbeing members, ages 19 to 28, whom Thay ordained in 1966. After settling in France, Thay ordained Anh-Huong Nguyen in 1981 at the age of 19, the first Order member after the original six in Vietnam. She is now a beloved Dharma teacher leading the Mindfulness Practice Center of Fairfax along with her husband, Thu Nguyen, who is also a Dharma teacher.

In 1990, at a time with approximately only forty Order members worldwide, Thay ordained a group of six Vietnamese young adults at Plum Village Monastery: five women and one man, between the ages of 18 and 22. A year after, I joined at 20 years of age as a continuation of the mini-Tiep Hien group, as Thay affectionately called us. At the time some lay elders were opposed to Thay’s action, expressing we were too young and immature to be members. But Thay had always believed in and directly experienced the power of the young generation to be of service. He also knew that in the effort to foster brotherhood and sisterhood and grow Sanghas for young adults, there would be more resonance among them if it was led by their peers—a group of dedicated young mindfulness practitioners with a strong volition to practice and be of service.

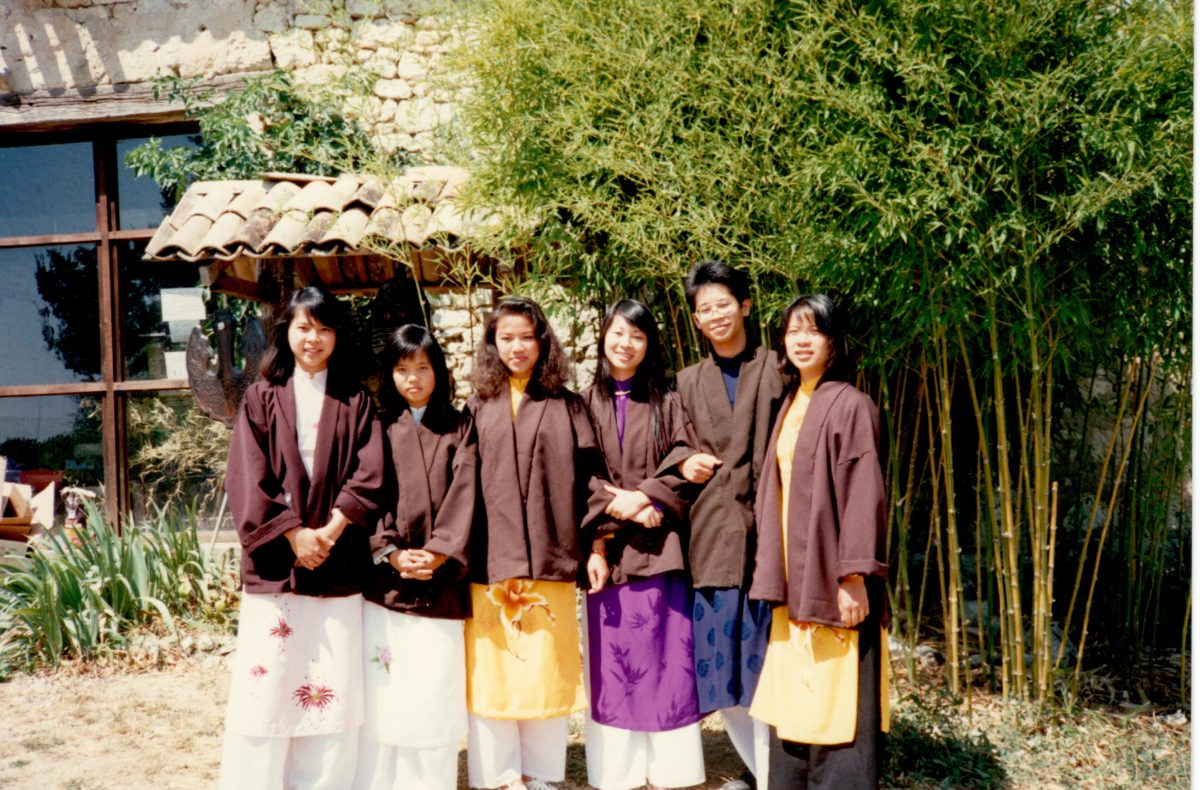

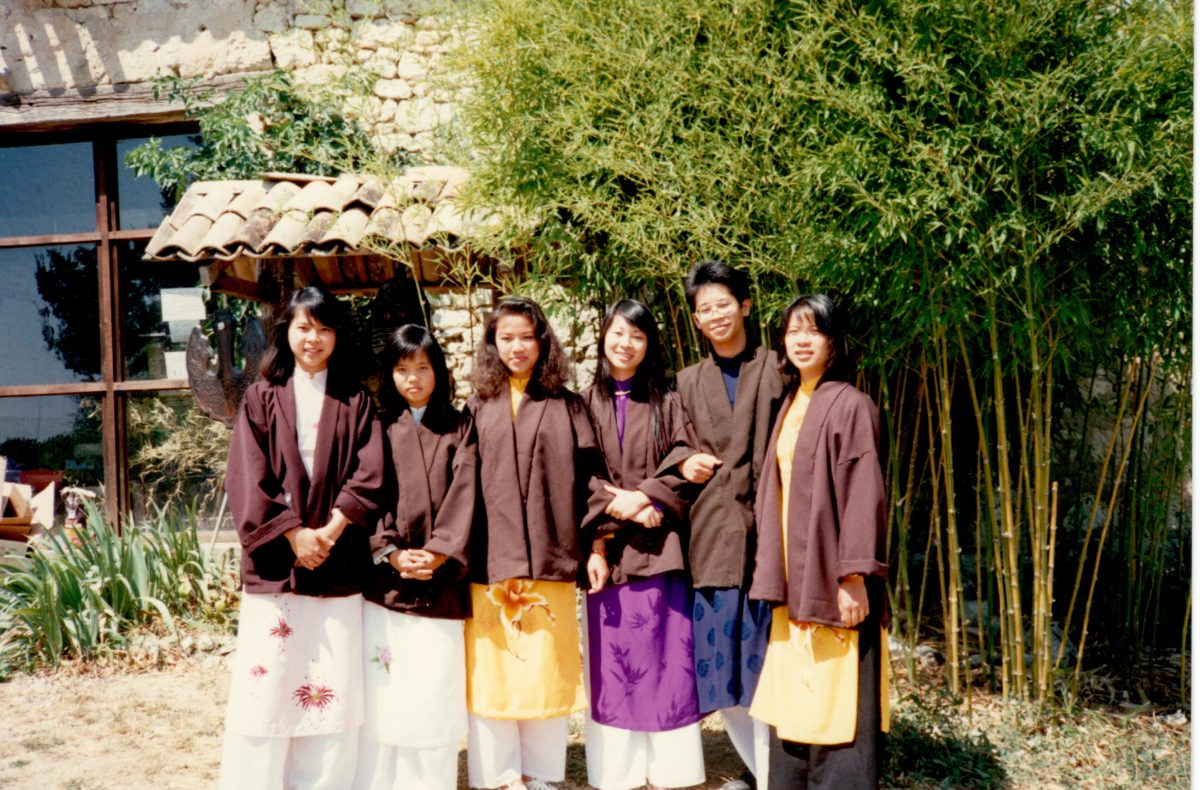

Hence began the second wave of “Wake Uppers” into our tradition. And lead we did. I remember that in the midst of studying for college midterms, I developed the schedule and assignments for a retreat with Thay at Camp Seely, California, in 1993. As a grade-school teacher, one other mini-Tiep Hien member, Annie Mai Bevacqua, brought a bell into her class and taught her students how to breathe, in an era when mindfulness was not in mainstream society’s consciousness, and Wake Up Schools did not exist yet. When I look at an old photo of our young adult Sangha as we practiced inviting the bell in preparation for a Day of Mindfulness we organized for Sister Chan Duc (Sister Annabel) and Sister Chan Dieu Nghiem (Sister Jina), I can see how much joy, fun, and togetherness we shared. And true to Thay’s foresight, we found comfort during Dharma discussions when we shared with one another our happiness and challenges at that similar stage of our lives.

Wake Up: The Third Wave

Thanks to Wake Up, the number of young adults deeply practicing in Thay’s tradition grows every year. It is a thriving, international movement with one hundred Sanghas continuing the rich history of Engaged Buddhism shown by the first generation of Wake Uppers in Vietnam; that is now combined with the dedication to Sangha building started by the second wave. In 2017, a group of nine Wake Up members—funded by donations to the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation—traveled to Tijuana, Mexico, to lead a public talk, a session with therapists, and an event with students. Attendees to these events shared how they were inspired to start their own Sanghas in Tijuana after feeling embraced by the practice and witnessing the bond, respect, and camaraderie the Wake Up members had with one another.

As Phuong Thao Le Dong, one of Thay’s original cedars, said to me, there is a strong confidence and trust amongst her generation in the young adults to continue what Thay started in Vietnam. As a member of the second wave of young adults, I also have a great sense of happiness knowing our global beloved community continues to support and develop our next generation of young Thays and cedars. Like Thay, I believe in the young generation to lead us and continue our rich history and practice.

Denise Nguyen, True Moon Lamp, is the Executive Director of the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation. She lives in Los Angeles, California, with her beloved dog Bodhi.