By Marisela Gomez

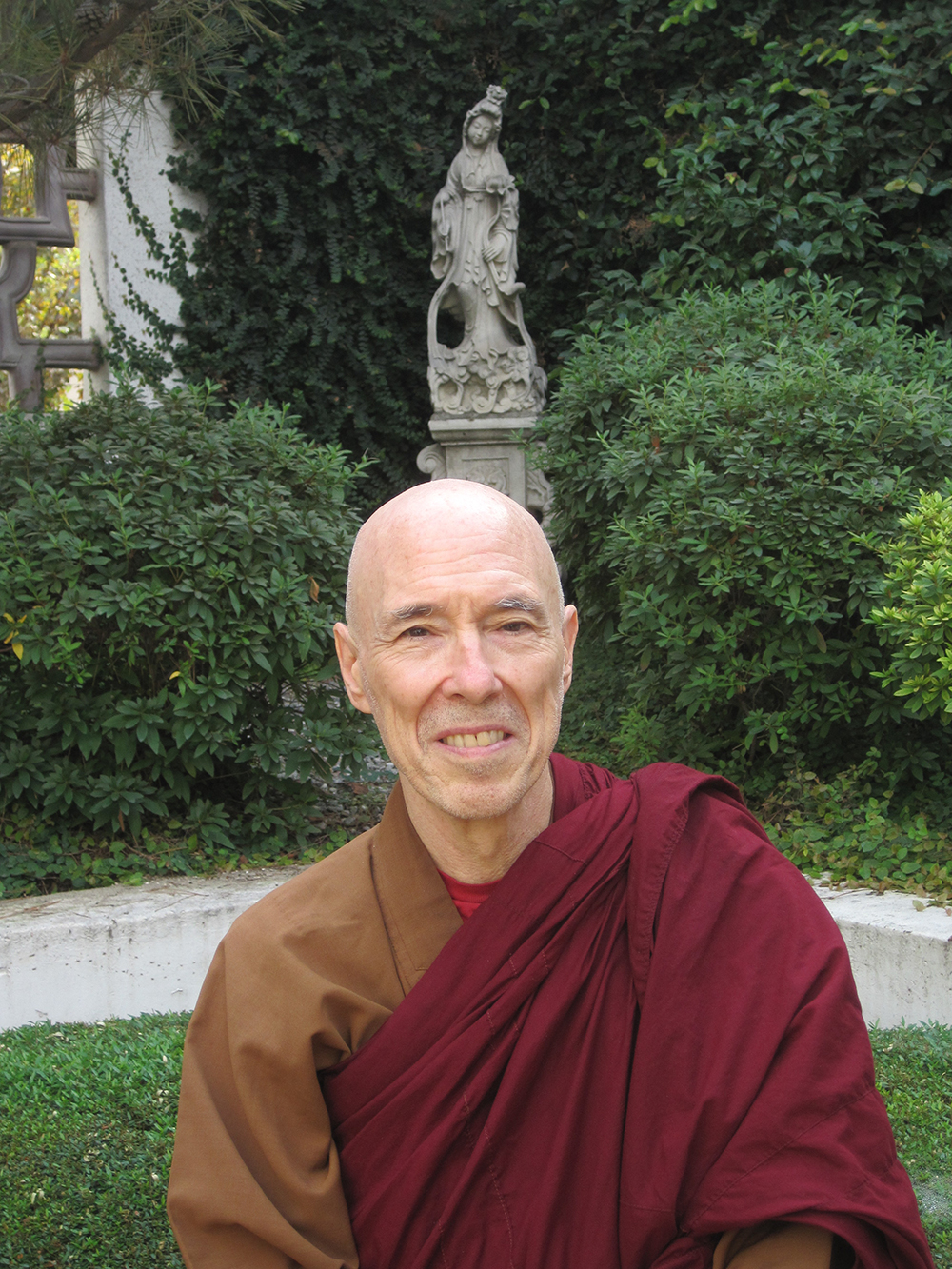

Bhikkhu Bodhi, an American Theravada Buddhist monk, was ordained in Sri Lanka in 1972 and currently teaches in the New York area. He has edited and authored several Buddhist publications and is founder of the organization Buddhist Global Relief, which funds projects to fight hunger and to empower women across the world.

September 5, 2016. It was the last day of the Abhidhamma retreat,

By Marisela Gomez

Bhikkhu Bodhi, an American Theravada Buddhist monk, was ordained in Sri Lanka in 1972 and currently teaches in the New York area. He has edited and authored several Buddhist publications and is founder of the organization Buddhist Global Relief, which funds projects to fight hunger and to empower women across the world.

September 5, 2016. It was the last day of the Abhidhamma retreat, the fourth of a series offered over the last four years by Bhikkhu Bodhi. I was tired, and knew Bhikkhu Bodhi was tired as well after four days of teachings and meditations. He did not say anything about social justice or activism during this or previous Abhidhamma retreats, but having studied his teachings for the past years, I knew that like Thich Nhat Hanh, he had a keen understanding of how the Dharma was necessary in addressing the world’s challenges of injustice. And I felt that like me, others would benefit from his teachings on this. As other retreatants were offering “thank you,” I did as well and asked if he would answer a few questions on activism and the Dharma. – Marisela Gomez

Marisela Gomez: In your opinion, how can mindfulness be a part of activism for social change?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: I see two contrasting ways mindfulness can take on a social function outside its distinctly Buddhist application aimed at the development of concentration and insight. On the one hand, one might practice mindfulness to become more successful in one’s professional life—as a businessperson, an entrepreneur, or a worker—in the belief that mindfulness promotes greater efficiency. Mindfulness can also lead to greater complacency, a bland acquiescence in the status quo. After all, if one is mindful, one can maintain one’s calm and balance through the swings of the economy, the ravages of a nation at war, and the disasters brought on by climate change.

On the other hand, mindfulness can help us to gain greater clarity in fulfilling our responsibility to transform the social order in alignment with our ethical standards. In particular, we should endeavor to express loving kindness and compassion in transformative action, especially in action that will uplift the lives of others and bring relief to those oppressed by socially imposed suffering. This would require that mindfulness operate in a matrix in which there is an ethical motivation to act for the well-being of others and a clear understanding of the deep roots of socially constructed suffering.

MG: Some of the activist work I do is with groups connected to Black Lives Matter and newer groups that have come out because of more clarity around racism in our country. When I’m with them, I try to do small things, like say, “Before we begin the meeting, can we follow our breath for two seconds?” At times there’s pushback: “We don’t have time for that. We have so much to do. How is that going to stop police from shooting another black person?” How do you see us bringing mindfulness into the everyday mundane life of a poor black person struggling for their life?

BB: For poor black persons who are ever subject to police harassment, the practice of mindfulness is unlikely to be a top priority. Their top priority is to survive in a harsh environment, and to gain the respect and support due to them as human beings. Mindfulness and meditation may be more relevant to people from such a background who are training to become community leaders or teachers of mindfulness, who understand the ways of thinking of people from poor black communities. I think the practice of mindfulness, and the clarity and calm it engenders, would resonate well with the ethical thrust of the Black Lives Matter movement. From what I’ve seen, the leaders of this movement already display clarity of thought and firmness of purpose. Thus the practice of mindfulness might enhance these skills and make these people more effective in furthering their aims.

MG: We had a panel discussion two weeks ago with two Dharma teachers in one of the poorest black communities in Baltimore. One of the Dharma teachers was previously a police officer, and the other was previously a judge in Washington, D.C. We invited them to engage around the role of mindfulness in the criminal justice system. One of the people who participated, a young black man, said, “I want you to tell me how I can use mindfulness when a police officer pulls me over. How do I not get angry? How do I not respond in a way that I put my life at risk?” How would you respond to that?

BB: In a situation like this, mindfulness can be extremely beneficial and may even prove to be a lifesaver. If a black person, or anyone else, is harassed by a policeman and responds with anger, this will feed the policeman’s anger, pouring oil on a volatile fire that might flare up out of control. Police officers are, after all, just as human as we are, and if provoked, they might act on impulse and even shoot. But before one responds, if one remembers to be mindful, keeps calm, and directs loving kindness towards the police officer, one can defuse the situation.

If the policeman stops you after you have committed some violation, after pausing for a moment to regain mindfulness, you can calmly remind him that your life is precious, that he shouldn’t think that your violation justifies pulling the trigger. One of the reasons why police killings take place so often, I believe, is because the officer doesn’t see the other person as a human being. Rather, he perceives the other through the lens of preconceived notions and then, in a fit of anger or fear, pulls the trigger. Emphasizing your humanity might elicit a very different response.

MG: There’s been a movement within Buddhist communities to look into what role they can play in social transformation. Groups like White Awake and Buddhist Peace Fellowship are looking into racism inside our Buddhist communities. Many Buddhist communities are majority white. Why are people of color underrepresented? There’s a movement from within the communities to look at racism in our society by looking at what’s going on in our Sanghas. What do you think of that as a way to undo injustices around race and other forms of oppression?

BB: My focus has been less on interpersonal relations and more on what’s taking place in the wider society. As I see it, police brutality is just a symptom of deep distortions and disparities that extend to all the tissues and organs of our social system. Large-scale transformations are needed throughout the social body: in the criminal justice system, which incarcerates black men at far greater rates than whites, often imposing harsh sentences for trivial infringements of the law. Proactively, we should be building adequate social structures to enable all people to live happily and abundantly—whether they be black, brown, or white. We need changes in our social system that can ensure everyone decent housing, basic social services, and meaningful work—not just monotonous jobs that pay substandard wages. The educational system, too, should be vastly overhauled so that people in poor communities, African Americans and others, can receive an excellent education. The social safety net, which has been largely dismantled, needs to be revitalized so that no one falls through the cracks. If we diverted just a small percentage of our military spending to social development, we could ensure that everyone in this country enjoys a decent standard of living.

Our most urgent priority is the climate. I think it likely that, in the years ahead, as climate change starts to unleash its full impact, vast regions of the world will become uninhabitable—sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South Asia, the South Pacific islands—and the people there will have no choice but to migrate, potentially igniting conflict. Here in the US, too, there will be brutal weather disasters, food shortages, and changes in the topography of the country. We have to be prepared for this and act to prevent these problems from spiraling out of control. The climate science is clear, the destructive impacts are already obvious, and the message is indisputable. We have to stop exploring for and extracting more fossil fuels and switch over, promptly and decisively, to an economy powered by clean, renewable sources of energy. Our own future, and the future of the entire planet, depends on making this choice.

MG: You’re one of the few monastic teachers who has given Dharma talks on the Occupy Movement. What drives you to have that kind of energy in Buddhism? So many people think Buddhists don’t know anything about the world, the difficulties. But your Dharma talks are from someone who is in the world with a very clear knowledge of it.

BB: Before I became a monk, I had an interest in current events. When I was in college, I went on peace marches opposing the Vietnam War. But when I became involved with Buddhist practice, I decided that I can’t improve the world until I improve myself. Thus, when I went to Sri Lanka and became a monk, I lived a secluded monastic life, engaged in Dharma study and practice, and hardly paid attention to world events.

My sense of social conscience was revived when I went to live with the elder German monk, Venerable Nyanaponika Mahathera (1901–94), who had left Germany in 1936 and came to Sri Lanka, where he was ordained as a monk. Nyanaponika was my kalyana mitta, my spiritual friend and mentor. I lived with him for almost eleven years, until his death at the age of ninety-three. He had a keen interest in world affairs—not from a worldly point of view, but from a deep sense of compassion, a sense of empathy with humanity. His influence reawakened my sense of social conscience, which had been slumbering through my early years as a monk. Under his influence, my mind opened up and I wanted to understand what’s going on in the world. I came to see that if, as a monk, I was to help people emerge from suffering I had to understand: what are the types of suffering that people are facing today?

American Buddhist teachers typically address what we might call “existential suffering.” They speak to people who lead fairly comfortable lives but are troubled by a sense of inner emptiness. However, when I look out at humanity, I see people in far-off countries battered by brutal wars, people who yearn to live in peace. I see people suffering from hunger and malnutrition, from persistent poverty, from oppressive regimes. I feel that as an expression of Buddhist conscience, part of my task—and our task as Buddhists—is to look into the deep roots of so much suffering, understand their dehumanizing impacts, and try to envision better alternatives. We need to be voices of justice for those who cannot speak up for themselves.

MG: I looked specifically for this merger where teachers are talking about activism in very clear ways … what’s the role of our practice, what do we bring out? So for someone to speak about what’s happening here in the US, it’s wonderful, because it’s a call to us as practitioners, US practitioners, Buddhist practitioners, it is part of our role in this humanity, to bring the two together.

BB: Among the Western monastic teachers here in the US—and there are not many of us—I believe I’m one of the very few who speak out openly on issues with social and political implications. Asian monastics will come forward on social issues that affect their own ethnic communities, but they seldom go beyond that and take a look at the wider society in which we live. I’m sometimes criticized for my outspokenness by “purists” who say, “You’re not following the right way of a monk.” [Laughter] But that’s the way it is. Sometimes one just has to listen to the Buddha that one hears speaking in one’s heart.

Transcribed by Diane F. Wyzga, Radiant Freedom of the Heart

Marisela Gomez is a member of the Baltimore and Beyond Mindfulness Community for activists and people of color. She is involved in equitable and sustainable community rebuilding and enjoys writing and noticing the movement of natural bodies of water.