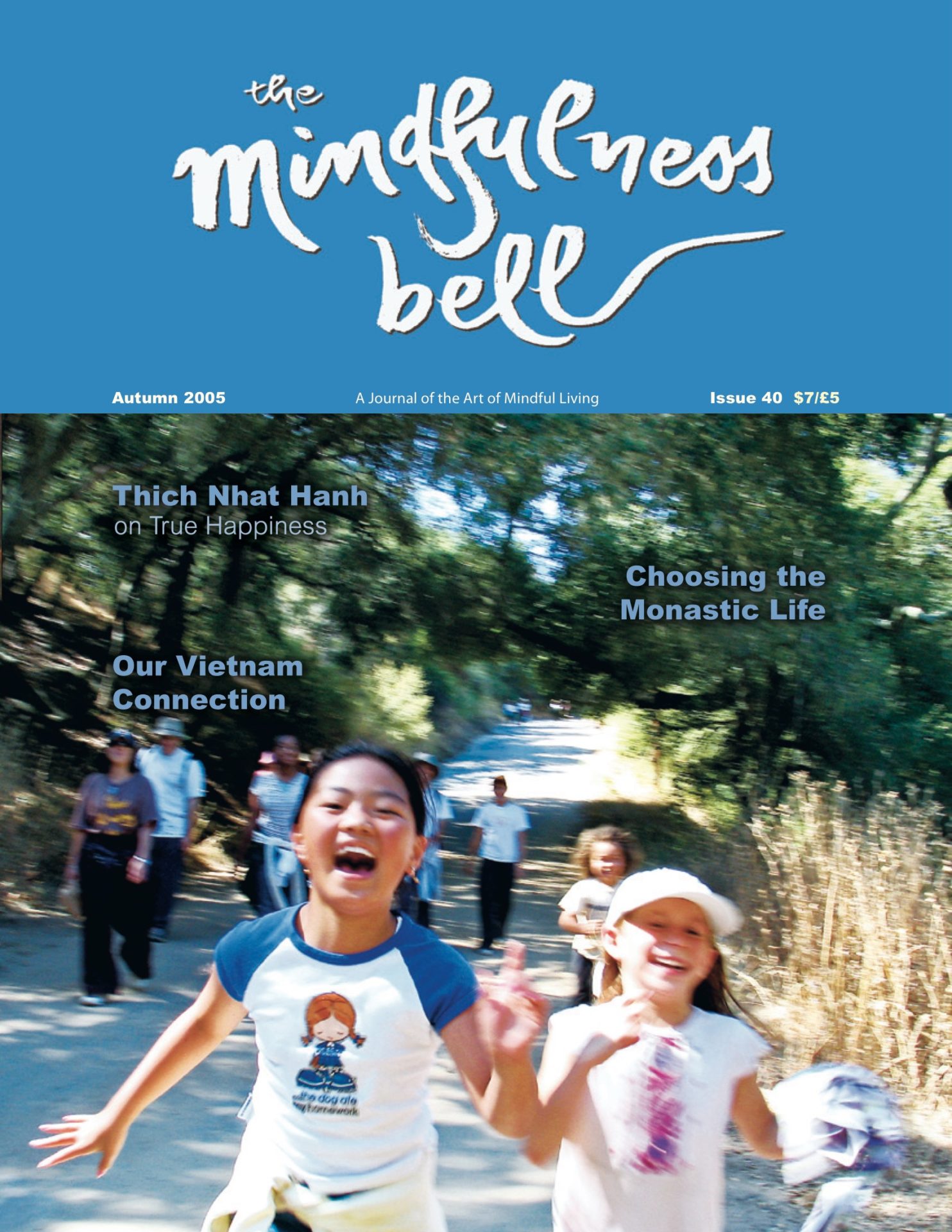

Meow Said the Mouse

By Beatrice Barbey; Illustrations by Philippe Ames

Plum Blossom Books, 2005

Reviewed by Jane Anderson

My seven-year-old daughter Anastasia’s well-used costume box overflows; becoming a cat is her favorite make-believe. She cuddles up close to have her silky fur petted, quietly purrs, and then unpredictably springs away and gleefully bounds around the room, sometimes stopping to hiss at our dog or let out a whining meow.

Meow Said the Mouse

By Beatrice Barbey; Illustrations by Philippe Ames

Plum Blossom Books, 2005

Reviewed by Jane Anderson

My seven-year-old daughter Anastasia’s well-used costume box overflows; becoming a cat is her favorite make-believe. She cuddles up close to have her silky fur petted, quietly purrs, and then unpredictably springs away and gleefully bounds around the room, sometimes stopping to hiss at our dog or let out a whining meow. Meow Said the Mouse by storyteller Beatrice Barbey is a book that fits right in with our house.

The story begins with the baby mouse settling into her own warm bed during a cold night. In her dream the mouse journeys out by herself, takes a chance, and magically transforms into a sleek agile cat with a grand swishing tail. As the cat, she enjoys the warm light that fills her body, and follows her instinct to fill her empty belly. When she turns back into a mouse, she enjoys the swish of her own tail and reminiscent meow. She tells her mother she had a wonderful dream, then without sharing the dream the story loops back to the beginning sentiment of happy little mousehood. A creative way to express our interbeing nature.

Ames illustrates his mother’s story with colorful paper cutouts to evoke a dream world of transformation. The pictures float across the page like Asian shadow puppets, a tradition from which Ames draws. After the tale is told, the book gives a brief history of Asian shadow puppets and directs readers to a Website, where they can download illustrations to make their own cat and mouse shadow puppets. Readers can then become the storytellers of this tale and tales to come. I could not find the shadow puppets on the site listed at the end of the book.

With my daughter, this book opened our story time to talk of the shared spirit, dreaming, and the webbing of life. What better way to prepare for a pounce?

Jane Anderson, Wondrous Breath of the Heart, is a yoga teacher living in Jacksonville, Oregon and practicing with the Pear Blossom Sangha.

Keeping the Peace: Mindfulness and Public Service

By Thich Nhat Hanh

Parallax Press, 2005

Reviewed by Bill Menza

I wish I had this book during the times I worked as a social worker, public health advisor, and consumer safety official. It could have made a great difference, because it spells out clearly and simply how to be an effective peace officer at work, at home, and in our communities. “We all must work to create and sustain peace,” says Thay. We are all practicing law enforcement, because that is what the Dharma is. Dharma, which means “law” in Sanskrit, is about practicing deep insight and a code of behavior “that will bring about mutual understanding, compassion, peace, and happiness” in ourselves and others. Peace means the absence of conflict, violence, and anger.

In the foreword, police officer Cheri Maples tells how her mindfulness practice has helped her to find “the compassion that comes with being willing to be vulnerable and touched by the world.” I remember when she asked Thay at a retreat at Plum Village: “What about us police officers? We see a lot of suffering, which we often bring home. Can you help us?” Thay told her to organize a retreat and he would come, which he did in 2003 at Green Lake, Wisconsin. It was called “Protecting and Serving without Stress and Fear,” and is the foundation for this book.

At the end of each chapter is a helpful “Workplace Practice.” These include such practices as walking meditation, mindful breathing, mindful consumption, selective watering, second body, beginning anew, right speech, deep listening, and a code of ethics.

“Every ordinary act can be transformed into an act of mindfulness. When you breathe mindfully, this is mindfulness of breathing. When you walk mindfully, this is mindfulness of walking. When you look at things mindfully...it’s called mindfulness of looking.” The habit of mindfulness will show us what is going on inside ourselves and around us. This is especially important for those who deal with violent people. Those “who deal with violence should arm themselves with compassion, intelligence, and lucidity. These are the best means to protect yourself.”

Thay asks those in the helping professions to see who they are working with “as the objects of your help and service,” including criminals. In dealing with terrorists Thay says that “the basis of terrorism and violence is wrong perception.” He asks: “Are we capable of talking to the people with whom we are at war and removing their wrong perceptions? We know we cannot remove wrong perceptions by using guns or bombs. Violence leads to more violence and creates more hatred, more enemies, more terrorists.... If you look deeply into the situation, this is clear.”

Dharma Teacher Bill Menza, True Shore of Understanding, lives in Fairfax, Virginia and practices with the Mindfulness Practice Centre of Fairfax and the Washington Mindfulness Community.

Hooked! Buddhist Writings on Greed, Desire, and the Urge to Consume

Stephanie Kaza, editor

Shambhala Publications, 2005

Reviewed by Janice Rubin

One need not look far to conclude that more, bigger, and better have become the institutionalized measures of self-worth today. The three-bedroom house that was adequate to raise two or even four children a generation ago is no longer large enough for many young families today. Some of the homes springing up to meet their perceived needs—“McMansions” or “starter castles” they call them in my neck of the woods—look large enough to decently house an entire monastic order.

Stephanie Kaza, who teaches religion and ecology, ecofeminism, and unlearning consumerism as Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Vermont, has assembled seventeen essays on greed, desire, and the urge to consume written by Buddhist teachers and scholars in Hooked!, a 271-page paperback volume with an eye-catching red cover sporting a huge fishhook.

The essays are organized under three headings: Getting hooked: desire and attachment; Practicing with desire: using Buddhist tools; and Buddhist ethics of consumption. The writers, who run the alphabetic gamut from Ajahn Amaro to Diana Winston, draw links between consumption, environmental degradation, and alienation.

A growing world population and an aspiring consumer class bode ill for ecosystems and human health, they say, spelling out the paths Buddhism offers for unlearning consumerism.

Joseph Goldstein calls “wanting to want” a disease our culture keeps nourishing. We may attain freedom from the addiction to excessive consuming, he adds, through meditative retreats that bring awareness of the nature of desire and through the practice of generosity.

Suffering can be the driving force in consumerism as well as its end result. According to Pema Chodron, ”we turn for relief to what we enjoy—food, alcohol, drugs, sex, work, shopping—because of the underlying insecurity of living in a world that is always changing. We get hooked when we empower [any of these anodynes] with the idea that it will bring us comfort.”

“You are what you download,” Diana Winston opines. “If we feed our minds with greed-inducing information, we are certain to get more greedy….If I practice greed, I will be more greedy. If I practice generosity, I will become more generous. Buddhism 101.”

Although we might agree that it takes a little more than three robes and a begging bowl to live comfortably in our society, and also that we might be content with less than most of us possess, it takes determination and commitment to get unhooked from the addiction to a lifestyle of acquisition. If craving is the root of all suffering, we have a solution to the problem of craving in the Eightfold Path of practice prescribed by the Buddha, according to Pracha Hutanuwatr and Jane Rasbash. They describe initiatives in Southeast Asia to awaken public debate on the differences between Buddhist values and the modern development taking place. In countries like Thailand, where consumerism has become the new religion, they write, alienation has increased due to a sense of inferiority because, “No matter who you are, you are never good enough.”

The essay on green power in contemporary Japan by Duncan Ryuken Williams offers some hope for the planet. If institutional Buddhism, which has traditionally allied itself with the powers-that-be in that country, can develop “greening initiatives through engaged Buddhist alternative energy models” in opposition to the power industry, all things seem possible.

Janice Rubin is a teacher and writer living and practicing in Oakland, New Jersey.

Waking Up to What You Do

A Zen Practice for Meeting Every Situation with Intelligence and Compassion

By Diane Eshin Rizzetto

Shambhala Publications, 2005

Reviewed by Judith Toy

Thich Nhat Hanh compares the Mindfulness Trainings to the North Star. Likewise, Diane Eshin Rizzetto, Dharma heir of Charlotte Joko Beck, presents the Buddhist precepts as: “not rules but lighthouse

beacons, not prohibitions but aspirations. You might also think of a precept as a sign above a door that reads ‘Enter Here’.”

As lay abbess of the Bay Zen Center in Oakland, California, the author presents the precepts as a way of working with her students, much as folks in recovery programs work the Twelve Steps. At first I resisted Rizzetto’s extended metaphor about the dead space encountered by the trapeze artist–– the moment the trapeze stops at the top of its arc before it swings the other way–– a symbol which is threaded throughout the book. Rizzetto suggests we, like the trapeze artist, can be brave enough to let go into that space in our lives. As soon as I was able to drop my resistance and enter that spot at the top of the arc, heart and mind open, her metaphor began to deepen for me.

“The dead spot comes at the end of the swing...when the swinging bar stops moving in one direction and starts moving in the other. Like when you’re highest on a playground swing.” (As a child, I always loved the bump at the top of the swing when I’d fly an inch or two off the seat.) “The whole idea is to use that change of momentum to create the trick.”

The “trick” in this case is to become the benevolent observer of our own lives by entering an uncertain space––waking up to what we do—taking time to watch ourselves without praise or blame, and finally as our practice matures, making the free fall of changing our negative habit energy. By then it’s not a free fall at all; it’s more like a faith fall. And the space is not dead; it’s alive!

Thich Nhat Hanh chose to call the precepts (sila) Mindfulness Trainings. In Rizzetto’s tradition, the precepts are also re-called in the positive. My favorite example in the book: Not Giving or Taking Drugs, Not Indulging in Intoxicants, or Not Clouding the Truth, becomes “I Take Up the Way of Cultivating a Clear Mind.”

Like Good Life, Cheri Huber’s book on the precepts, the format of Rizzetto’s Waking Up to What We Do includes transcripts of discussions with her students, enabling readers to enter at the level of student or teacher or both. In each chapter devoted to one precept she offers an exercise inviting us to engage our observer, go more deeply into our own beliefs, and finally enter the space at the top of the swing of stopping––or not stopping––unfruitful action. This is the nitty-gritty practice, again and again the point of departure in mindfulness practice.

I finished the book with gratitude for this teacher’s approach and for the trapeze metaphor, which is a good reminder as I continue to enjoy the sweet pendulum swing of the Mindfulness Trainings and living the Buddha Way.

Judith Toy, True Door of Peace, is a writer and teacher in Black Mountain, North Carolina.

The Miracle of the Breath: Mastering Fear, Healing Illness, and Experiencing the Divine

By Andy Caponigro

New World Library, 2005

Reviewed by Cheryl Beth Diamond

Andy Caponigro is not only a fine musician, healer, and teacher but a gifted weaver as well. He has created a richly decorated carpet of history, science, philosophy, and spirituality which is very readable. It is interwoven on the firm warp of a practical, warm, and graceful set of breath work instructions.

The book is as much about miracle as about breath since both are intimate manifestations of divine consciousness, original mind, creator spirit, god. For Caponigro, all work with the breath is done in meditation and as such is a form of prayer, song, or resonance with the “breath beyond breath.” What makes this book so appealing is that it is not just another “how to” primer. Though the exercises are clearly written and easy to follow, they are enrobed in the language and atmosphere of contemplation and gratitude, hallmarks of the meditative state.

They address three aspects of the science of breath: freeing blockages to full, unencumbered breath; stabilizing and fortifying the breath; and balancing the in and out breath with attention to the pauses as well. Having been a student of breath science, I am familiar with numerous other techniques that can be calming, stimulating, or balancing. If one were to master the basic exercises presented here and make them part of one’s daily practice, the rewards would be considerable. I was also inspired to return to further exploration of the historical and spiritual roots of breath science and to re-explore other techniques that have specific value, such as the breath balancing potential of alternate nostril breathing.

As a person who comes partly from the world of allopathic medicine and traditional science I take issue with what appears to be an antimedical drift when Caponigro implies that all disease comes from fear and impaired breath. It seems more even-handed to me to say that all disease engenders fear and impacts the breath, and that the body’s capacity to heal itself is therefore adversely affected. If we can increase the fluidity, strength, and balance of our breath, we can positively impact the healing process. Many swamis, saints, and Buddhist teachers have died from intractable cancer in spite of years of meditation, exercise, proper diet, and breath work. However, they most likely did so with a measure of grace and absent the usual pain and fear.

This brings us back to another gift of this book––recognition of the gifts of non-fear and non-pain or non-suffering––which can be cultivated by focused breath work in meditation. It also provides direction for using breathing techniques to cure or mitigate specific disorders.

The final footage of this wonderful carpet is devoted to the spiritual potential of breath work. The breath can be used to open the doors to joy, happiness, peace, gratitude, and love and also to profound states of communion with the divine, holy, godly, and infinite.

Cheryl Beth Diamond, True Opening to Insight, lives and practices in Tucson, Arizona.

Breath Taking

By Susan O’Leary; Illustrations by Emmett Johns

CrossRoads Press, 2005

Reviewed by Barbara Casey

Teacher and writer Susan O’Leary offers us a lovely book of poems and essays. Her words are sparse and simple, with lots of space. Reading through this book reminds me of doing eating meditation: like that one slice of peach, which can satiate my appetite if eaten in full awareness, one short poem of Susan’s can nourish my heart.

The illustrations by Emmett Johns add to the beauty and engender calmness: a bird in flight; the wind blowing curtains through an open window; leaves hanging from a branch.

This book can be carried around on a busy day and taken out for a few moments of respite, used as a reminder to come home to what is really going on, right here, right now.

Here are two of the jewels you will find in Breath Taking:

Sorrow Right under sorrow a reminder of stillness right here now this loss is folded in.

Two Things It is two things two things at once it is here and knowing you are here

simple place finding

when a bird sings dawn it sounds through you Still

Barbara Casey, True Spiritual Communication, is the managing editor of the Mindfulness Bell.

The Dharma of Star Wars

By Matthew Bortolin

Wisdom Publications, 2005

Reviewed by Christine Dawkins

With a voice uniquely his own yet resonant with the simplicity and elegance of Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing, Order of Interbeing member Matthew Bortolin offers the Dharma to a new generation of practitioners in his book, The Dharma of Star Wars. Using concrete and evocative illustrations from the Star Wars epic, Matthew brings the Dharma alive with vivid and fanciful imagery.

“I wanted to make the Dharma available and relevant to young people, the way the Tao of Pooh made Taoist philosophy alive for me,” Matthew told me. He has certainly succeeded—and with the bonus of making Star Wars alive for his readers. I had previously watched only the first episode of the film epic. In anticipation of reading his book, I watched all six episodes, an experience I had resisted based on a preconceived (and false) notion that the movie was essentially violent and dualistic. This time, I applied my Dharma eyes and my experience of the film was rewarding and instructive. What a beautiful reminder that the Dharma is everywhere! Matthew’s book opened a new world for me, one that I could share with my children as well as with the adults in my Sangha.

Matthew’s concrete, easy-to-understand examples make profound Buddhist teachings accessible to the young practitioner. True to our Teacher’s tradition, Matthew provides a practical handbook for his readers, offering the “would-be Jedis” an opportunity to bring the teachings of the Buddha and his Star Wars counterpart, the wise Yoda, into their lives with a series of Zen contemplations. My favorite is an intergalactic version of the sutra on love:

May terrestrial beings, arboreal beings, beings of the skies, beings of the seas and oceans, beings of the stars and asteroids, beings visible and invisible, beings living and yet to live, may they all dwell in a state of bliss, free from injury and sorrow, tranquil and contented. May no one harm another, deceive another, oppress another, or put another in danger.

May all beings love and protect each other just as a Master loves and protects his Padawan.

May boundless love pervade the entire galaxy.

Matthew concludes his book with a timely and beautiful afterword on the nature of violence and the interdependence of good and evil. Acknowledging the violence in the Star Wars movies, Matthew performs a thoughtful analysis of the interdependence of terrorism and social injustice, and the exercise of compassionate action in the face of fear.

“Love is not passive, it is active,” Matthew writes, bringing the essential spirit of Thay’s teachings to the page. “Love is not weak, it is courageous. Love means standing up to those who are harming us and others, and stopping them. We stop them with firm hands, but compassionate hearts. . . . We can respond with fearlessness and nonviolent resolve to bring peace and justice to the world.”

I highly recommend this book and encourage you to return to the Dharmakaya of Star Wars with your Buddha eyes.

Christine Dawkins, True Wonderful Mind, lives and practices in Santa Barbara, California with her friend, Matthew Bortolin, True Silent Festival.