By Sister Chan Khong

In 1975, Thich Nhat Hanh and I moved with several fliends to a house near Fontvannes, France. The war in Vietnam had ended and we were cut off from our country with no way to help. We named our community Les Patates Douces, Sweet Potatoes. In Vietnam, when peasants have no lice, they eat dried sweet potatoes. It is the poorest food, and we knew we needed some way to be in touch with the poorest people in our country.

By Sister Chan Khong

In 1975, Thich Nhat Hanh and I moved with several fliends to a house near Fontvannes, France. The war in Vietnam had ended and we were cut off from our country with no way to help. We named our community Les Patates Douces, Sweet Potatoes. In Vietnam, when peasants have no lice, they eat dried sweet potatoes. It is the poorest food, and we knew we needed some way to be in touch with the poorest people in our country. Thanks to that house and land, we were able to heal some of our wounds and appreciate the beauties of France.

Life at Sweet Potato Community was beautiful, but I felt forlorn. More than anything, I wanted to help the hungry children of Vietnam. Then, one day in my meditation, I realized that I could go to Thailand, Bangladesh, or another country to work for social change. There was so much suffering in the world. If I could not help the Vietnamese at this time, why not help somewhere else? In less than a month, I flew to Bangkok and started working in the slums with two Thai friends. But, within a few weeks, I realized that my friends did not do things as I did. I could not reproach them for not following my advice. I knew I was ignorant of their culture and could not impose my plans on them. After three-and-a-half weeks, I decided to return to France. On the way home, I stopped in India and Bangladesh, and I saw the great misery there. Children and adults were so thin they looked like skeletons under the burning sun, as they canied huge bags of rocks and soil. In the mines, the daily wage was less than the price of one kilo of rice. These workers could barely feed themselves, much less their families. I tried to find good local organizations that I could support.

After six weeks, I returned to France, even sadder than before. I had been unable to help anywhere. All I could do at Sweet Potato was to immerse myself in sitting meditation, walking meditation, planting-lettuce meditation, doing everything while following my breathing to stay focused and not carried away by my sadness or thoughts. After many months, I had an insight. Because I was born in Vietnam, I knew the language, culture, and moral values of Vietnam; I was an expert in that part of the world. I had to devote all my energies to finding ways to help there!

A few weeks later during sitting meditation, I remembered a sentence in a letter from my sister: "The medicine you sent Mother for hypertension was very useful, but she didn't need the other medical supplies you sent, so we sold them in the market, and with that money we were able to buy several hundred kilograms of rice." When I read the letter, I had felt sad, but in my meditation, I realized that this was the solution! If I could not send money to the orphans without its being confiscated by the new regime, I could send medical supplies for them to sell at the market.

Thay always teaches that when we are in a difficult situation, if we calm ourselves, we may find a solution. But he also says that the first solution that comes into our mind may not be the best; in a few days, another solution may arise that is even better. So I continued to practice sitting and walking meditation, sowing fresh, calm seeds of peace in my mind, and after a few days, I remembered another sentence in the letter. My sister had written that she was interrogated at the police station several times because of her relationship with me. I knew that if I wanted to send medicine to hungry children, I could not use my own name. So, I began sending parcels of medicine to social workers we had worked with in the past, and with each package I gave myself a new name and wrote in a different handwriting. If I used my name, the workers could get into trouble. I enclosed a letter saying that I was a person living abroad who had lived in the same province in Vietnam as that social worker. Sometimes I was a nun, sometimes an old lady, sometimes a little girl. I wrote that I wanted to send medicine to the social worker, but that if she did not need all of it, she might wish to exchange some for food and share it with hungry children. Then I asked her to send me the addresses of some destitute families so that I could send aid to them directly. In tltis way, I began to accumulate a list of the poorest families.

In just a few months, I had more contacts than I could stay in touch with by myself. I could only send packages to 200 or 300 families by myself, because I was concerned that my address would become suspicious to the communists. So I decided to ask a number of young Vietnamese refugees who came to Sweet Potato to help me.

This made the work even more enjoyable. I was able to get in touch with our network of sponsors, and I could establish a relationship between the sponsors who contributed the funds, the young refugees who helped me write the letters and pack the medicine, and the children who received the medical supplies. I tried to be deeply in touch with each child, to find out his or her worries and aspirations. With this new project, I was able to correspond with each child. In my letters, I taught them how to enjoy the many positive things around them, not just the food and medicine, but their healthy eyes that opened to a world of shapes and colors and many other beauties of their homeland. In some cases, I was also able to help the parents through the child. It is difficult to teach adults when you are giving them money; they might feel offended. So, I tried to teach the children in ways that could also benefit the parents. In just two years, we set up dozens of small groups of young Vietnamese in Europe and Amellca working silently for hungry children.

In October 1982 we left Sweet Potato and moved to Plum Village. Here, many friends and I continue the work to relieve the suffering of poor children and families in Vietnam by sending parcels and finding sponsors to help support our efforts.

One day, seeing how absorbed I was wrapping parcels for hungry children in Vietnam, Thay Nhat Hanh asked me, "If you were to die tonight, are you prepared?" He said that we must live our lives so that even if we die suddenly, we will have nothing to regret. "Chan Khong, you have to learn how to live as freely as the clouds or the rain. If you die tonight, you should not feel any fear or regret. You will become something else, as wonderful as you are now. But if you regret losing your present form, you are not liberated. To be liberated means to realize that nothing can hinder you, even while crossing the ocean of birth and death."

His words pierced through me, and I remained silent for several days. No, I was not prepared to die. My work was my life. Being a nun in the West, I do not carry undernourished babies in my arms, but teenagers and adults do cry silently as they share the stories of their childhoods of sadness and abuse. By listening attentively to their pain and helping them renew themselves, I am able to help heal many of these wounded "children." I also had found ways to help the hungry children, despite the difficulties. I knew that every time people received one of my packages or some other helping act, new hope was born in them, and also in their sponsors in Europe and America. If I were to die suddenly, who would continue this work?

When Thay asked me about dying, I contemplated many practical questions while following my breath. I was not exactly trying to find a solution. I knew the ability to find one was in me and that when I was calm enough, an answer would reveal itself. So I continued to breathe and smile, and a few days later, I did see a solution. I knew that the only way I could die peacefully would be if I were reborn now in others who wished to do the same work. Then my aspiration could continue even if this body of mine were to pass away. I thought about the young people who came to practice mindfulness with Thay, and I decided to share with them my experiences and deepest desires about helping suffering people. I would teach them how to choose medicines, how to wrap parcels, how to write personal letters to the poor, and how to keep Western people in touch with the suffering of the Vietnamese people. Under my guidance, a few young people were inspired to start their own committees for hungry children. With those who wanted to do my work in the West, helping those who suffer a lot in their minds, I asked them to join the Plum Village Sangha, to be trained as a monk or a nun, like me, trying to live in peace 24 hours per day with those who are very different, so that in a few years, they will be able to listen to the pain of others and try to help. If I die tonight, by a car accident or a heart attack, these 38 small groups working for hungry children, my 38 incarnations and these young monks and nuns-my continuations--will allow me to die in peace. If tonight my heart ceases to beat, you will see me in all these sisters and brothers-those who enjoy my work for hungry children, those who enjoy my work of listening to the suffering of people in order to help them be healed. You can see my smile in their look and hear my voice in their words.

Whenever I do anything, I see the eyes of my parents and grandparents in me. When I worked with villagers, I always had the impression that I was doing the work together with them and also with the loving hands of those friends who saved a handful of rice or a few dong to support the work. My hands are their hands. My love is the wonderful love of the network of ancestors, parents, relatives, and friends born in me. The work I do is the work of everyone. Even now, I can see that I am already reborn in many of my young sisters and brothers, and in many of you too, who continue my work.

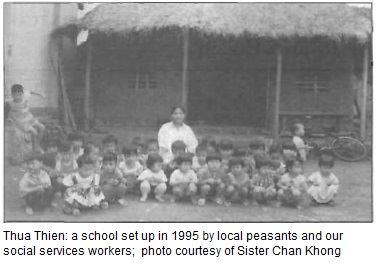

Sister Chan Khong, True Emptiness, is a nun living in Plum Village. She has been Thich Nhat Hanh's associate for over thirty years. This article is excerpted from Learning True Love (Parallax Press). She continues her humanitarian work in Vietnam. (Please see The Mindfulness Bell, Issue 21.) Since Spring 1998, seven new self-help villages have started: four in Phong Dien, Thua Thien Province, one in Suoi Bac, one in Ba Ria, and one in Lam Dong.