Part One

By Lori Zimring De Mori

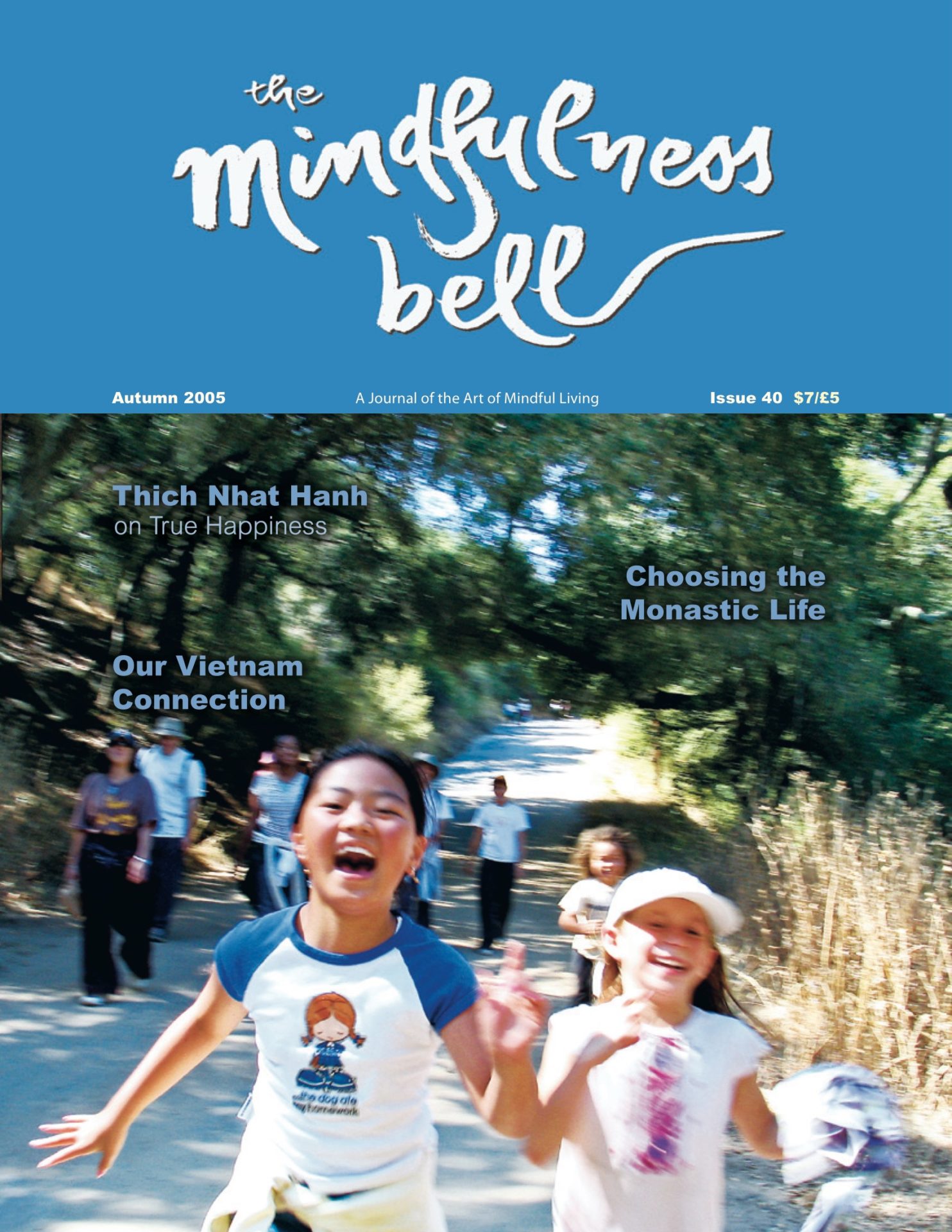

On a quiet summer morning in the French countryside near the village of Thenac, several hundred people sit patiently in the boxy, light-filled room which serves as Upper Hamlet’s main meditation hall in Plum Village. Children are at the front—some squirming, some with their heads in a parent’s lap, a few sitting still and straight as little Buddhas-to-be. The rest of us are crowded onto cushions,

Part One

By Lori Zimring De Mori

On a quiet summer morning in the French countryside near the village of Thenac, several hundred people sit patiently in the boxy, light-filled room which serves as Upper Hamlet’s main meditation hall in Plum Village. Children are at the front—some squirming, some with their heads in a parent’s lap, a few sitting still and straight as little Buddhas-to-be. The rest of us are crowded onto cushions, meditation stools, and chairs which spill out of the hall into the summer sunshine.

Monks and nuns begin to file in from opposite sides of the room. They have the shorn heads of those who have renounced the material world in favor of a life of the spirit, and walk in the measured, unhurried way of those who have spent a lot of time with Thich Nhat Hanh—utterly without false piousness, but as if every step were the final destination. Their robes are the warm brown color of loamy soil and hang straight from their shoulders to the ground.

They assemble themselves into several rows, monks on the left, nuns on the right, facing us and holding song books. Everything about their dress and demeanor expresses the intention to de-emphasize the self-absorbed “I” whose hungry ego obsesses with the mundane vanities of fashion, hairstyles, and superficial beauty. They look composed though not solemn; cheerful but not chatty; eminently likeable and unintimidating. Some of the nuns have covered their heads with brown kerchiefs knotted at the nape of the neck. A few monks wear woolly brown caps. Mostly there are bare scalps over bony skulls. And faces. Western ones, Asian, some wizened and a great many fresh and smooth as plum skins.

I find myself studying them carefully. I’m trying to imagine what they were like before they’d taken their vows, when they were living in the world like the rest of us. Wondering what made them leave that world for one of silence, service, and vigilant mindfulness.

A bell rings clear and high, like a single note from a songbird. We scramble to our feet as the Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh enters the room. He seems to move in slow motion, or as if he were inhabiting some other dimension (or more likely, fully inhabiting this one)—and his gaze, should you happen to catch it, is a compelling mixture of vibrancy and stillness, so alive as to be startling.

Thay embodies the Buddha’s instruction to “make of yourself a light.” He combines the moral authority of Gandhi and Martin Luther King with a resolute steadfastness of purpose and unwavering patience and kindness. His impeccability as a teacher and a human being is inspiring, and more than a little intimidating. There is still so much work to do—so many habits of mind to recognize and transform; so many petty thoughts, self-obsessed fears, and hollow vanities to let go of; so many ways to be more kind, more patient, more generous.

Thay sounds the bell and the monastics begin to chant the Heart Sutra in Vietnamese. Some sing phonetically from song books, others from memory, but all of them know the words by heart in one language or another. In English the chant is slow and melodic, one word flowing into another in a river of sound. This version is deliberately monotone, each syllable distinct and staccato, rhythmic as a chisel hacking away at the rough husks around our hearts. “Listen Shariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form. Form is not other than emptiness, emptiness is not other than form.” What does this mean? The words are plain enough but to gnaw on them with the everyday, rational mind yields little or nothing. I imagine they can be understood with the wisdom mind—the “heart mind” that looks courageously into the true nature of things, and is nurtured by a steady diet of mindfulness and compassion. Thay calls this “watering our seeds” of kindness, compassion, and mindfulness through how we walk, eat, listen, speak, consume (or don’t), do virtually anything and everything. It seems a good way to live well. If an understanding of emptiness eventually comes with it, all the better.

The next chant is a heartfelt wish for happiness: “May the day be well and the night be well. May the midday hour bring happiness too. In every minute and every second may the day and night be well.” The words wash over us like blessings and we lap them up like hungry puppies. In any other context the world-weary cynic in me might reject the chant’s simplicity of expression. But somehow these voices, this place, and our shared aspiration to live life as a conscious journey make it feel as if our efforts actually could generate happiness. Not the impossible happiness of a life without pain or loss or disappointment, but the happiness that comes from being open to this life, at every moment, whatever it has to offer.

Coming from the monastic community the words have an added potency. We spend our days with the nuns and monks—both inside and outside the meditation hall. We share meals, conversations, slow morning walks to neighboring hamlets, and cups of tea. There are little moments—waiting in line for a meal, beginning to eat, washing dishes—when I can tell they are reciting gathas, the short mindfulness verses that help bring awareness to even the simplest actions. But they also run (barefoot, robes flying) after soccer balls with the teenagers, strum guitars and bang out rhythms on African drums, rehearse plays with the kids, and wrestle with sophisticated sound and computer equipment.

Their generosity towards us has a quality of effortlessness to it. Their practice doesn’t feel dogged or forced. To put it simply, they seem happy and joyful—not in some sort of mystical, blissed-out way, but in a most ordinary one. On some level this surprises me. I’d always thought of monastic life as requiring a noble and unnatural giving up of things: ego, wealth, possessions, sex, marriage, children. I’d expected there to be at least a whiff of teeth-gritting renunciation; a spectral air of deprivation; something other than the bright radiance of people whose lives seem to agree with them.

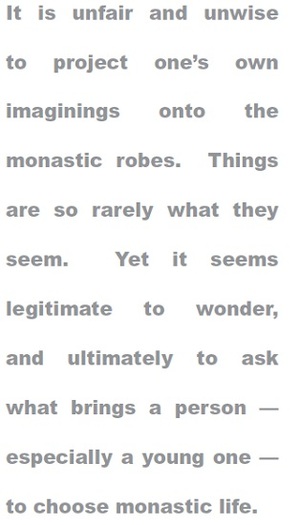

It is unfair and unwise to project one’s own imaginings onto the monastic robes. Things are so rarely what they seem. Yet it seems legitimate to wonder, and ultimately to ask what brings a person—especially a young one—to choose monastic life over the “go-to-college-get-a-job-get-married-raise-a-family” paradigm that propels so many of us. I posed the question to four young monastics—two I’d met on retreats, two I hadn’t known at all. What I found were four unique human beings whose individual life paths have intersected in a place called Plum Village. These are their stories.

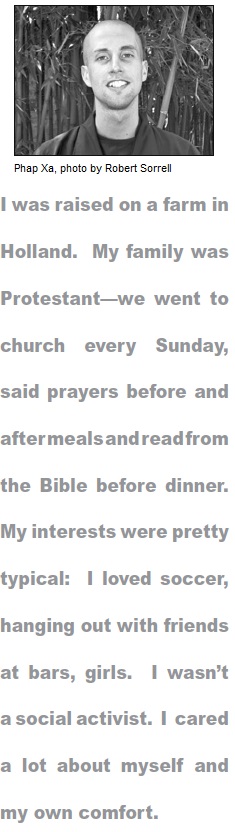

Phap Xa

Phap Xa came to Plum Village from Holland and took his monastic vows in 2002. He is twenty-nine years old, tall and lanky, with clear green eyes and an angular face brightened by a great, flashing smile. Like all monks ordained by Thich Nhat Hanh he carries the name Phap. Xa—“equanimity” in Vietnamese—is his given name. “Thay gives us the name he thinks most suits us. It is meant to be a door to practice, either reflecting a quality or pointing to one to be developed.”

How does one become a monastic in Thich Nhat Hanh’s order?

You can’t just show up at Plum Village and ask to ordain. First you practice with the community. If you decide you want to ordain you write a letter to the Sangha saying that you aspire to become a monk. The community meets to consider whether they feel you would succeed as a monastic. If the answer is yes, you become an aspirant and live—together with other aspirants—with the monastic community for at least three months before ordaining.

Did you always want to be a monk?

[Laughter] No! It feels like my decision is a miracle. While growing up I never imagined I’d become a monastic. I was raised on a farm in Holland. My family was Protestant—we went to church every Sunday, said prayers before and after meals and read from the Bible before dinner. My interests were pretty typical: I loved soccer, hanging out with friends at bars, girls. I wasn’t a social activist. I cared a lot about myself and my own comfort.

The shift was actually a very slow process. When I went to university I had to become more responsible. I started looking for a better way of taking care of myself, of facing difficulties. My older brother was practicing transcendental meditation. My parents weren’t happy about it, but the idea seemed interesting to me. When I was about twenty I became fascinated with Eastern thought and life—especially Taoism and martial arts. I began studying kung fu, moved on to tai chi and finally to chi gong. As I kept moving to softer forms of martial arts I was always inspired by my teachers’ way of living.

When did you begin meditation practice?

When I was twenty-five I started practicing Zen meditation with some other university students. I remember feeling strange and awkward the first time I sat. Eventually I wanted to practice formal zazen so I attended a sesshin with a Dutch teacher. My practice at this point was centered around sitting in groups and by myself. I was dedicated to it but I didn’t really have any Dharma friends.

What brought you to Plum Village?

I began reading Thay’s books—they made me want to practice with someone who had great authority. I came to Plum Village for a week. I was so happy on that first retreat. I shared a room with people who had come for three months. It inspired me that they made the time to stay. One of them had a book called Stepping into Freedom that Thay had written for monastics. I ordered it.

A year later I came back for another week. I was inspired by Thay’s writings about right livelihood and I began to feel that mine was “not that right.” I wanted my work to have meaning, to help lessen suffering or bring happiness. Working at an engineering firm wasn’t going to do that. I decided to return to Plum Village for three months in the spring.

What appealed to you about Plum Village?

The Sangha—the community of people practicing together. Thay was such a great inspiration and I looked up to him so much as a teacher but I also began to see that practice wasn’t only about a teacher. There is great value in a Sangha. I feel that what I can accomplish by living in a Sangha is so much greater than what I can accomplish by myself. Back home I felt alone in my practice and my life ideal. At Plum Village there were all these people with a similar life ideal, guided by the same teacher whom I love so much.

At what point did you decide to become a monastic?

During the first weeks of those three months my determination to practice became very strong. I’m a bit shy, but there was a Vietnamese Dutch monk I felt very comfortable around. I asked if I could speak with him, ask him a question. We found a quiet place to talk and I couldn’t remember what I wanted to say. He just looked at me and said, “Do you want to become a monk?” The question went straight to my heart. I knew it was what I had wanted to talk to him about and the feeling grew stronger every day.

How did your family react to your decision?

It was a very difficult time for them. I was so happy but my parents were skeptical and concerned for me. They thought the whole thing very strange and were not happy, not supportive. I returned to Holland for six long and difficult weeks, gave most of my belongings away and came back to Plum Village with only a few things.

Were you ordained right away?

No. Thay ordains monks two to four times a year. I lived at Plum Village for six months before being ordained as a novice. As novices we take ten precepts. At full ordination (three years later)

monks take 250! The people you ordain with are like a family. There were eighteen of us all together—thirteen brothers and five sisters. As aspirants we were each assigned a Dharma teacher to mentor us—mine was the Vietnamese Dutch monk.

How has life changed now that you have ordained?

Being ordained is like a rebirth. Monastic life has been very good for me. I’m a bit shy—I need time to feel comfortable with people, to create a space for myself to feel free. I’m beginning to feel more and more at home, to build relationships, to live harmoniously with the Sangha.

My doubts are less and less, and my practice has become deeper, more stable. My aspiration has always been strong, but at the beginning I was still ingrained with the ideals of happiness I grew up with: being successful, having a beautiful wife and children. For awhile I still had the habit of looking at women as potential partners but that has lessened. Now I feel a part of the Sangha—loved and supported by it like a family. I see more and more clearly that the life that was expected of me wouldn’t bring me the happiness that monastic life brings me.

Tue Nghiem

Tue Nghiem left Vietnam by boat with her family when she was nine years old. I first met her on a retreat with Thay in Rome where she helped run the children’s program. She is now thirtyfive years old and has been a nun for twelve years. My daughter was smitten with her playfulness, quiet wisdom, and lightness of spirit. We all were. Nghiem is the name carried by all nuns in Thich Nhat Hanh’s order. Her given name—Tue—means wisdom and understanding.

Were you raised a Buddhist in Vietnam?

Yes and no. My family was Buddhist but we didn’t practice the way we do here at Plum Village. We went to the temple on the full moon and every New Year. My older siblings were in a Buddhist youth group. I was the youngest of five kids. My father died when I was young but I grew up feeling very protected by my family. The values I grew up with were very much like the five mindfulness trainings given at Plum Village, but they were taught to us as life values rather than Buddhist ones. There was more faith than formal practice.

What do you remember about leaving Vietnam?

I lived in a big village about fifteen kilometers from Hue. There was a lot of fear and uncertainty—people’s freedom was restricted, their property taken, education had become an indoctrination in Communist thought. Many people left by boat—they left because they felt there was no future. My family wanted us to have one.

We went on my uncle’s boat. I didn’t know we were leaving. I was only told I had to go somewhere with my sister. The rest of the family split into groups and left the village in different directions. We met in a remote seaside village that night. When I saw the rest of the family I was afraid. They were acting so secretive. We had to hide under bushes and not say a word. A man helped us onto the boat. By the way my oldest brother hugged him I knew we weren’t coming back.

There were about twenty of us on a small open boat, a third of us children. We were on it for a week. I wasn’t sad—it felt like an adventure, but I could sense my mother’s fear. We arrived in Hong Kong and lived in a refugee camp for a year. I loved that time—we were all crowded together having fun, playing.

Where did you go from Hong Kong?

My uncle asked a Protestant church to sponsor us to go to America. A couple from Oregon sponsored us—when I went back to Vietnam for the first time in 1999, they came with me. We went from Oregon to Stockton where we had family. My mom worked on a farm and took English classes in the evenings. I started school in the ESL (English as a Second Language) program. I was a good student so I was transferred to the regular English classes. I wasn’t happy because I didn’t understand English and my friends were still in ESL, but I felt I was in school for a good purpose and I studied hard and ended up enjoying myself.

Did you have any sort of religious practice at that time?

There was a network of Vietnamese temples in Northern California. In Stockton we went to the temple every weekend. It was not so much a place to practice as a place to connect to our roots. There were Buddhist youth groups at the temple where young Vietnamese kids would come to learn the language, history, and Buddhist teachings.

When I was fourteen I went on a one-week Buddhist youth retreat and met Thay. Watching my breath, walking slowly, the idea of being mindful was all very new to me. At the retreat I felt like I wanted to live in that way—though not necessarily as a monastic. For the next few years three friends and I would spend our summers living at the temple in Stockton. I realized that before I hadn’t really been suffering but I was a bit lost, had no path. Adolescence was difficult—my mom supported me with all her heart but she didn’t really know how to help me understand what was going on with my body, my mind, school. I was balancing two cultures and not completely accepted by either.

Why did you feel you weren’t accepted by the Vietnamese community?

The problem wasn’t with my friends—they were mostly Vietnamese from the Buddhist youth group and temple. The conflict was between the Vietnamese who arrived in the states as adults and those who arrived as kids. We were the first generation of boat people to go to college. They were traditional, had a restrictive view of women, and thought many of us were too Americanized. I was young, playful, loud, and outspoken—and I was going to the University of California at Davis to study psychology and education. I was criticized because I was going to college. They felt I thought I was better than they were because of my education.

I stopped going to the temple because I no longer felt supported there. I decided I wanted to work with problem kids from Southeast Asia. I took an internship where I counseled kids who were having difficulties. Sometimes I’d go to their houses to meet with the parents. There was a tremendous culture, language, and generation gap between the parents and their children.

What brought you back to practice?

In my second year of college my brother became a monk (instead of going back to college to get his masters as he had planned). He didn’t tell us until he had already taken his vows. My mom and sister were so upset. They’d dreamed a dream for him which he wasn’t going to live.

When I graduated from college my brother sent me money to come to Plum Village for a month-long retreat. For the first time I felt so at home. I’d never felt like that before. My brother wanted me to come back with my mom for a three-month retreat in the fall. We did. Thay was teaching Buddhist psychology. I learned so much—so much more than I’d learned during my years at college. At college it felt like what I’d studied had nothing to do with me. These teachings felt so deep. So related to me. I was finally learning how to take care of my own emotions and I felt I could be so much more helpful counseling kids if I had a better understanding of myself. I liked the practice so I decided to stay at Plum Village—as a layperson—for the year before starting graduate school.

What did you like about the practice?

The sutra that really struck me was the Establishment of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness—body, feelings, perceptions, and objects of mind—the Satipatthana Sutra. I thought, “It can’t be this easy. It can’t be the Buddha who said this. It must have been Thay.” Of course it wasn’t, but because Buddhist psychology was so much more complicated, I couldn’t imagine that these simple, straightforward teachings also came from the Buddha.

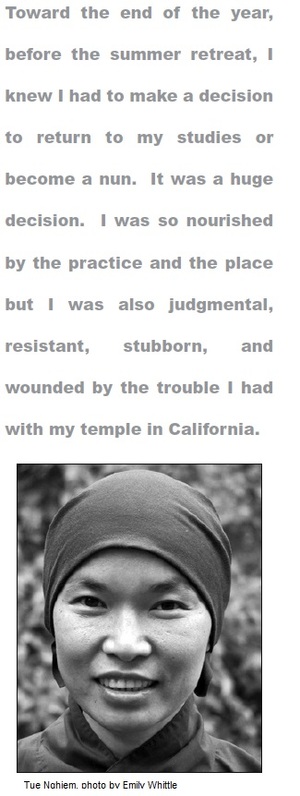

When did you decide to become a monastic?

Toward the end of the year, before the summer retreat, I knew I had to make a decision to return to my studies or become a nun. It was a huge decision. I was so nourished by the practice and the place but I was also judgmental, resistant, stubborn, and wounded by the trouble I had with my temple in California. The nuns—there were only five of them at that time—were very supportive. So was my brother. During that year at Plum Village we would bike, take hikes, and talk. He helped me overcome my resentment.

I made the decision to become a nun only after I left Plum Village. I chose this path so that I could be myself, accept myself as I was and grow from there, never being discouraged simply because I was a woman. When I returned to the States I was struck by the amount of consumption I saw, the carelessness towards the earth.

That October Thay taught a retreat at a Vietnamese monastery in California. My brother was with him. One afternoon I was having tea with Thay and I just blurted out, “Thay, I want to become a nun.” He didn’t say anything! After awhile he said, “Look at the sunset.” When my brother and another monk came in Thay sent us off to have dinner. I didn’t know if his answer was yes or no. I almost wished it was no. It was very scary—I felt like I was swimming against the stream. I returned to Plum Village in November—not knowing if it was to become a nun or stay as a layperson.

Three friends picked me up at the train station. They gave me a hug and I knew Thay’s answer. We all ordained together. We are so much closer now as monastics than we ever were as lay friends. I feel tremendously supported by them.

Was the transition from layperson to monastic difficult?

In a way. I had extremes of emotions, a strong, outspoken personality, and a lot of resistance to the idea of conforming. I’d do little acts of defiance—wear bright socks, mix the colors of my robe and pants, knit myself a colored hat. I was afraid of losing my identity, of not being unique anymore. I liked the practice though—sitting, walking, working wholeheartedly—and everyone was supportive.

And now?

I’ve realized I can never be like anyone else. The idea of conformity was an illusion. It doesn’t matter anymore how I look on the outside. Who I am is so much more than how I wear my clothes or what people think of me. I’m happy. My happiness used to be so dependent on exterior conditions. I couldn’t find it in myself. Now I feel a kind of inner path—my own—not even created by Thay. Seeing that path brings me a happiness not so dependent on exterior things. There is a continual sense of understanding and self discovery. Even now. Always.

I don’t know where I got the courage to become a nun. I’ll never regret the decision. It’s funny. I never wanted to have my own family and kids—my dream was to have a small house with lots of trees, take care of my mom (who is a lay resident at Deer Park in California) and have lots of friends over on weekends. In a way, that’s what I have here at Plum Village.

You’ve become a Dharma teacher by the Lamp Transmission. What does that mean?

The Lamp Transmission—given five years after full ordination—is one of the deepest ceremonies. All the elders are there and Thay officiates, but he is really holding the ancestral energy and passing it down. At the ceremony we give a short Dharma talk and are encouraged to fulfill the role of teacher, to be a lamp, a light to all beings.

Do you like teaching?

I’m nervous if I speak from my intellect, but if I speak from what Thay calls the store consciousness—from deep knowing— then teaching and sharing become easy. You feel lighter when you speak. Your ego is not involved. I think that is how Thay speaks.

Lori Zimring De Mori, Integrated Awakening of the Heart, lives with her husband and three children in Tuscany. She is a food and travel writer.