Dedication of the Beloved Community Garden at Magnolia Grove Monastery

By Peggy Rowe-Ward, Sister Peace in June 2016

“If I have been able to see further, it was only because I stood on the shoulders of giants.” — Isaac Newton

What happens when two giants meet?

Dedication of the Beloved Community Garden at Magnolia Grove Monastery

By Peggy Rowe-Ward, Sister Peace in June 2016

“If I have been able to see further, it was only because I stood on the shoulders of giants.” — Isaac Newton

What happens when two giants meet?

We invite you to take a few moments to reflect on the times when you had an encounter with another person that changed the trajectory of your life. While this is an extraordinary event, it is also an ordinary miracle.

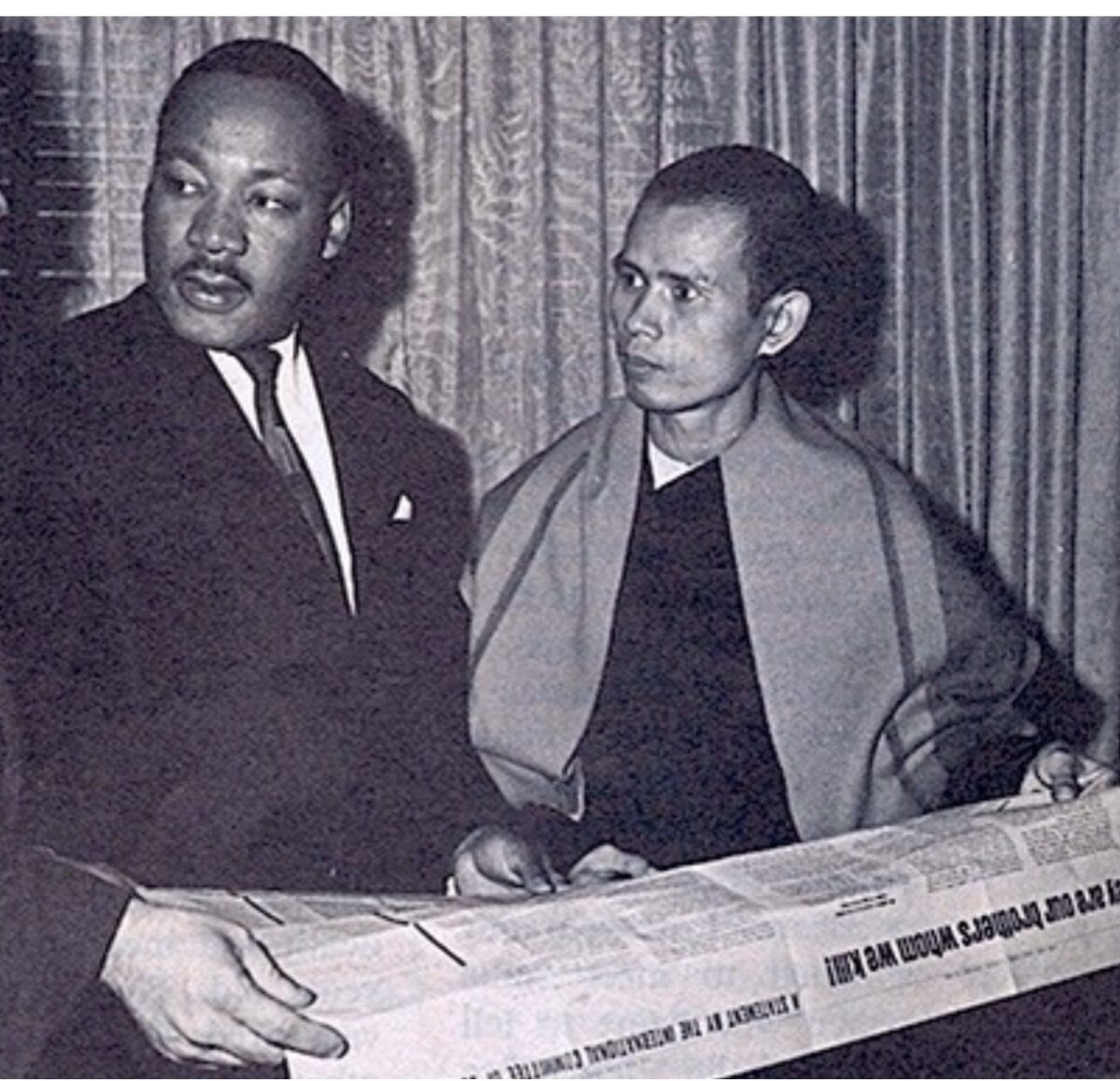

Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. met for the first time in 1966; they met in person one other time before Dr. King was assassinated in 1968. They spent little time in each other’s company, and yet the energy of their meeting continues to ripple out into the world wherever people work for civil rights, peace, and community.

On September 27, 2015, the Beloved Community Garden was dedicated at Magnolia Grove Monastery (also called Magnolia Grove Meditation Practice Center) in Batesville, Mississippi. The garden, with its monumental statue of Dr. King and Thich Nhat Hanh, commemorates the meeting and collaboration of these two bodhisattvas.

A FORTUNATE ENCOUNTER

How did Dr. King and Thich Nhat Hanh meet? And how did they come up with their ideas about peace, nonviolence, and community that were so profoundly at odds with the Western philosophy and religion of their day?

Thay first communicated with Dr. King in June 1965, when he wrote a letter asking Dr. King for his support to end the war in Vietnam. In the letter, Thay explained that the monks who immolated themselves in Vietnam were not committing suicidal acts of despair. Thay wrote, “Sometimes we have to burn ourselves in order to be heard. It is out of compassion that you do that. It is the act of love and not of despair.” 1

A year later, in June 1966, Thay and Dr. King met in Chicago for the first time. Thay describes this meeting: “We had a discussion about peace, freedom, and community. And we agreed that without a community, we cannot go very far.” 2 As a result of this meeting, Dr. King began to speak out against the Vietnam War, even though his closest friends and advisers urged him not to. They feared for his safety and were concerned that opposing the war would dilute their efforts to advance the Civil Rights movement. Dr. King realized that it was part of the Civil Rights movement to speak out against the war and to support the peace movement in the US.

Dr. King nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize on January 25, 1967. Unfortunately, that year no Peace Prize was awarded.

In May 1967, Thay and Dr. King met again in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Pacem in Terris conference organized by the World Council of Churches. Thay was staying on the fourth floor of the hotel, and Dr. King invited Thay to breakfast on the eleventh floor. Thay was detained by the press and arrived late. He was moved that Dr. King kept their breakfast warm and waited for him to arrive before eating. At this meeting, Thay told Dr. King, “Martin, you know something? In Vietnam they call you a bodhisattva, an enlightened being trying to awaken other living beings and help them go in the direction of compassion and understanding.” 3

Later, Thay said he was glad he had a chance to say this to Dr. King, because less than a year afterward, on April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis.

Community members recall that when reflecting on that time, Thay said he was in New York City sick with the flu when Dr. King was shot. Thay was in despair, yet he knew that efforts to end the war in Vietnam were also planting seeds of the Beloved Community. Not long after that, he vowed to himself that even in exile he would redouble his efforts and put all his energy into the practice of building the Beloved Community he and Dr. King had discussed. He felt the seeds they had been planting were not lost; they had begun to sprout and come up everywhere.

Thay loved Dr. King, and any of us who has heard Thay speak about Dr. King has experienced this enduring love. Thay stated that “in loving Martin,” he also experienced love for Jesus Christ. Martin’s deep embodied love for Jesus penetrated our teacher through this energy of love.

REALIZING THAY'S DREAM

During a retreat in Spain in 2014, our teacher suggested to Sister Hy Nghiem, the eldest sister at Magnolia Grove Monastery, that the Magnolia Grove Sangha should somehow commemorate Dr. King and Thay’s shared vision of the Beloved Community. According to Sister Dang Nghiem, the original idea was to commission statues of Dr. King and Thay “to enliven their common aspiration and vision to build a Beloved Community. After we had the sculpture done, we thought of making a garden to appropriately hold the sculpture, and we named it the Beloved Community Garden so that it reflects their vision.” The Sangha commissioned Alexei Kazantsev to craft a sculpture that would be an artistic interpretation of the moment when these two giants met and changed history.

The beloved Fourfold Sangha of Magnolia Grove Monastery then went to work creating the garden to manifest Thay’s dream. Vietnamese lay practitioners are vibrant and generous supporters of the practice community at the monastery, often arriving with produce from their farms, chopping vegetables, and cooking. Many were involved in designing the landscaping for the new statue. Sangha member Margaret from Wisconsin shared, “At one point a large clump of bamboo was dug from another part of the property. A lay friend brought it on his backhoe to the new garden where it looks like it has been forever.”

The statue and garden were dedicated on the last day of the 2015 English-speaking retreat, “Now Is the Time.” This retreat was part of the US tour led by the international Plum Village monastic community. The day of the dedication was a warm one. Sister Chan Khong led a peaceful walking meditation with monastics, retreatants, and friends from the neighborhood, following a spiral path to the Beloved Community Garden. Even though Thay was not there physically, his presence was palpable in the togetherness of over seventy monastics and three hundred lay friends.

Sister Peace opened the dedication ceremony by saying, “In 1966 and 1967, when these two great bodhisattvas met on the heels of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, I was a little girl growing up in Washington, D.C. Little did I know that they would become my teachers and that I would be standing here with you today with the distinct honor to be a part of the dedication of the Beloved Community Garden at the Magnolia Grove Monastery in Batesville, Mississippi.”

Alexei Kazantsev, the sculptor, spoke next. He shared how happy he was to have had a chance to work with the monastics on this sculpture. Having been so familiar with Thay, the monastics would meticulously point out to him, “This is not Thay’s nose,” “Thay’s eyes are much deeper and more penetrating,” and “Thay’s belly is flat and not big like that!” Mr. Kazantsev felt that making Thay’s sculpture was the most challenging and also the most meaningful project in his career. He referred to Thay as “our teacher” and grew to love Thay in the process. Later in the day, Kazantsev gifted the prototype bust of Thay to Sister Chan Khong for the community.

The next speaker, Al Lingo, knew both Dr. King and Thay personally. He said that he had had one day to think about his talk. Not wanting to call attention to himself in any way, he agonized about the task. He met beforehand with Sister Peace to discuss his dedication talk and shared some stories with her. Sister Peace invited him to “share that” and he did, delighting the Sangha with stories that captured the humanity and humor of the two great men. “I have known both of them personally as powerful human beings and teachers,” he said. “Each had a model for what it was that they wanted to manifest. For Thay, this is the Buddha. For Martin, it was Jesus Christ.”

COMPASSIONATE HEARTS UNITED

When Al Lingo finished speaking, Sister Peace invited a surprise guest to come forward. She shared with the gathering that she had invited a friend from Memphis, Kevione Austin, a fifteen-year-old African-American young man, to come up and sing a song. She said, “You know, I had to cajole my young friend to miss his Sunday service and tell his pastor that it would be a great gift to lift his voice in tribute for our dedication today.” The Sangha was silent and rapt when Kevione sang “Beautiful” by the artist Mali Music, a song about the beauty within us all. The loving welcome of the community softened his initial discomfort into a vital life force that moved through his singing. His powerful young voice invoked struggles past and present and the continuing significance of the dream of the Beloved Community.

Sangha member Toby from Oklahoma shared his impressions of this day: “During the ceremony I reflected on violence as one of the causes and conditions that could unite these men as friends and colleagues in peace. Contemporaries born more than eight thousand miles apart, these compassionate hearts united over the ideas of peace brought about by a Beloved Community, now fulfilled in the presence of a Buddhist meditation practice center in Batesville. At Magnolia Grove, we celebrated their collaboration only sixty-one miles south of the site of Dr. King’s assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, fifteen months after he nominated Thay for the Nobel Peace Prize. In his letter to the Nobel Institute, Dr. King stated that Thay’s ‘ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.’”

After the dedication, Sister Peace spoke to musical guest Kevione. She suggested that he invite his entire church to visit Magnolia Grove. A wide grin spread across his face and he said, “I’m going to talk to my preacher about that!” Beloved Community, indeed!

And so we dedicated a tangible monument in honor of peace activists Dr. Martin Luther King and Thich Nhat Hanh in Mississippi, site of so many acts of violence during the Civil Rights movement. At the end of the dedication ceremony, Sister Chan Khong held Al Lingo’s hand on one side and Alexei Kazantsev’s on the other as they led the stream of monastics and friends back to where the walk began.

What happens when two giants meet? Surely the heavens open and the earth trembles as we recognize that we are but one stream of goodness. May we all join together to nourish our worldwide Beloved Community so that peace is truly present in ourselves, all people and beings, and our precious Mother Earth.