By Therese Fitzgerald

Two years ago, when we planned the details of a Spring 1991 tour of North America with Thich Nhat Hanh and Sister Phuong, we knew that it would be the longest retreat and lecture tour yet—110 days—and that Thay would need the best support possible. One of his biggest concerns was that he would have to cancel parts of the tour if his strength did not hold out. He could hardly bear the thought of disappointing people.

By Therese Fitzgerald

Two years ago, when we planned the details of a Spring 1991 tour of North America with Thich Nhat Hanh and Sister Phuong, we knew that it would be the longest retreat and lecture tour yet—110 days—and that Thay would need the best support possible. One of his biggest concerns was that he would have to cancel parts of the tour if his strength did not hold out. He could hardly bear the thought of disappointing people. Our thought in the planning of events thus turned to such questions as "How can we conserve Thay's energy?" and "What will he need in order to best offer this public lecture or that retreat?"

In late winter, I received a somewhat cryptic note from a resident at Plum Village wishing me the best of spirits keeping Thay bright company in the midst of the dark state of U.S. involvement in the Gulf War. It came as somewhat of a shock, nonetheless, at the first public lecture in Houston, when Thay described the anger he had felt when President Bush declared war on Iraq, and that he had seriously considered not coming to the U.S. for the spring tour. His decision to come lent a palpable sense of urgency and concentration to all he did with us over the months. The two prominent themes of stopping/calming (samatha) and looking deeply (vipassana) took on a vitality and importance that could not be missed. It was hard for Americans not to feel a crucial sense of responsibility as Thay spelled out the practices of stopping and looking deeply in the face of one of the most massive deployments of high-tech armaments in the destruction of a land and large numbers of its people over the shortest period of war in recent history.

During a question-and-answer session with Thay one evening at the retreat near Houston, a woman expressed her deep despair and sense of isolation among the "gung-ho" residents of her town, just outside a large air force base. So many questions like hers no doubt prompted Thay to emphasize the need for us to establish local sanghas, "communities of resistance," who could support the practices of stopping/calming and looking deeply into ourselves, our families, our society, and the world situation.

The public lecture in Houston revolved around an examination of the Christian roots of nonviolence—a theme that arose out of Thay's contemplation of President Bush's many Christian-based statements defending our going to war. (Set Mindfulness Bell number 4.) I can't help but think that we would have heard much more during the tour on this subject, except that Thay received feedback in Houston, where he was hosted by a Buddhist Unitarian group, that he was "assuming we were much more Christian than we are." Nevertheless, Thay did continue to address the crucial topic of nonduality in skillful ways; but from a more Buddhist perspective, which it turned out was more accessible for the majority of people coming to hear him speak.

The first and last "jogging meditation" instruction Thay gave during the tour was at the Texas retreat. We were invited to continue breathing and counting our steps as we kept apace with Thay, pumping our arms, and jogging to and from Lake Olympia. There was one more spontaneous burst of jogging en masse through the woods at the mindfulness retreat at Mt. Madonna Center in Northern California, when it started hailing during walking meditation.

In Southern California, a nun from Hawaii, Sister Hue Hao, joined us to help cook and care for Thay during the rest of the tour. Not only did this make all the difference in terms of his vigor and ease, but Sister Phuong, Arnie, and I felt buoyed by her kind, attentive presence, as well.

The retreat for environmentalists in Malibu drew from a wide range of backgrounds, as Peter Matthiessen explains in the essay following this one. "To take care of the environment is to take care of the environmentalist," was the heartbeat of this wonderful retreat.

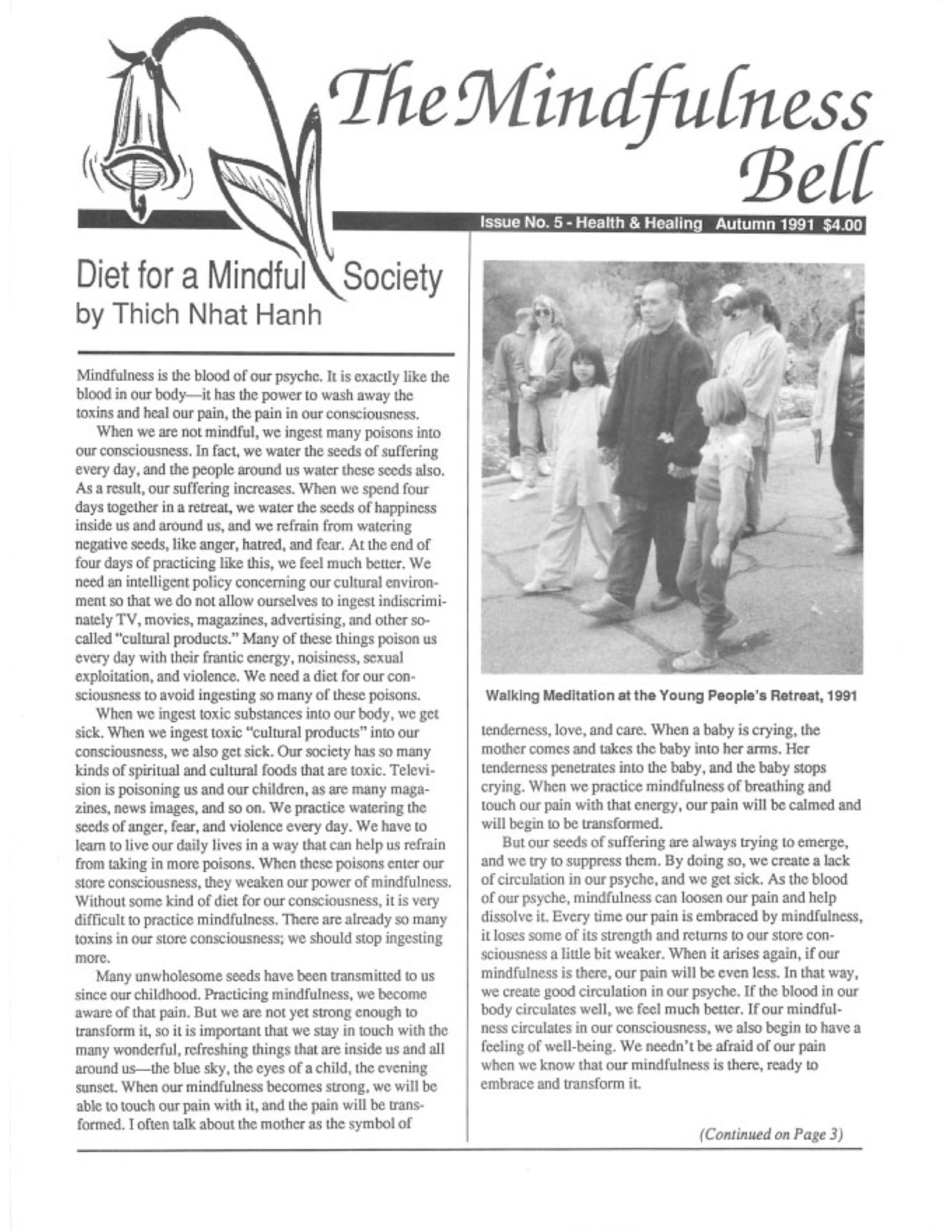

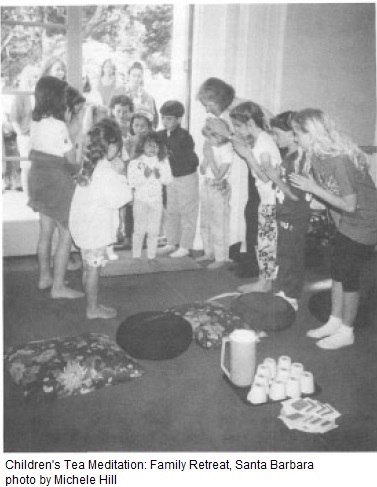

A paradise of blooming flowers greeted us in Santa Barbara with the retreat for young people and families. Walking meditation through the orange grove was so sweet, that I thought I might burst with joy at the sight (and fragrance)! One hundred young people—toddlers to twenty year olds—and 85 adults gathered for this unique retreat. For two years, the team of organizers, "veterans" of the similar 1989 retreat, had been carrying on a very active dialogue and continuing to hostess Family Days of Mindfulness, so the program and practice for the 1991 retreat was rich and strong. Activities for the various age groups were carried out in great mindfulness. After meditation in the morning, the youngest children attended a separate Dharma talk by Mobi Ho. In the afternoon, everything from making meaningful buttons (the kind you pin to your jacket) and brushstroking, to seeing slides about the Vietnamese and preparing parcels for Vietnam, to hearing about civilian casualties in Iraq, to making clay or "junk" sculpted Buddhas was offered. Group discussions were especially fruitful, whether among the nine through twelve year-olds, teenagers, or the parents. The last evening we had a candlelight procession to the pool, where we floated paper-mache boats in commemoration of those who died in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and fleeing Vietnam.

Santa Barbara, fresh with spring flowers, nestled in the mountains by the sea, was the setting for Thay's introduction of the new breathing gatha: In/out, flower/fresh, mountain/solid, water/reflecting, space/free. The young people, with Betsy Rose's help, immediately picked up the images and composed a delightful song, which we spontaneously waltzed to the evening it was presented.

Thay's public lecture in Los Angeles drew almost 1,500 people—a clear sign that Americans need and desire to look more deeply at their situation. He began by introducing the new mindfulness verse. The lecture in Berkeley the following week shone as the most well-attended event of the tour. Nearly 4,000 people sat still for two hours and twenty minutes to hear the words of a wise spiritual friend. The whole evening was a wonderful, affirming celebration of the joys and the work involved in living mindfully. Glorious flower arrangements decked Thay on either side, and a lovely banner of the new verse for conscious breathing calligraphed in foot-tall letters descended gracefully from the ceiling as Thay entered the stage.

A very brief visit to Yosemite refreshed us as we walked among the conifers, stood in the spray of giant waterfalls, and partook in the "sequoia sangha" by sitting under those great trees on a patch of ground, amid the snow.

It was evident within hours of the beginning of the mindfulness retreat at Mt. Madonna that an extraordinarily ripe group of practitioners had gathered. These were days of deep quiet. In the retreat for helping professionals, Thay challenged the group of medical people, educators, therapists, social workers, and others to keep themselves fresh and at ease in the midst of the great demands from people in need. "We must be aware of our limits," Thay said, encouraging them to bring mindfulness practices into their workplace. The last evening's session of songs, anecdotes, jokes, and even magic tricks reflected a great sense of camaraderie that will, no doubt, nourish the helpers and their clients. More than half of the 225 retreatants received the Five Precepts the last morning. Wendy Johnson was ordained into the Order of Interbeing with the supportive presence of many of the Dharma sisters and brothers from Green Gulch Zen Center, where she lives.

The Day of Mindfulness, attended by 1,100 people, at Spirit Rock Meditation Center was one of the highlights of the trip, as Nina Wise explains in this issue.

Chicago—"warm welcome, cool farewell," Thay said, referring to the extreme heat wave when we arrived for the retreat at a Catholic seminary, and left a week later on a cold, foggy, windy day. During the Dharma talks at this retreat, Thay elaborated on ways we Americans can stop doing violence to ourselves and others, and instead contribute our best gifts to society. "Export democracy and appropriate technology," he urged us, "rather than violent television, films, and junk food. The money used to go to war could support 250,000 people from Tibet, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Iraq to come to the United States to learn your democratic way of life. It would be a completely different story if you had done this for many young Iraqis years ago." Five people—Jack and Laurie Lawlor from Chicago, Catherine and Larry Mandt from Madison, and Lyn Coffin from Ann Arbor were ordained into the Order of Interbeing, strengthening the Midwestern sangha.

Thay's lecture in Philadelphia had many intimate touches, such as the beautiful cloths on the tables at the door, and the cheerful, happy hosts and hostesses greeting people. Thay's talk reflected the fact that many peaceworkers were in the audience, as he emphasized the social responsibility of being peace to make peace. The Philadelphia visit reminds me of all the people who so kindly assisted and supported us along the way—sometimes to the point of a family giving us their homes while they stayed in a nearby hotel, or late-night welcomes and home-cooked meals on terribly short notice. These acts were crucial to our maintaining health and presence of mind on a very demanding tour.

Two hundred forty people attended the mindfulness retreat outside Washington, D.C. During the Dharma talks, and also at the Washington public lecture, Thay addressed the social and political nature of mindfulness practice. The heat was intense during the usual morning time for walking meditation in Virginia, so we did walking meditation to the lake by the light of the full moon, and then listened to a concert by the bullfrogs. The sweet fragrance of honeysuckle filled the air, as fireflies flickered in the forest. The 20 children especially enjoyed this peaceful evening.

Thay's public talk in New York City was held in a place that was only big enough to admit half the number of people who wanted to attend. And the air-conditioning was not turned on (as happened in Washington and Toronto as well), so that the 850 attendees had to be congratulated for their stamina in the sweltering heat. A wild thunderstorm greeted us as we emerged from the sauna/lecture hall. Still, another beautiful Dharma talk. The next morning, we caught a taxi to Chinatown to buy a small teapot and to enjoy a breakfast of noodles and "being in China." Looking at the sign for Dim Sum, Thay reflected on the meaning of the word, "pointing the heart," and he told the Zen story of the woman on the mountain who wouldn't serve the monks tea until they could answer her penetrating questions.

Omega Institute, north of New York City, hosted two retreats. When 90 of us gathered in the main hall the first evening, you could feel the heaviness in the air. Thay sat cross-legged on the stage and in a gentle, yet strong voice, began, "My dear friends..." Anne Cushman's account captures the flavor of this moving and most important retreat (p. 20). The mindfulness retreat which followed had 400 participants, who benefited from the depth of the veteran's retreat, as Thay talked about recognizing suffering and taking mindful care of it Many long-time practitioners of Buddhist and non-Buddhist meditation gathered for this retreat, as did many therapists, medical professionals, social workers, and business people. Three people from Boston—Larry Rosenberg, Andrew Weiss, and Greg Hessel—and two from New York City—Amy Krantz and Phyllis Joyner—were ordained into the Order of Interbeing. At each of the retreats during the tour, one evening was given over to a presentation and discussion of the precepts, especially the Five Precepts. The presentation at the Omega retreat was particularly vibrant, but each of these sessions was lively and provocative. It is obvious that they are becoming alive in people's minds and lives. Altogether, nearly 1,000 people received the Five Precepts during the tour.

The Day of Mindfulness in Boston was "rained in"; that is, rather than being out on the lawn, 800 of us fitted snugly into a lovely, old gymnasium. Somehow, we even managed lying-down meditation together.

The retreats in Canada were for the Vietnamese. The one public lecture in English was in Toronto, attended by 400 people. The air was stifling with double the capacity squeezed into the room, but Thay delivered a beautiful talk gathering up all the basic teachings of the tour.

These nine retreats, two days of mindfulness, and public lectures were actually just half of the tour. Arnie and I didn't attend many of the retreats conducted in Vietnamese, which were in Texas, Malibu, Santa Cruz, Virginia, Toronto—where thirteen Vietnamese-Canadians were ordained into the Tiep Hien order—and Maple Village, outside of Montreal; nor did we attend many of the lectures in Vietnamese—held in Houston, Santa Ana, San Diego, San Jose, Philadelphia, Washington, Toronto, and Montreal. But it was obvious, even without understanding the language, that these retreats and lectures were of critical importance to a people in diaspora needing to renew the value of these Buddhist teachings that have been in their culture for nearly 2,000 years, and find new meaning in them in this difficult situation, where Confucian parents (i.e. belief in a tightly-knit family under the parents' authority) and Westernized, "individualized" children have such a vast generation gap. Thay's recommendation for flexibility on the part of both parents and children included hugging meditation and listening more deeply. We hope to share more of the kinds of issues Thay addresses with the Vietnamese community in future issues of the Mindfulness Bell.

Now I am at Plum Village, in southwestern France, for the month-long Summer Retreat, where people from all over Western Europe, North America, and such places as India, Saudia Arabia, and Yugoslavia, are benefiting from the teachings and practices Thay shared while visiting the U.S. and Canada. Someone here asked me how it felt to have so many people gather around Thay. When I think about one and a half million soldiers gathering in Iraq with the support of millions more, I can only see how important it is that as many people as possible be in contact with these practices of calming the mind and looking deeply at ourselves, our family and work life, our society, and our global situation.

Therese Fitzgerald is the Director of the Community of Mindful Living, in Berkeley, California.