By Thich Nhat Hanh in June 2019

Deer Park Monastery

August 22, 2001

You have to organize your daily life so that it will express the Fourth Noble Truth: showing the path, teaching the living Dharma with your own life.

There is a lot of Dharma talk in the air,

By Thich Nhat Hanh in June 2019

Deer Park Monastery

August 22, 2001

You have to organize your daily life so that it will express the Fourth Noble Truth: showing the path, teaching the living Dharma with your own life.

There is a lot of Dharma talk in the air, and there is a lot of air in the Dharma talk. Today is the 22nd of August 2001 in the Deer Park Monastery.

There is a sutra with the title Yasoja—that’s the name of a monk, the Sangha leader. This sutra is found in the collection called Udāna, Inspired Sayings.

Yasoja was a Sangha leader of a community of about five hundred monks. One day he led the monks to the place where the Buddha lived, hoping they could join the three-month retreat with the Buddha. Ten days before the retreat began, they arrived very joyfully, anticipating seeing the Buddha and all the other monks. There were a lot of greetings, a lot of talking, and from his hut the Buddha heard a great noise.

He asked Ananda, “What is that noise? It sounds like fishermen landing a catch of fish.”

Ananda told him the Venerable Yasoja had arrived with five hundred monks and they were all talking with the resident monks.

The Buddha said, “Ask them to come.”

When the monks came, they touched the earth before the Buddha and sat down. The Buddha said, “You go away, you cannot stay with me. You are too noisy. I dismiss you.”

So the five hundred monks touched the earth, walked around the Buddha, and left the monastery of Jeta Park. They went to the kingdom of Vajji, on the east side of Kosala, which took them many days to reach. When they arrived on the bank of the River Vaggamuda, they built small huts, sat down, and began the Rain Retreat.

During the ceremony opening the retreat, Venerable Yasoja said, “The Buddha sent us away out of compassion. You should know that he is expecting us to practice deeply, successfully. That is why he sent us away. It was an expression of his deep love.”

All the monks were able to see that. They agreed that they should practice very seriously during the Rain Retreat to show the Buddha that they were worthy to be his disciples. So they dwelled very deeply, very ardently, very solidly. After only three months of retreat, the majority of them had realized the three enlightenments, the three kinds of achievement. The first is about remembering all their past lives. The second is to realize the truth of impermanence, to see clearly how the lives of all beings come and after a time they go. The third realization is that they have ended the basic afflictions in themselves: craving, anger, and ignorance.

One day after the Rain Retreat, the Buddha told Ananda, “When I looked into the east I noticed some energy of light, of goodness. And when I used my concentration, I saw that the five hundred monks that I sent away have achieved something quite deep.”

Ananda said, “That is true, Lord, I have heard about them. Having been dismissed by the Buddha, they sat down in the Vajji territory and began serious practice, and they all have realized the three realizations.”

Buddha said, “That’s good. Why don’t we invite them to come over for a visit?”

Teacher-Disciple Relationship

When the five hundred monks heard the invitation of the Buddha, they were very happy to visit him. After many days of traveling, they came at about seven o’clock in the evening and they saw the Buddha sitting quietly, in a state of concentration called imperturbability. In this state you are not perturbed by anything; you are very free, very solid. Nothing can shake you, including fame, craving, hatred, or even hope.

When the monks realized that the Buddha was in the state of imperturbability, they said, “The Lord is sitting in that state of being, so why don’t we sit like him?”

So they all sat down, very beautifully, very deeply, very solidly. All of them penetrated the state of imperturbability and sat like Buddha. They sat for a long time.

When the night had advanced and the first watch had finished, the Venerable Ananda came to the Lord, knelt down, and said, “Lord, it is already very late in the night. Why don’t you address the monks?”

The Lord did not say anything. They continued to sit until the second watch of the night had gone by. About two or three o’clock in the morning, Ananda came, knelt down, and said, “Lord, the night has gone very far. It is now the end of the second watch. Please address the five hundred monks.”

But the Buddha kept silent and continued to sit. All the monks continued to sit also.

Finally, the third watch of the night was over, and the sun began to appear on the horizon. Ananda came for the third time, and kneeling in front of the Buddha said, “Great Teacher, now that the night is over, why don’t you address the monks?”

The Buddha opened his eyes and looked at Ananda. He said, “Ananda, you did not know what was going on and that is why you have come and asked me three times. I was sitting in a state of imperturbability, and all the monks also sat in that state of being, not disturbed by anything at all. We don’t need any greetings. We don’t need any talk. This is the most beautiful thing that can happen between teacher and student. We just sit, dwelling in a state of peace and solidity and freedom.”

I find that sutra very, very beautiful. The communication between teacher and disciple is perfect. A student should expect nothing less than the freedom of the teacher. The teacher should be free from craving, free from fear, free from despair. When you come to the temple you should not expect from your teacher anything less than that. You should not expect small things, like having a cup of tea with the teacher or having him praise you. These kinds of things are nothing at all.

You should expect much more than that. If your teacher has enough freedom, enough peace, enough insight, then that will satisfy you entirely. If he does not have any solidity, any freedom, then you should not accept him or her as your teacher because you’ll get nothing from him or her.

What do you expect from a Dharma teacher or a big brother or sister in the Dharma? What do you expect from your students? You should not expect small things. You should not expect him or her to bring you a cup of tea, a good meal, a cake, some words of praise. These things are nothing at all. You should expect from your students their transformation, their healing, their freedom.

When teacher and students are like that, they are in a state of perfect communication. They don’t have to say anything to each other. They don’t have to do much. They just sit with each other in a state of solidity and imperturbability. That is the most beautiful thing concerning a teacher-student relationship.

I find this sutra very, very beautiful.

When a student practices well, he or she can see the teacher in himself, in herself. And when a teacher practices well, he can see himself in the student. They should not expect less than that. If you always see the teacher as someone outside of you, you have not profited much from your teacher. You have to begin to see that your teacher is in you in every moment. If you fail to see that, your practice has not gone well at all. And as the teacher, if you don’t see yourself in the students, your teaching has not gone very far.

True Transmission

When I look into a person, a disciple, whether she is a monastic or a lay person, I would like to see in her that my teaching has only one aim: to transmit my insight, my freedom, my joy to my disciples. If I look at him and I see these elements in his eyes, I am very glad. I feel that I have done well in transmitting the best that is in me. Looking at his way of walking, of smiling, of greeting, of moving about, I can see whether my teaching has been fruitful or not. That is what is called “transmission.”

Transmission isn’t organized by a ceremony with a lot of incense and chanting. Transmission is done every day in a very simple way. If the teacher-student relationship is good, then transmission is realized in every moment of our daily life. You don’t feel far away from your teacher. You feel that he or she is always with you because the teacher outside has become the teacher inside. You know how to look with the eyes of your teacher. You know how to walk with the feet of your teacher. Your teacher has never been away from you. This is not something abstract; we can see this ourselves. When you look at a monk or a nun or a lay disciple and you see Thay in him, you know that he is a real disciple of Thay. And if you don’t see that, you might say that this is a newly arrived person, he has not got any Thay within himself. That is seen very clearly.

When we look into ourselves, we can see whether our way of walking or smiling or thinking has that element of freedom, of joy, of compassion. If we see it, then we know that Thay has been taken into ourselves; we are a true continuation of our teacher. You don’t need another person to tell you; you can see it for yourself. And when you look at your fellow students, you can see it as well, if the teacher-student relationship is good. If it is good, that transmission is being done in every moment of our daily life.

Every time we take a step, we know for ourselves whether that step has the content of peace, joy, solidity, or not. You don’t need your teacher to tell you. You know whether your step is a real step, containing solidity and freedom. If your step does not have freedom, you know it doesn’t. If your step does not have the element of solidity, you know it doesn’t. It’s not hard; it’s so obvious.

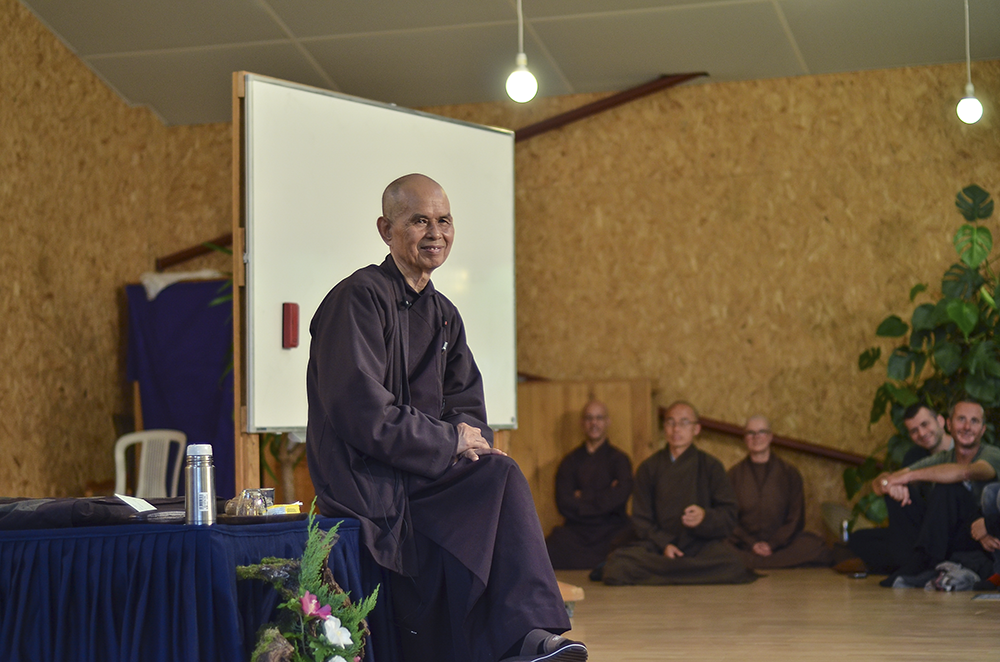

[Thay holds up an empty glass.]

Your step is like the glass. It can be empty and then maybe some juice or some tea goes in.

[He pours tea into the glass.]

If there is some tea in the cup, it is obvious. With the tea in the cup, you can drink and enjoy it.

[Thay sips the tea. He draws a row of circles indicating steps on the whiteboard.]

Suppose I make a step here, a step here, a step here. My practice is to fill each step with the elements of solidity and peace, because I know that each step like that is highly nourishing and healing. When I make a step, I say, “I have arrived, I am home.” There is the element of arrival here, and you know whether you have arrived or not.

We have been running all our lives. We do not know how to enjoy every step we make. Now that we have become a student of the Buddha, we want to make real steps. Every step should be full of the element of arrival, full of the element of here and now, full of the elements of stability, solidity, and freedom.

In the time of the Buddha, there were no airplanes, there were no buses, there were no cars. The Sangha just walked from one country to another. They spent time in many countries, and yet they only walked. With their way of walking, they were able to enjoy every step. The Buddha was a monk, and many of his disciples were monks. They were traveling monks, walking from one place to another. They only stopped traveling during the three-month retreat, so they had plenty of chances to practice walking meditation. Wherever they went, they inspired people because of their way of walking and sitting.

Walking is a kind of sitting. You can arrive fully when you walk, just like when you sit. You are not in a hurry; you are not looking for something outside yourself. You know that everything you are looking for is in the here and the now. That is why every step you make helps you to arrive in the here and now. That is why the teaching and the practice of arrival is so wonderful, so marvelous.

Our society is characterized by running. Everyone is running to the future. You want to assure a good future, and since you see other people around you running, you cannot resist running too. We do not have peace; we are not capable of being in the here and the now and touching life deeply. Running like that, we hope to arrive. But running has become a habit, and we are not able to arrive any more. Our whole life is for running.

In this teaching and in this practice, the point of arrival is not somewhere else. The point of arrival is in every minute, in every second. Life is like that. Life is a kind of walk. [Thay taps each circle on the board.] Life can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, making a step. Here, here, here. We continue like this. So life can be found in a step and in the space between steps. If we expect to see life outside of these steps and the space between steps, we don’t have life. The great majority of people are running, and that is why the practice of arrival is so important. It’s a drastic kind of medicine to heal our society and ourselves, because we carry, in each of us, the whole of society. The whole of society is running, and therefore we are running. So awakening can bring the desire to resist, to stop.

The Three Doors of Liberation

The teaching of the three doors of liberation is crucial. The door of emptiness, the door of signlessness, and the door of aimlessness. Aimlessness means that you are not running anymore because what you want to become you already are. What you are searching for is already there in the here and the now.

Your peace, your happiness, your solidity, your freedom is available in every step. Aimlessness means you should stop, you should not run any more. If you think of getting peace and freedom, peace and freedom are right here, right now. The belief that peace and freedom are somewhere else is an error. That is why every step you take should be able to bring you to the place where freedom and solidity exist. Freedom and solidity are the grounds of true happiness. Without solidity, no happiness is possible; without freedom, no happiness is possible. That’s why every step can generate stability, solidity. Every step can generate the energy of freedom. If you practice walking correctly, then the energy of freedom and solidity can be generated in every step. Happiness is right there, in every step.

Another person watching you walk is able to see whether your steps have the elements of solidity and freedom. But you don’t need him to tell you; you know very well whether the step you take has the elements of solidity and freedom. You are walking but you have already arrived with every step, and walking like that is your daily practice. Arrival is achieved in every step. It would be nice to send Thay a postcard with the inscription, “Thay, I have arrived.” It will make him happy. “I have arrived, I don’t run anymore.”

The habit of running has become very strong. It is a collective habit, a collective energy. Mentally, you find it normal to run. But it’s not normal, because if you continue to run like that, happiness will not be possible, peace will not be possible. We participate in creating suffering, both collective suffering and individual suffering, when we are constantly running. That is why it is very important to learn how to stop.

Freedom from Afflictions

The Buddha and his monks did not have a lot to consume. They did not have a bank account. They did not own big buildings and houses. Each monk was supposed to have only three robes, one begging bowl, and one water filter, which they carried with them. The monks and the nuns of our time try their best to follow this example.

If you want to become a monk or a nun, you should know that a monk or nun should not have a personal bank account. No one in the Deer Park has a personal bank account. No one has a personal car. Even the robes we wear do not belong to us—they belong to the Sangha.

If you need a robe, your Sangha will provide you with one, but that does not mean that it becomes your robe. It remains a robe of the Sangha. Even your body is not your personal property. When you become a monk or a nun, your body doesn’t belong to you as personal property. You have to take care of your body because it is part of the Sangha body. Other monks and nuns have to help take care of your body, and you have to allow them to take care of you. They can intervene in the way you eat and drink, because your body does not belong to you, it belongs to the whole Sangha—the Sangha body, Sanghakaya. You don’t own anything at all, including your body, and yet happiness is possible, freedom is possible. Happiness and freedom are easier if you don’t own many things. Usually if you don’t own anything you are very afraid, you don’t feel any security. But the practice of a monastic goes in the opposite direction. What guarantees your well-being is not possessions, but the giving away of all possessions.

I remember when Sister Thuc Nghiem, Sister Susan, became a nun, along with others. They took everything from their pockets and they gave it to Thay, everything from coins worth thirty-five cents to the key to their car. They gave everything to Thay. To become a nun or a monk, you should give up everything. You have to donate everything before you can be accepted as an ordained novice. You are advised not to donate it to the temple where you are going to become a monk or a nun. You have to donate it to some other organization, not the temple you accept as your home.

One day Thay gave an exercise to all the monks and nuns: “Tell me of your daily happiness. List your daily happiness on a piece of paper.” Many of them filled up more than two pages. Among the things Sister Susan wrote down was, “My happiness is that I do not have any money anymore, even one cent.” That is true. Before she became a nun, she had a very big sum of money, but she did not have peace. She did not have happiness. But after becoming penniless, she got a lot of liberty, a lot of freedom, and that is the foundation of happiness. That is why she wrote down, “My happiness is that I do not have any money anymore.” That is what she really felt.

Many people believe that practicing as a monk is the hardest, but that is not the case. It is easy to practice as a monk or a nun. You have entrusted yourself entirely to the Sangha. You don’t have to worry about anything: food, shelter, medicine, transportation. Everyone around you is practicing. Everyone is practicing walking mindfully, enjoying every step, so it would be strange if you didn’t do the same. You are naturally transported by the boat of the Sangha. Even if you don’t want to, you go anyway, in the direction of peace and freedom! You have left behind your family—your father, your mother, your friends, your job—to become a monk or a nun. Your purpose is to be free because you know that true happiness is not possible without freedom. You aspire deeply to freedom, and freedom here means freedom from afflictions.

Of course, political freedom is enjoyable, but if you are not free from your afflictions, then political freedom does not mean anything. You are a refugee and do not have that piece of paper that allows you to go anywhere you want. The deepest desire of people is to have a piece of paper called an identity card or passport. There are those of us who waited ten, twenty, thirty years, and still didn’t get that piece of paper. They believe that when they get that piece of paper they can become free, and they can go anywhere they want. But there are also those of us who have that passport, that piece of paper, but don’t feel any happiness, and many even committed suicide.

Political freedom is enjoyable, but if you are not free from your afflictions—namely craving, despair, jealousy—suffering is still there within you and around you. That is why the purpose of the practice is to get free, so the Kingdom of God is available to you, so true life is possible to you in the here and the now.

We have the impression, very clear sometimes, that the Kingdom of God, the Pure Land of the Buddha and all its marvels are very close. In fact, everything in us and around us is a miracle. Your eyes are a miracle, your heart is a miracle, your body is a miracle, the orange you are eating is a miracle, the cloud floating in the sky is a miracle. If they do not belong to the Kingdom of God, then to what do they belong? In our busy lives we sometimes have the clear impression that the Kingdom is there, available, but since we are running all the time, thinking we do not have freedom, we cannot get into it; it is not available to us.

I always say the Kingdom of God is available to you, but you are not available to the Kingdom. That is why we learn to breathe and to walk in such a way that we become a free person. That is the meaning of all the practice.

To practice is not to become a Dharma teacher. A Dharma teacher is nothing at all. It does not mean to become a Sangha leader. A Sangha leader does not mean anything at all. What is the use of being the head of a big temple if you continue to suffer deeply? The purpose of practice is to become free, and with your freedom, happiness is possible. When you have freedom and happiness, you can help so many people. You have something to share, you have something to offer to them.

You don’t share your ideas. You don’t share what you have accumulated from your Buddhist studies, because even professors of Buddhist studies may suffer deeply if their Buddhist studies haven’t helped them. Buddhist studies may be helpful, but what you need is not really Buddhist studies; what you need is freedom.

So our happiness is the accumulation of peace. What we study, the authority we get in the Sangha or in society, the fame we get, all are things that people are looking for in society; many of them get plenty of these things, but they aren’t truly happy. Many of them commit suicide. Our way should be different. Our way is the way of freedom.

Is it possible to be free? Looking into the person of a practitioner, whether that is a Dharma brother, a Dharma sister, or your teacher, you can see how much freedom and happiness she has. You would like to have true Dharma brothers and sisters. Sitting close to them and living close to them, you profit from their happiness and freedom, because their happiness is based on their freedom and not on anything else, like fame, authority, or power. What we profit from in a Sangha is the opportunity to do what the other people are doing—namely sitting, walking, smiling, breathing. In arriving, all are having freedom.

The Brown Jacket: An Opportunity to Practice

What is the meaning of wearing a brown jacket? It is not to say that I am an ordained member of the Order. That’s nothing. It’s like the value of a student identity card. You got into a famous university, and it’s given you an identity card. But if you don’t study, what is the use of having the identity card? Having the ID is so you can make use of the library, go to classes, and have professors. It means to study. So when you get the ordination, when you receive the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings, when you get a jacket, that is the identity card, and that allows us to profit from the Sangha, from the teaching, from the practice.

There are Dharma centers, there are monasteries, there are teachers, there are Dharma brothers and sisters who practice. Our being a member of the OI helps us to profit from all these things in order to advance on our path of freedom. As we have freedom, we can begin to make people around us happy. We know that practicing without a Sangha is difficult. That is why we try our best to set up a Sangha where we live. To be an OI member is wonderful. To be a Dharma teacher is wonderful—not because we have the title of OI membership or the title of Dharma teacher, but because we have a chance to practice.

As an OI member, you have to organize the practice. Wherever you are, it’s your duty to set up a group of people practicing; otherwise it does not mean anything to be an OI member. An OI member is expected to organize the practice in her or his area—a group of five people, six people, ten people, twenty people—and to practice reliably on a local level and sometimes on a national level. So the advantage is that having a Sangha, you have to take care of the Sangha, and the Sangha is what supports you in your practice. Thanks to the Sangha, you have to practice. The Sangha is to support you in your practice. So building the Sangha means building yourself. If the Sangha is there, you practice with the Sangha. So a Sangha builder can benefit. She has an opportunity to practice.

Being a Dharma teacher is also an opportunity, because as you teach, you cannot not practice! As you teach, you have to practice in order for your teaching to have content. How can you open your mouth and give a teaching if you don’t do it? Teaching is an opportunity. Even if you are not an excellent teacher yet, being a Dharma teacher helps very much, because when you open your mouth and begin to share the Dharma, you have to practice what you are sharing. Otherwise it would look strange. It’s like a monk living with other monks, all doing walking meditation; it would look strange if that monk did not practice. Being a Sangha builder, you get the opportunity to practice; being a Dharma teacher, you get the opportunity to practice.

Every member of the Sangha can be a favorable condition to you, whether that member is good in the practice or not so good in the practice. Each inspires you to practice. So being a Sangha builder, being an OI member, being a Dharma teacher, is a very good thing, if you know what it means.

It would be strange if we got the precepts, the transmission, and got a jacket, but we don’t have a Sangha to practice with. It would be exactly like getting a student ID and not going to the library or to the classes. You say, “You know, I’m a student of that famous university!” Very strange. So Sangha-building is what we do, and Sangha-building is the practice. Sangha-building means to help each element of the Sangha to practice. You are like a gardener; you take care of every member of the Sangha. There are members who are so easy to be with and to deal with, and there are members who are so difficult to be with and to deal with. And yet, as a Sangha builder, you have to help everyone. There are members of the Sangha you can enjoy deeply. They’re so pleasant to be with. There are other members of the Sangha with whom you have to be very patient.

Please don’t believe that every monastic or layperson in Plum Village is equally easy for Thay! That’s not the case. There are monastics who are very easy to be with and to help, but there are monastics who are so difficult. As a teacher, you may have to spend more time and energy with those who are so difficult. You may want to say no to these elements, but you need to surrender. You cannot grow into a good practitioner, you cannot grow into a good Dharma teacher, if you only want the easy things.

In a Sangha, it is normal to have difficult people. These difficult people are a good thing for you. They will test your capacity of Sangha building and practicing. One day you’ll be able to smile and you won’t suffer at all when that person says something not very nice to you. Your compassion has been born, and you are capable of embracing him or her within your compassion and your understanding. And you know that your practice has grown. You should be delighted when you see that what they say or do does not make you angry or upset anymore, because you have developed enough compassion and understanding. That is why we should not be tempted to eliminate the elements we think to be difficult in our Sangha.

Sangha building needs a lot of love and compassion. If you know how to handle difficult moments, you will grow as a Sangha builder, as a Dharma teacher. Thay is speaking to you out of his experience. He now has a lot more patience and compassion. His happiness has grown much greater because he has more patience and compassion. You should believe Thay in these respects. We suffer because our understanding and compassion aren’t large enough to embrace difficult people. But with the practice, your heart will grow; your understanding and compassion will grow, and you will not suffer any more. You have a lot of space, and you can give them space and time to transform. Thanks to the Sangha practicing, thanks to your model of practice, they will grow, they will transform. The transformation of difficult people is a greater success than for only pleasant, easy people.

Love is not only enjoyment. We enjoy the presence of pleasant people, lovely people, but love is not just that. Love is a practice. Love is the practice of generating more understanding and compassion. That practice generates true love. Please always remember that love is not just a matter of enjoyment. Love is a practice. And it is that aspect of love that can bring you growth and happiness, the greatest happiness.

There is no way to happiness; happiness is the way. Remember! Happiness and success should be found in every moment of your daily life and not at the end of the road. The end of the road is the stopping. Life is now, in every minute, every second. Happiness, joy, peace should be every moment. Peace is every step. Happiness is every step. It’s so clear, it’s so plain, it’s so simple.

Four Levels of Sangha Practice

[Thay writes on the board.]

Suppose I draw a circle representing my root Sangha where I have gotten my ordination in the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings, where I have gotten a teacher and many Dharma brothers and sisters. I’m born from that place. The root Sangha is my spiritual birthplace, and every time I think of it I should feel joy, pure joy, and hope. That is a lovely place, that is my birthplace. I have so many brothers and sisters living there. I have many teachers living there. When I think of it I feel inspired, I feel happiness. All of us should have such a place, and we carry that place with us everywhere we go. That place is situated not just in space; it is within us. Those of us who do not carry such a place in our hearts do not have enough happiness. It’s a pleasure to go back to the root Sangha and to be there. I have my function, my role in society, but I hold my root Sangha within my heart, a source of inspiration, a source of energy for me, and around me I build a local Sangha.

I’m aware that although it is my local Sangha, it will be the root Sangha of many other people. Whether it is in Chicago, in Buffalo, in Montreal, my local Sangha will become the root Sangha for friends who come. So the root Sangha is not out there; the seed of the root Sangha in me will help make this local Sangha into a root Sangha. I am a member of the OI. I have to make it into the home of several of my friends who constitute my Sangha here. And my Sangha here reflects the image of the root Sangha there.

In my Sangha, people know how to enjoy every step, every breath. They know how to take care of each other. They know that the purpose of the practice is to get freedom and nothing else. I build my Sangha out of love, out of my deepest desire. That is the path I undertake, the path of freedom. I devote my time, my energy into building a Sangha of brotherhood. If brotherhood is not there, happiness is not possible. The mark of an authentic Sangha is brotherhood, of those who come to the Sangha because they want to have brothers and sisters in the practice of freedom. If the practice is correct, then brotherhood will grow and will sustain us. Even in difficult moments, brotherhood is always there to sustain us, to help us stand firm in our practice.

We know that nearby there is another local Sangha, with an OI member who is doing exactly what we are doing. So weekly, we practice with our local Sangha. We organize local events such as Days of Mindfulness, short retreats, Dharma discussions, tea meditation, and walking meditation. From time to time we invite other local Sanghas to join us and create a regional activity. We combine our talents and our experience with other OI members and Sangha builders to create the regional event. Everyone can contribute, and everyone can learn a lot from activities on the regional level.

Then from time to time we organize activities on a national level. You might organize at a Dharma center like Deer Park or Blue Cliff to hold national activities. And finally, there will be activities on an international level, where we meet with practitioners from all over the world. Together we share our practice and learn from one another.

So there are four levels of practice: local, regional, national, and international. Happiness should be possible on the local level, in our daily practice.

The Living Dharma

We recognize the suffering that is going on around us and inside of us. Our practice is not to get away from our real problems, our real difficulties, our real suffering. The practice, according to the path shown by the Buddha, is to recognize suffering as it is, to call it by its true name, and to practice in such a way that we can identify the deep causes of suffering. The division in families, the violence in school and in society—all these things have to be confronted directly with our mindfulness in order for us to see deeply the nature of suffering, of how the suffering has been made.

Ill-being, that is the First Noble Truth. The Second Noble Truth is the making of ill-being. This understanding of the making of ill-being should be very clear. We have to consider every cause that has led to suffering, such as alcoholism and drugs, AIDS, violence, the coming apart of families. We have to look deeply into the nature of ill-being to see their causes. We have to call these by their true names.

Understanding the nature of suffering is the practice, the Second Noble Truth. When understanding of the Second Noble Truth is deep, then naturally the path will emerge: the Fourth Noble Truth, the cessation of ill-being. It means the birth of well-being—it’s the same, the path leading to the cessation of ill-being. So with the understanding of the nature of ill-being, the path leading to the cessation of ill-being becomes apparent. The Third Truth is just the cessation of ill-being.

The Fourth Noble Truth is the path leading to the cessation of ill-being. It has been repeated and repeated that once the Second Noble Truth is understood, then the Fourth Noble Truth will reveal itself. That is the true Dharma. The true Dharma should be embodied by the practitioner, by the Sangha leader, by the OI member. You have to organize your daily life so that it will express the Fourth Noble Truth: showing the path, teaching the living Dharma with your own life.

It is great happiness when someone in the Sangha embodies the living Dharma. Your Sangha may be five people, ten people, twenty people, fifty people. If there is one of you who embodies the path, the living Dharma, that’s wonderful. And everyone can look to him or her as a model for practice. Very soon the Sangha will carry the Dharma within herself. The Sangha will embody the Dharma. That is when the Sangha becomes the most convincing element, because it is a true Sangha, a living Sangha. The Buddha and the Dharma are contained in it, because a true Sangha always carries within herself the true Buddha and the true Dharma.

If you are a Sangha builder, be sure that in your Sangha there are those who can embody the living Dharma. They live in such a way that makes the Dharma apparent—the Dharma not only in cassette tapes, books, and Dharma talks, but the Dharma in the way you live your daily life.

Training OI members does not mean to acquire a lot of Buddhist studies, although Buddhist studies are very helpful. But we want something more. When Sister Annabel offers training for OI members, she doesn’t just offer Dharma talks. Everyone participates in walking, in sitting, and in other practices. This method presents more than a set of theories; it presents the living Dharma.

After having practiced for one year, a person might like to ask for ordination and become a member of the core community. But if during that period, she or he has had no chance to train, then the ordination ceremony is not possible, because the ordination ceremony is offered based on the training and not on the desire of someone to become a member of the core community alone. The desire is good, but it’s not enough; there needs to be training. If you are a member of the core community, it is your task to train people in your local Sangha so that they know the practice, what is the true Dharma, and how to apply the Dharma in their family life, in the workplace, in social life. The Dharma should be their way of life, the art of mindful living.

Many of you may come together to discuss how to organize a regional event of seven to ten days, so OI members and aspirants for ordination can be trained. You might ask two or three sisters from the root Sangha to come and help you, or you might ask a lay Dharma teacher.

Of course, on the national level the root Sangha will be involved. There should be documents and materials for training. But the training should be done in concrete terms, so that transformation and healing is possible. In six-day retreats, we see a lot of people transform, like the one we had at the University of Massachusetts. Eight hundred and fifty people came for a retreat of six days. The quality of the retreat was very high, and people enjoyed it so much. Many reports of transformation came each day. Reconciliation was made among members of families, even with people who were not present, through telephone calls. If you have been in a retreat, you know that the presence of those of us who have a solid practice is very helpful to retreatants.

In the retreat at the University of Massachusetts we had seventy monastics, many OI members, and many experienced practitioners. There were so many new people who had just read books and came to a retreat for the first time. They arrived and joined the practitioners very naturally, like a small stream of water joining a big river. The sisters and brothers who attended the retreat shared many stories of transformation. That made us very happy, because the retreat helped so many people, including many young people.

I remember one day I invited all the children to sit on my right, around one hundred of them, from little children to teenagers. And on my left I invited all the schoolteachers to come, one hundred of them. I asked them to talk to each other about their sufferings and their expectations. It was so wonderful.

Many people cried during the retreat because they listened to their own suffering and they learned the practical way out of suffering. They got a lot of energy because they had many of the good seeds inside themselves watered. All of them wished the retreat would last longer.

At the regional level, we get the training not only in how to help other people, but how to help ourselves. At the end of a retreat we should come out as a stronger practitioner, a stronger Sangha builder, a stronger and more skillful Dharma teacher. This should be organized regularly.

Please do use your intelligence and your power of organization because Sangha-building is the most noble task. The way out is Sangha. The most precious thing we can offer to our society is Sangha. Everyone has to learn to be a Sangha builder. There are many monks and nuns and laypeople who are excellent Dharma teachers. They can teach Buddhist studies very well in Vietnam and in other countries, but not many have the skill of Sangha-building.

My expectation, my desire is that every OI member will learn the art of Sangha-building, because Sangha-building will bring you a lot of happiness. Sangha is desperately needed in our society, a place where people can come and feel embraced and understood, and learn to see the path of emancipation. A true Sangha is what we need, because a true Sangha always carries within herself the Buddha and the living Dharma. It is the living Dharma that makes the Sangha into a true Sangha, a real refuge for us and for our society.