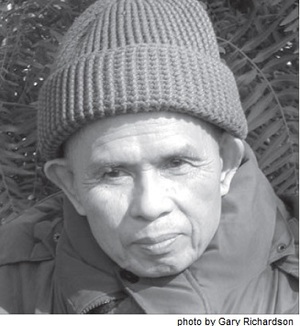

By Thich Nhat Hanh in October 2004

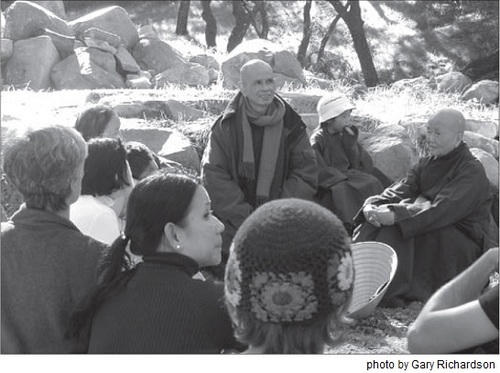

March 28, 2004 – Colors of Compassion Retreat

On March 28th, at the end of the three-month winter retreat, Thich Nhat Hanh and the Sangha offered a three-day retreat called Colors of Compassion, for people of color. Three hundred retreatants gathered to practice mindfulness, listen to teachings, and share with one another the experiences of joy and suffering that come from being a person of color.

By Thich Nhat Hanh in October 2004

March 28, 2004 – Colors of Compassion Retreat

On March 28th, at the end of the three-month winter retreat, Thich Nhat Hanh and the Sangha offered a three-day retreat called Colors of Compassion, for people of color. Three hundred retreatants gathered to practice mindfulness, listen to teachings, and share with one another the experiences of joy and suffering that come from being a person of color.

This section begins with a powerful talk by Thay, given on the last day of the retreat. Following is a story of a courageous couple who escaped Vietnam as boat people, exemplifying Thay’s famous poem, Call Me By My True Names. Also included is an interview with Sister Chau Nghiem, the organizer and registrar of the Colors of Compassion retreat, and a selection of stories and poems of insight offered by retreatants.

There are white people who live in the United States but still do not feel that they have a home here. They want to leave because they don’t feel comfortable with the economic, political, and military policies of this country. In Vietnam it’s the same. There are those who have Vietnamese nationality but who do not feel that Vietnam is their true home They do not feel loved or understood, and they do not feel that they have a future there, so they want to leave their country.

Who amongst us has a true home? Who feels comfortable in their country? After posing this question to the retreatants for contemplation, I responded. I said: “I have a home, and I feel very comfortable in my home.” Some people were surprised at my response, because they know that for the last thirty-eight years I have not been allowed to return to Vietnam to visit, to teach, or to meet my old friends and disciples. But although I have not been able to go back to Vietnam, I am not in pain, I do not suffer, because I have found my true home.

My true home is not in France where Plum Village practice center is located. My true home is not in the United States. My true home cannot be described in terms of geographic location or in terms of culture. It is too simplistic to say I am Vietnamese. In terms of nationality and culture, I can see very clearly a number of national and cultural elements in me –– Indonesian, Malaysian, Mongolian, and others. There is no separate nationality called Vietnamese; the Vietnamese culture is made up of other cultural elements.

There are elements of Chinese, French, and Indian culture in me. You cannot take these out of me. If you remove them, I will not be the person who is sitting here. In me there are also cultural elements from Africa, and beautiful elements of Native American culture in me. In my room I hang a dream catcher so I can contemplate my dreams just for fun.

I have a home that no one can take away, and I feel very comfortable in that home. In my true home there is no discrimination, no hatred, because I have the desire and the capacity to embrace everybody, every race, and I have the aspiration, the dream to love and help all peoples and all species. I do not feel there is anyone who is my enemy. Even if they are pirates, terrorists, communists, or anti-communists, I do not have enemies. That is why in my true home I feel very comfortable.

I heard the story of a young Japanese American man who went into a café. While he was drinking his coffee he heard two young men talking in Vietnamese and crying. The young Japanese American man asked them in English: “Why are you crying?” The Vietnamese men said: “We cannot go back to our country, our homeland. The government there will not allow us to go back.” The Japanese American man got upset and said: “This is not worth crying over. Even though you are in exile and cannot go back to your country, you still have a country, a place where you belong. But I do not have a country to go back to.

“I was born and raised in the United States, and culturally I am American. But I feel uncomfortable because Americans do not truly accept me; they see me as foreigner. So I went to Japan and tried to make it my home. But when I arrived the Japanese people told me that the way I speak and behave are not Japanese and I was not accepted as a Japanese person. So, even though I have an American passport and even though I can go to Japan, I do not have a home. But you do have a home.”

Like the Japanese American in the story, there are many young Asian Americans who have been born and raised in the United States, who are American in their way of thinking and acting, and they want to be seen as true Americans, immersed in this culture. But other Americans do not accept them as Americans because their skin color is yellow. They feel sad and want to go back to Japan, Korea, or Vietnam to find their home. They think: If it’s not in America, my home has to be somewhere else. But they don’t fit in with the culture of their ancestral country either. Other Asians call them “Bananas” because though their skin is yellow, inside they are white, completely American. This also happens to African Americans who go to Africa but aren’t accepted there.

This is not to say that white people have found their home and feel comfortable in the United States. Just like Vietnamese people in Vietnam, many people do not feel comfortable in their own country and want to go elsewhere. Very few among us have found their true home. Even though we have nationality, we have citizenship, and a passport that allows us to go anywhere in the world, we still do not have a home.

Life Is Our True Home

In the Colors of Compassion retreat we have learned and practiced to be in contact with our true home, the true home that cannot be described by geographical area, culture, or race.

Every time we listen to the sound of the bell in Deer Park or in Plum Village, we silently recite this poem: “I listen, I listen, this wonderful sound brings me back to my true home.” Where is our true home that we come back to? Our true home is life, our true home is the present moment, whatever is happening right here and right now. Our true home is the place without discrimination, the place without hatred. Our true home is the place where we no longer seek, no longer wish, no longer regret. Our true home is not the past; it is not the object of our regrets, our yearning, our longing, or remorse. Our true home is not the future; it is not the object of our worries or fear. Our true home lies right in the present moment. If we can practice according to the teaching of the Buddha and return to the here and now, then the energy of mindfulness will help us to establish our true home in the present moment.

According to the teaching of the Buddha, the Pure Land lies in the present moment; nirvana and liberation lie in the present moment. All of our spiritual and blood ancestors are here if we know how to come back to the present moment. My true home is the Pure Land, my true home is true life, so I do not suffer or seek, I do not run after anything anymore. I very much want all of you who have come here for the retreat, whether your color is black, white, brown, or yellow, to also be able to practice the teaching of the Buddha in order to come back to the present moment, penetrate that moment and discover your true home. I have found my true home. I do not seek, I do not worry, I do not suffer anymore. I have happiness, and I want all of my friends, students, and disciples to be able to reach your true home and stop trying to find it in space, time, culture, territory, nationality, or race.

The Buddha offers us wonderful practices so we can end our worries, our suffering, our seeking, our regrets, and so we can be in contact with the wonders of life right in the present moment. When we have the mind of nondiscrimination, we can open our arms to embrace all people and all species and everybody can become the object of our love. When we can do this, we have a true home that no one can take away from us. Even if they occupy our country or put us in prison, our true home is still ours, and they can never take it away. I speak these words to the young people, to those of you who feel that you have never had a home. I speak these words to the parents who feel that the old country is no longer your home but that the new country is not yet your home. Perhaps you can grasp this practice so you can find your true home and help your children find their true home. This is what I wish for you.

Civilization Is Openness and Tolerance

If you have only one way of thinking, one way of behaving, then you are confined to the limits of your culture. With your habitual way of thinking, you imprison yourself and you cannot understand the suffering, the difficulties, the dreams of people of other races or other nationalities. You have a view about freedom, about happiness, about the future, and you want to force that view upon other cultures, other nations, other groups of people, and you create suffering for them. You think that everybody has to follow a certain economic model, a certain way of thinking, and only then are they civilized. When you think in this way, you have tied yourself up with a rope, and you cause danger and suffering for yourself and others.

We need to learn to let go and be open to other ways of thinking and behaving. We should not think of ourselves as superior in terms of race, science, or ideology. We have to practice to open our hearts, to learn about other cultures and other ways of thinking and behaving, so we can establish communication with people of other nations. If you were born and raised in the United States you should not let the American culture imprison you. Try to learn about the country your parents and ancestors came from. This will help you develop good communication with your parents and your ancestors; otherwise you may be cut off from the cultural stream that is one of your deepest roots.

Do not think that the culture and education you received growing up in the United States is superior; this is narrow-minded. We have to open our hearts to learn about the cultures of Asians, Africans, Europeans, and others. Europeans think and behave differently than Americans, even though many Americans have European ancestors. When we have a stubborn attitude, caught in the values, culture, and way of thinking of our own civilization, we are narrow-minded and isolated. The United States right now is isolated politically and militarily, and in the way Americans think and respond to violence and terrorism. It is not the same as the way Europeans think and respond. We need to listen to the Europeans and to people of other nations. We need to learn to let go of the view that our way of reacting and behaving is the best. When we are able to practice the Buddha’s teaching and come back to the present moment, we are in contact with our true home. Then we are not narrow-minded, we are not discriminating, and our hearts are open to embrace all races, all cultures.

To be civilized means to be open-minded, to offer space to others to live according to their views. Civilization is opening our arms to embrace all races, all people, all species; it is not thinking that our race or our culture is superior to all others. If young people can open their hearts wide to learn about their own and other cultures, they will begin to have rich insights. They can help those who are still isolated and caught in their own culture to come together with those from other cultures. This will allow understanding and acceptance to grow, remove boundaries, and heal conflicts.

Speaking to Young People

If you have a great aspiration to learn about other cultures, to go to other countries and to help people accept and understand each other, you have a very great ideal. With that ideal you will not get stuck in despair, blaming others for your difficulties; instead your life will be very meaningful. I am sharing these words with the young people. Many young people have no path and don’t know what to do with their life each day. So they turn to drugs or alcohol and waste their lives. This is such a pity, because each young person can become a great bodhisattva, a great enlightened being whose deepest desire is to help people and bring together those who are separated by hatred or cultural difference.

Dear Sangha, I don’t want to be narrow-minded. I don’t say that Vietnamese culture is the best. Vietnam has many good things, but also many negative things. Buddhism has many good things, but also many negative things. One shortcoming of Buddhism is that we just talk, talk, talk about Buddhism but we do not practice. We can talk beautifully about nonself but we have a big sense of self, a huge ego.

I have the capacity to see the good and beautiful things in other cultures and spiritual traditions. My true home is vast, immense. And my two arms can embrace all nations and all religions. I do not hate, I do not have any enemies, even the terrorists and those who wage war on terrorism. I only love them. I just want the opportunity to come close to them, listen to them, and help them to let go of their wrong perceptions, hatred, and violence. I do not hate dictators, communists, or anti-communists. I want to come close to them, help them understand, and let go of the views they are caught in.

There is no hatred in my true home; therefore I have happiness. Even though there is discrimination, violence, and craving in life, I use these things as nourishment for my practice. It is just like a garden: wherever there are flowers there has to be garbage. If you leave flowers for five or ten days they will become garbage. An intelligent gardener will collect all the garbage to make compost and so bring forth an abundance of fruits and flowers. It is not a matter of not having garbage, it is a matter of knowing how to transform garbage into flowers.

Surrounding us are many wonders: the blue sky, the white clouds, the blossoming flowers, the singing birds, the majestic mountains, the flowing rivers, countless animals and birds, the sunlight, the fog, the snow; innumerable wonders of life. The Kingdom of God is here in the present moment, but because we have hatred and discrimination we are not able to be in touch with the wonders of life.

The Buddha teaches us not to be foolish, not to run after the objects of desire: riches, fame, power, sensual pleasure. There are people who have a lot of money, power, fame, and sex, but they suffer endlessly; some even commit suicide. When we listen to the Buddha and come back to the present moment to be in touch with the wonders of life, we become rich, we become free—free from objects of craving—and we have the opportunity to recognize our wonderful true home. If we have found our true home then we will have enough love and understanding to help transform and heal the wounds caused by violence, hatred, and discrimination.

No Enemies

When I ask: “Do you have a home yet?” you might say: “Not yet. But with this teaching and this practice I can have my home.” It’s true. The teaching of the Buddha is the teaching of dwelling peacefully and joyfully in the present moment. If we know how to come back to the present moment and generate the energy of mindfulness, concentration, and insight, then we will be in touch with the wonders of life. We will have happiness immediately. We will have insights. We will no longer discriminate, no longer be narrow-minded. And we can open our arms to embrace all species, all peoples, and we have no enemies. To have no enemies is a wonderful thing. When we have no enemy, no reproach, no blaming, then our mind is light like a cloud. I have no discrimination or hatred, so my mind is light and I have great happiness. I want you to be able to practice like that so that you have your true home, so that you do not accuse and judge the people who have caused you suffering. Do not look at them as your enemies, but see them as people who need understanding and compassion, so that you can help them. That is the bodhisattva’s way of looking.

We can all have this way of looking: when we are able to look in this way, we can call ourselves the children of the Buddha. To call ourselves children of the Buddha, we need to have the eyes of the Buddha, the eyes of compassion, the eyes of love. “Looking at life with the eyes of compassion” is a phrase from the Lotus Sutra. We use the eyes of compassion to look at all people and see that they are all our loved ones. We can help Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, anyone. Nobody is our enemy.

What Is Your True Name?

Now I want to ask you a second question: “What is your true name?” Tell me. What name do you feel most comfortable with, most happy with? What are your true names? I have written a poem on this contemplation called “Please Call Me By My True Names.”

This poem was based on a real event. There was an eleven-year-old girl escaping from Vietnam with her family and other people. She was raped by a pirate, right on her boat. Her father tried to intervene, but the pirate threw her father into the sea. After the child was raped she jumped into the ocean to commit suicide. We received the news of this event one day in our Buddhist Association office in Paris. It was so upsetting to me that it kept me from sleeping; I felt anger, blame, despair. But if we are practitioners we cannot let blame and despair drown us; we have to practice walking meditation, sitting meditation, mindful breathing, and deep looking.

That evening in sitting meditation I saw myself being born as a baby boy into a very poor fishing family on the coast of Thailand. My father was a fisherman. He had never gone to the temple, he had never received any Buddhist teaching or any education. The politicians, educators, and social workers in Thailand never helped my father. My mother was also illiterate, and she did not know how to raise children. My father’s family had been poor fishermen for many generations —my great grandfather and my grandfather had been fishermen too. And when I turned thirteen I became a fisherman. I had never gone to school, I had never heard of the Buddhadharma, I had never felt loved or understood, and I lived in chronic poverty, persisting from one generation to the next.

Then one day another young fisherman said to me: “Let’s go out onto the ocean. There are boat people who pass near here and they often carry gold and jewelry, sometimes even money. Just one trip and we can be free from this poverty.” I accepted the invitation. I thought: We only need to take away a little bit of their jewelry, it won’t do any harm, and then we can be free from this poverty. So I became a pirate. The first time I went out I did not even know that I had become a pirate. But once out on the ocean, I saw the other pirates raping young women on the boats. I had never touched a young woman, I had never even thought about holding hands or going out with a young woman. But on the boat there was a very beautiful young woman, and there was no policeman to forbid me, and I saw other people doing it, and I asked myself: Why shouldn’t I try it too? This may be my chance to try the body of a young woman. So I did it.

If you were there on the boat and you had a gun, you could shoot me. But shooting me would not help me. Nobody ever taught me how to love, how to understand, how to see the suffering of others. My father and mother were not taught this either. I didn’t know what was wholesome and what was unwholesome, I didn’t understand cause and effect. I was living in the dark. If you had a gun, you could shoot me, and I would die. But you wouldn’t be able to help me at all.

As I continued sitting, I saw hundreds of babies being born that night along the coast of Thailand under the same circumstances, many of them baby boys. If the politicians and cultural ministers could look deeply, they would see that within twenty years those babies would become pirates. When I was able to see that, I understood. When I put myself in the situation of being born in a family that was uneducated and poor from one generation to the next, I saw that I would not be able to avoid becoming a pirate. When I saw that, my hatred, my resentment, my reproach vanished, and I felt that I could love that pirate.

When I saw those babies being born and growing up with no help, I knew that I had to do something so that they would not become pirates. The energy of a bodhisattva arose in my mind, the energy of love. I did not suffer anymore, but I had a lot of compassion and I could embrace not only the eleven-year-old child who was raped, but also the pirate.

When you address me as “Venerable Nhat Hanh,” I answer “yes,” but when you call the name of the child who was raped, I also answer “yes.” And if you call the name of the pirate, I would also answer “yes.” Because they are also me. If I had been born in that area under those circumstances I would also have become the pirate. I am the young girl who is raped by the pirate, but I am also the pirate that rapes the child. And so I could embrace both of them, in order to help not only that young girl but also the pirate. I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones, my two legs as thin as bamboo sticks. And I am also the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to Uganda. Those poor children in Uganda do not need bombs, they need food to eat. But here in America I live by producing bombs and guns. And if we want others to buy guns and bombs, then we have to create wars. If you call the name of the child in Uganda, I answer “yes.” And if you call the name of those who produce the bombs and guns I also answer “yes.” When I am able to see that I am those people, my hatred is no longer there, and I am determined to live in a way that I can help the victims, and I can also help those who create the wars and destruction.

So, when people call us African Americans, we answer, “yes.” When they call us Africans we answer, “yes.” When they call us Americans, we also answer “yes.” When people call the names of those who are discriminated against, we answer “yes.” And when they call the names of those who are discriminating, we also answer, “yes”—because all of them are us. Within us are the victims of discrimination as well as the perpetrators of discrimination. When we know that we are all victims of ignorance, violence, and hatred, then we can love ourselves and also love others. We have to practice in such a way that we free ourselves from thinking and feeling that injustice has been done to us, that we are inferior, that we are without value. The teaching of the Buddha can help us to attain the wisdom of nondiscrimination that can free us from our inferiority complex. Only when we are free can we help others in the same situation, as well as those who discriminate and exploit. We do not look at them as our enemies anymore, but we see that they need our help because they are also victims of ignorance and of the narrow-minded aspects of their traditions.

In 1966 I gave a Dharma talk at a church in Minneapolis, and afterward I was very tired. I walked slowly in meditation back to my room so I could enjoy the cold, fragrant night air and be nourished and healed. While I was walking, taking each step in freedom, a car came up from behind and, braking loudly, stopped very close to me. The driver opened the door, looked at me and shouted: This is America, this is not China. Then he drove away. Maybe he had thought, This is a Chinese person who dares to walk in freedom in America, and he could not bear it. This is America, only white people can live here. And Chinese people, how dare you come here and how dare you walk with such freedom? You have no right to walk in this way. This is America, this is not China. That is discrimination against nationality, against race. But I was not angry—that was the good thing about it—I thought it was funny. I thought: If he would just pause for a moment, I would tell him, “I agree with you one hundred percent, this is America, this is not China: why do you have to shout at me?”

We know that the seed of discrimination lies in all of us. Once in New York a black woman shouted at me, even though I am also a person of color—only a different color. But because I wore a brown robe and I walked in freedom, she could not bear it. So don’t say it is only white people who discriminate. The oppressed and the oppressors are inside all of us, and our practice is to attain the wisdom of nondiscrimination.

So when somebody calls me Nhat Hanh, I answer “yes”; when you call me Bush, I answer “yes”—because Bush is also my name. If you call me Saddam Hussein I will answer “yes”—because I am all of them. I don’t want Mr. Bush to suffer; I don’t want Saddam Hussein to suffer. I want everyone to be happy and free because they are my beloved ones. Right now, living the life of a bodhisattva, I have no enemies because I have no discrimination.

I want all the practitioners who come to Deer Park to practice so you can have this mind of nondiscrimination, so you can rebuild your life and become free. In this way you can help young people, whatever their color, to reach this freedom. Then they will be able to help build their community, and help everyone around them.