By Sister Tam Muoi

Practicing the Eighth of the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings, True Community and Communication, is like peeling an onion. We peel away layer after layer, and there’s always another layer to discover!

If I have a difficulty with someone, it feels uncomfortable. It’s like having a stone in my shoe: I want to resolve the situation.

By Sister Tam Muoi

Practicing the Eighth of the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings, True Community and Communication, is like peeling an onion. We peel away layer after layer, and there’s always another layer to discover!

If I have a difficulty with someone, it feels uncomfortable. It’s like having a stone in my shoe: I want to resolve the situation. On the other hand, when good relations already exist, it’s important to nourish them. Living in Plum Village, we have the practice of watering flowers and appreciating the beautiful qualities in each other, and many of the sisters and brothers are good at that. When I hear a sister watering someone’s flowers, it always encourages me to do that too. I recognise it’s important not to take good relationships for granted and to be proactive.

However, communication is challenging when living in a community. Practicing as a lay person, I could choose where and when I would interact with a particular person. But in a community, I could bump into a person I’m having difficulties with in the bathroom, the kitchen, the dining room or the garden.

I appreciate having fluid, openhearted relationships with everyone in the community. When that fluidity isn’t there, it’s uncomfortable. I know I want to practice with communication difficulties. I’m not good at ‘there’s no problem.’ I want to be proactive, and I have committed to train myself. It’s not just immediately jumping into Beginning Anew; we have other ways we can act. I want to be skilful, and that requires training. I make a lot of mistakes, but I learn by my mistakes.

I have realised that communication was not great in my family. The habitual pattern was to close down if a difficulty was present and to avoid communicating for days, if not weeks. I can see that this habit was violent for myself and the other person. However, the pain from those hurting relationships has encouraged my aspiration to find more skilful ways to deal with difficulties. That is the ‘goodness of suffering’ Thay teaches us about. I want to develop the courage to act differently, to be present for conflict and to be able to go through it without running away.

Recently, Sister Chan Duc (Sister Annabel) has been teaching about how to resolve conflicts, and she said that we can see conflict as a point of growth. That gives me a lot of courage—to see it as an opportunity. In a difficult situation, it will be painful and awkward. That’s normal, but it’s okay. So I take care of that in me, first. It is scary, but I want to be brave. Sometimes it takes longer; sometimes things heal more quickly, but this is the direction to go in.

Writing Love Letters

Thay embodies compassion, and he teaches that love and understanding always go together. You cannot love someone without understanding them. The practice of putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes is important, as well as the practice of taking responsibility for our part in a conflict where blaming is not helpful. Thay always encourages us to go in the direction of non-discrimination and inclusivity, so I’ve tried to take that on board.

Thay has given us concrete practices, like writing a love letter. These love letters have transformed my relationship with my parents. I haven’t just written once, but many, many times. My parents are from a different generation, so they haven’t learnt the skills to express emotion. It’s not good for me to wait for them to express their feelings.

The practice of writing a love letter is to mention everything I appreciate in my parents with my gratitude and then to express regrets about the things I didn’t do well. I send those letters to my parents, with no expectation. Happily, my parents are bowled over by those letters. My mother often apologises and says, ‘I could never write a letter like that.’ And I say, ‘It’s okay, Mum. I’ll do it for both of us!’ They are both touched.

Writing a love letter is something we do in the community as well. If there’s been a difficulty between sisters, to write a love letter can go a long way to cultivate good ground before we sit down together. I think the love letter is a beautiful practice for making a mental shift and being able to say to ourselves, ‘Okay, there is a problem. Instead of looking or concentrating on all the negative things, I will put the negative things to one side—I won’t pretend they’re not there—but I will concentrate, focus and get curious about what is good, healthy and beautiful in our relationship.’

This was a revelation for me. Growing up in a post-Freud England, I am vigilant about repressing things. Putting something difficult to one side could seem like repressing it, but it’s not. It’s promising myself, ‘Yes, I will take care of that, but not yet. When I put it on the back burner or on the shelf, I’ll come back to it. For now, I will concentrate on the positive things, which is a helpful practice, but I know I have to come back to the difficult things. I can’t just leave those things on the shelf getting dusty and hope they’ll go away.’

Many of Thay’s stories have encouraged me to go in the direction of healing relationships: the way to go is in. When I’ve been hurt and something is said that is difficult for me to receive—this happens often in a community; we get our buttons pressed, usually quite often—as Thay teaches us, first I come back to myself to see what feelings have been touched and where I feel them in my body.

Then I investigate my need at that moment. What was my beautiful aspiration? Was it for more space, some rest or even to be spoken to with respect? Where things begin to shift is when I reflect, ‘When the sister said the thing that was hurtful, what might her feelings have been in that moment? What might she have needed? What was her beautiful aspiration in that moment?’

For me, that’s practicing what Thay asks us to do: developing understanding for the other person and seeing where they’re coming from. When I can develop empathy for the other person, it’s always healing, and my heart opens. It gives language to practicing love and understanding together.

White Awareness

When I was an adolescent at home, around the dining room table, arguments occurred where my father argued from his point of view and I argued for my point of view. There was no communication. He didn’t budge; I didn’t budge. Thanks to this practice, I’ve been able to see that our worldviews were very different.

My father—he’s 93 now, so he was born in 1925—went to school before and during the Second World War at a time of British imperialism. He received an education where everything that’s British is best, and we are the strongest, the best and the kindest—there is no doubt that everything we do is correct. He had an incredible confidence, which one might call arrogance. That was so frustrating, but I couldn’t call my father arrogant. He was simply taught that way. He’d not been taught to question. He’d been taught to feel as a white, Western male, entitled and superior. His worldview was chauvinistic, a product of British imperialist education. I was growing up in the 1960s as a feminist, and my dad used to call me a Communist!

Now, thanks to the practice, I realise those arguments were pointless. We wasted so much energy; we both wanted to be loved and recognised by the other. I feel we’ve gotten to that place now; I’ve put all my anger aside because I realise he had no choice: this was his education and the environment he grew up in.

I have the opportunity to be part of a white awareness group we have formed with a few monastics and lay friends to look into white privilege. This is confronting work because I realise I am the child of my father who was brought up in a post-British imperialism environment. This work of looking into our history is important because it wasn’t taught in school. My father always told me it was beneficial for the British to go out to the colonies because it was for the good of those people. It makes me cringe to think of this now, but this was what he was taught.

Now I am looking deeply with our white awareness group, watching videos, reading, researching and investigating. It’s painful and shameful what powerful nations, such as England, did and continue to do to keep their power and increase their wealth. I am carrying my past and my father’s views, and my ancestors are in me. I am becoming aware of how I can communicate unskilfully and create separation if I do not transform this shadow part of my heritage. Many of us aspire for our Sangha to become more inclusive and diverse. But how can this happen when our lay Sangha is largely made up of privileged, middle class, white people unaware of our unearned privileges?

Practising mindfulness helps me to become aware of my inherited sense of entitlement, so that I have a chance to notice my habits, to deconstruct and transform them, to keep my heart open and not exclude. Thay has always practised inclusivity towards lay people of all walks of life—people from diverse backgrounds, genders and worldviews. We need to walk in his footsteps and continue his work.

Another aspect of white awareness work is reflecting on the dynamics of living in a majority Vietnamese community. As an English monastic, I have many opportunities to ask myself the question ‘Am I sure?’; As a young novice, I felt I was right. ‘We are in France; this is how we do things here.’ Over time, like the onion, layers peel off and the depth of understanding between the different cultures changes as I get to know my brothers and sisters better. I am often surprised and challenged, but above all, our interactions are a mirror to reflect back to me my own worldview in that moment, including my sense of entitlement and my view’s inherent emptiness. Can I let go?

My Challenges

Living in this community as a monastic, I’m becoming aware of the challenge presented by my habit energy of expressing views with a strong energy. I don’t necessarily use strong words, although sometimes that might happen too. It’s the energy behind what I’m saying. This energy can make it difficult for some of my sisters to want to share their views.

In society, it’s a positive thing to be able to express your views in a strong way. But in an international community, it’s not giving the space for inclusivity. It’s important for me to be aware of the energy that I put into what I’m saying. It’s not only the words but also the energy behind them.

I’m also practising with is my habit to interrupt with when

I get too excited. Or I interrupt someone who’s speaking rather slowly because I’m impatient. I’m becoming more aware of my desire to interrupt in the moment and the intention behind that. I do my best to be more patient and give space to the other person. Another part of this training is learning how to listen. I enjoy listening during the Beginning Anew practice because I’ve made a commitment to listening, and I know I will listen until the other person has finished. Maybe that will take half an hour or longer, but I’m just going to listen.

It’s more difficult in the coming-and-going of everyday life to stop and listen, especially if the sister takes a long time to explain something. Maybe English isn’t her first language, and culturally it may not be acceptable for her to speak more directly.

I’ve noticed I’m more impatient when I’m tired, especially with lay friends who are new and are only here for one week and want to ask me questions—which is normal. I don’t want to be like that. I want to practise being available. Now, whenever a lay friend comes to me, I do my best to stop what I’m doing. I turn to face them; I mentally put down what I am doing, and I am there for them. I want to listen. It’s been a nourishing practice to do this. That’s something I’m practicing with.

It’s not always easy, but I’ve noticed it brings me a lot of joy. When I write my joys and suffering of the day in my diary each evening, if I’ve brushed someone off, for example, this would be something I would feel ashamed of. But if I was able to turn towards the person, put everything down and be available for that person, the chances are we will have had a nourishing interaction. When I write in my diary that evening, reflecting on what brought me joy, almost always that interaction would be one of my joys. This is the learning.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY ANNICA BAUER AND TRANSCRIBED BY GREG SEVER.

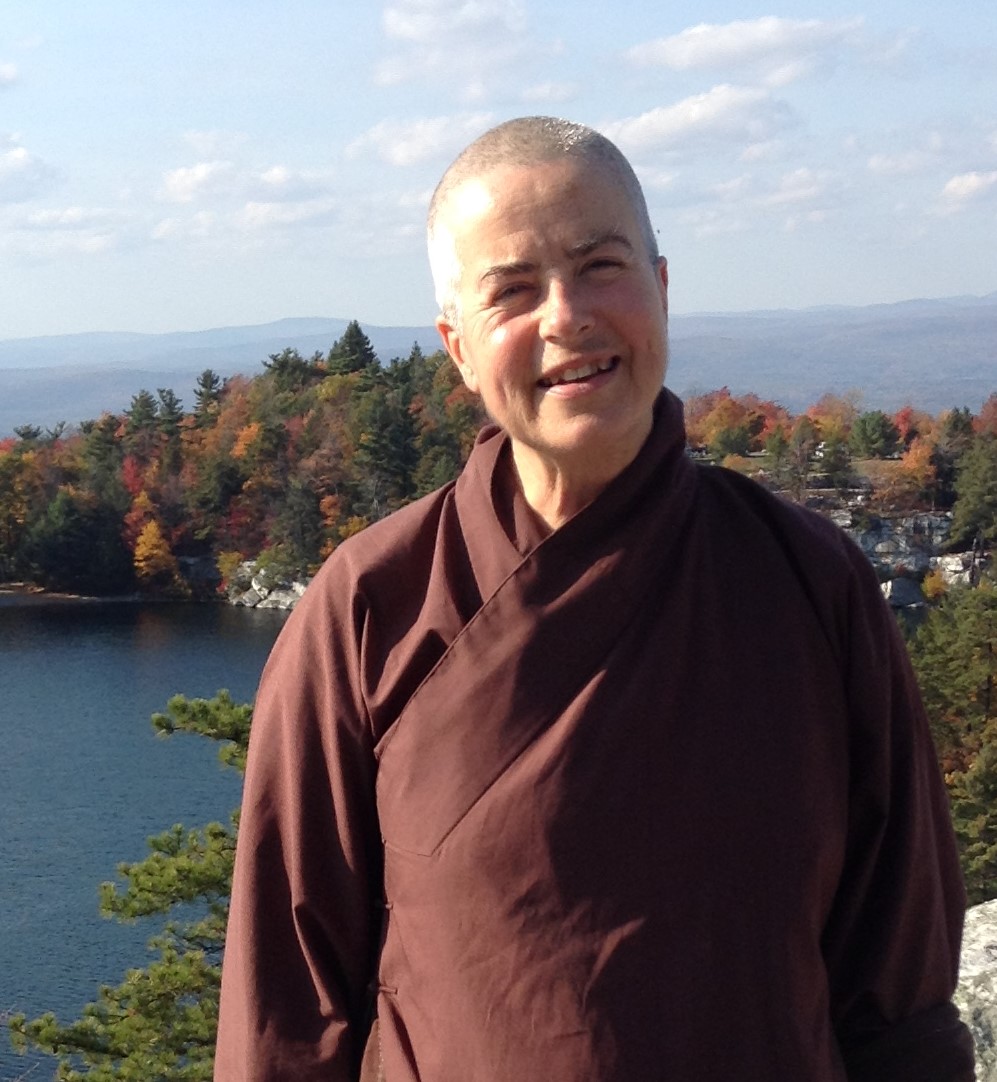

Sister Tam Muoi (translates as ‘Samadhi’) is an English nun currently living in Plum Village. She ordained in 2012 after several careers in France as fashion designer, mother and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)/Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) instructor. From 2014 she spent three years in Blue Cliff Monastery, for which she has immense gratitude, as she was nourished and learnt so much from the American practice community. She enjoys helping to build the new fourfold practice centre, Dharma Mountain, in southeastern France, and takes care of the flower garden in Lower Hamlet, Plum Village.