By Dr. Larry Ward, Kaira Jewel Lingo in October 2004

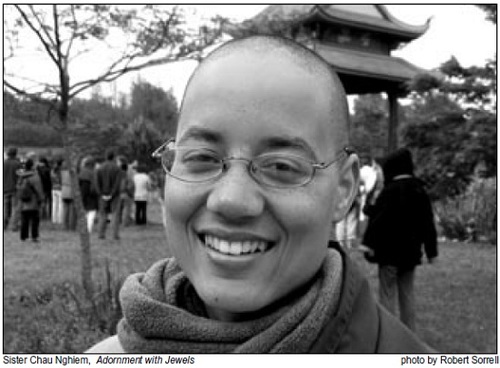

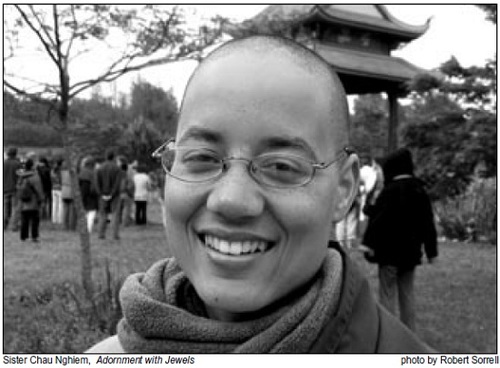

Larry Ward Interviews Sister Chau Nghiem June 20, 2004 at the New Hamlet, Plum Village

Sr. Chau Nghiem, can you give us a glimpse into what it was like being a person of African American and European American descent, prior to coming to Buddhist practice and monastic life?

By Dr. Larry Ward, Kaira Jewel Lingo in October 2004

Larry Ward Interviews Sister Chau Nghiem June 20, 2004 at the New Hamlet, Plum Village

Sr. Chau Nghiem, can you give us a glimpse into what it was like being a person of African American and European American descent, prior to coming to Buddhist practice and monastic life?

It’s been at the center of my searching all my life. I have always tried to understand who I am, because from a young age I felt that there were conflicting parts of me. My life has been very complex and very rich because of this.

I was born in Chicago and grew up in a large, Christian, lay residential community. My mother is African American and my father is European American. There were other African Americans in the community, as well as Indians and Asians, but it was mainly European Americans. The neighborhood surrounding us on the north side of Chicago was very diverse.

When I was eight or nine, I would squeeze the bridge of my nose a lot, hoping it would become skinny like a white person’s, because somewhere I got the message that my nose was too flat. Also, my brother and I met my dad’s parents for the first time when I was nine, after my parents had divorced. It was only after my parents divorced that we were allowed to come visit them in Houston. And they had an African American maid. So that was a very stark message and it stuck with me.

But from age eight to twelve we also lived in Kenya. It was very good to live outside of the United States, which has unique racial practices. It was wonderful to live in an African country, to go to school with many African children, and to grow up in an environment where people lived simply and close to the land. Visiting the homes of my Kenyan friends, I learned some of their native language and culture. Near our home, there were always women in their beautiful, colorful kangas, selling things in the market. Something deep in me was nourished.

I went back to Chicago for junior high, and was bussed to a racially diverse school on the South Side. I had Latina, Polish, Asian, and black friends. But being different racially wasn’t something we talked about or were really aware of, I think because we hadn’t started dating yet. It all gets complicated when you think, Who am I going to date? Race wasn’t on my mind, and I didn’t see myself as a person of color or as a person of a certain race.

But when I started high school, we moved to Atlanta. I lived with my dad and his fiancée, who were both white, in an all-black neighborhood. I attended a mostly white school. So suddenly, I was out of the lay residential community that I’d grown up in all my life which had been a cushion between me and the world I now found myself in. It began to get really hard, with no other racial groups but whites and blacks, and all this Southern history embedded in the culture.

It became clear that I didn’t fit with the black folks. I’d grown up in different parts of the world, but mostly with white people, so I didn’t talk like a black person. I didn’t have the same mindset or family background. I could dance! I could always dance, but otherwise I didn’t fit in. There were other kids who were biracial: black and white, and we all had to try really hard to prove that we were black. It was very painful.

I think not growing up with my mom also made me feel like something was missing. My parents divorced when I was seven and my brother and I lived with my dad. We only visited my mom and her relatives for two weeks every summer so I never really lived with black people. I was hungry for something they had that I felt was my inheritance, but that was somehow foreign to me.

Around that time I started to read a lot of African American authors. My dad always had us listen to many kinds of music, but especially to soul music and R&B. This cultural connection to my ancestors spoke to me on a very deep level, and helped me make sense of things.

In high school it became clear that I did belong to a certain color, and that was black. I took that on, and said, “I have a white father, but I am black, because that’s what society says I am.” So I dated mostly black men and checked the African American box on official forms. But I knew that the boxes I checked and the messages I was receiving did not fully describe who I was.

In my junior year of high school, I wanted to spend a year abroad as an exchange student and I chose Brazil. I wanted to experience being in a society where the lines of racial discrimination were less rigidly drawn and where people interact with other races with more humanity and ease. The African Diaspora became the focus of my academic interests. I learned capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art. My master’s thesis in university was on capoeira as emancipation practice for African American young people. A major concern of mine as a teenager and young adult was to understand and help to change the suffering caused by racism that I experienced and witnessed around me.

What was the purpose of the People of Color Retreat?

For me it was to embrace people of color, to reach out and say, “Hey, you! We want you to feel like this is your space, too.” It was motivated by a deep wish to help people feel at ease. Like our other retreats which focus on a group of people with a common life experience (i.e., police officers, congresspeople, children, artists, psychotherapists, etc.), we wanted to provided one more condition to help people feel safe and bring mindfulness into their lives. Sometimes you have to open lots of doors; this was just opening one more door. Also many of the monastic brothers and sisters felt that in order to be complete as a community, we needed to reach out to a wider group of people, to include a missing element in our Sangha.

Who attended the People of Color Retreat? What were we like and where were we from?

The first night in the front of the Dharma hall, looking at the sea of colored faces, I could have cried. It was so beautiful! Mainly we were from the United States, many of us coming for the first time to this practice, and many who were new to Buddhism. Many were also from the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender communities. The two biggest racial groups were African American and Asian American, although most people had quite a mixture in their backgrounds. There were also Latinos and Native Americans, and a few European Americans.

Why has it taken so long to introduce this practice to people of color?

Actually, I think a majority of Buddhists in the United States are people of color: they’re Korean Buddhists and Chinese Buddhists and Japanese Buddhists. They are mostly in insular communities that are preserving a tradition.

Another aspect of Buddhism is influencing mainstream American society. When we become Buddhist practitioners it’s difficult not to reflect in our Sanghas whatever racial blindness we carry. If we live in a white neighborhood with white schools and primarily white work environments, of course our Sanghas will reflect that. There are also economic obstacles. But the number of practitioners of color is definitely growing. A hundred people attended the African American Buddhist retreat at Spirit Rock in 2002. This year at Deer Park there were almost three hundred.

What was the biggest challenge in the organization and development of the retreat?

For me the biggest challenge was defining the terms of inclusiveness. How do you handle requests from people who aren’t of color but who want to come? How do you design a Dharma discussion where people of color feel at ease, and also include our forty white monastics? At first we felt the retreat should be for people of color only, but Thay suggested that while priority could be given to people of color, European Americans could still come if there was space.

When we began to reach our maximum capacity, I had to turn away white people. Some felt that they were being discriminated against and were hurt. The monastery is usually open to everyone, so being a person of color and having to explain to a white person that they can’t attend was quite painful. I told one person he couldn’t come because we had to save the last spaces for people of color and he said, “Well, white is a color!” I wrote him and said, “White is a color, but white is not the color that is undergoing racial oppression in this country.” I sent him some concrete statistics on the racial discrimination happening here. Several other cases were not easy to resolve. How do you determine who is white or of color anyway? Some people look white but have ancestors of color; who are we to say they are not people of color? These difficulties illustrate how people of color often spend so much time thinking and worrying about what white people feel and think. It’s not a helpful habit energy to always see ourselves through the eyes of white people. In the end, retreatants were happy that the majority of people were of color and asked that future retreats have the same ratio.

There was so much karma coming at me at the registration desk! It was difficult to feel like I was taking sides but at the same time trying to offer people of color the safe and supportive environment they needed. I don’t know how to be fair and compassionate all the time.

Next time there should be at least three people to help with registration, for greater collective insight into such situations.

For me just to talk about “them” and “us” and “white people” and “people of color” is painful. Since becoming a nun, I don’t think about my European and European American brothers and sisters as white, I just see them as my brothers and sisters. But in this retreat full of people of color, I felt an incredible joy and glory in myself being a person of color; it was profound and healing. I had never been around that many people of color practicing mindfulness.

How has the practice been helpful to people in dealing with their suffering?

It was so important for people to hear that Thay understood and shared their difficulties. In his orientation, he talked about his struggle for peace in Vietnam, his connection to Dr. King, and his own experience of being discriminated against. He told of being detained at the Seattle airport in the 1960s when he was on tour speaking out against the war in Vietnam. Because he did not have a transit visa, immigration officials seized his passport and locked him in a room with big “Wanted” posters on every wall. Thay was telling us, “I’ve been there. I’ve been through what you have experienced.” And people felt, Ah! Okay. I’m not going to be preached at by someone who doesn’t know where I’m coming from. Here’s someone who has been where I am and has reached a very beautiful place in spiritual life. So I don’t have to be stuck.

Usually when we have a transmission of the Five Mindfulness Trainings, Thay puts the incense on the Buddha altar and gives the second stick of incense to a monastic to put on the ancestor altar. But at this ceremony, Thay offered incense to both altars. I think people really felt embraced and honored by Thay.

People also felt moved by the sense of community. For many, there aren’t other people of color they can share these concerns with in their local communities. Here we nourished each other, shared our common ancestry, and our desire to transform. We invited everyone to put an object connecting them to their ancestors on the ancestors’ altar. Someone brought a bag of rice, someone brought a book about slavery. Someone brought a T-shirt, with a picture of Indian chiefs that said, “Fighting Terrorism Since 1492: the Department of Homeland Security.” [Laughs.] There was a necklace, a bag of seeds, a doll. People brought pictures of their families, their ancestors, a drum. The last night retreatants shared a song or poem, or talked about their object on the altar. It was a highlight of the retreat: each sharing was so rich and nourishing. We were honoring and healing our blood family in the context of a spiritual family.

How can practitioners help increase access to Buddhist practice for people of color?

I think mainly it’s just to be open and not to feel like we’re doing anything wrong. When we bring up the idea of including more people of color in our Sangha, just to be aware of whatever feelings come up. It might be something comfortable, it might be uncomfortable. We have to be gentle with ourselves.

We need to talk about racism or discrimination like Thay talks about our painful mental formations: it’s a crying baby, and we need to take care of it. We need everybody’s mindfulness and insight because we’ve been running from it for a long time; we have to be careful not to be violent with ourselves, with our language; we need to have compassion for ourselves. Our attitudes about racism and discrimination are a transmission from our family and society. It’s thick, uncomfortable mud, but it can produce a lotus. We need to have a positive outlook.

Thay is so wonderful, setting the context of how we talk about racism in our practice of compassion and understanding. We also need to have curiosity and inquiry, not to assume that we know everything. We’ve been indoctrinated since birth, so we need a sense of spaciousness around our perceptions, being open to changing. We need to look into ourselves and to ask, “When did I start to identify as a person of a certain color, and how has that influenced my life? How do I act from that, in helpful and unhelpful ways?”

The history of racism in our society is so present, right under the surface; it doesn’t take much for it to come up. There’s little clarity or understanding about it. As a society, I see us going in the wrong direction; we’re becoming more stratified. We need a spiritual perspective on this collective suffering. Shining the light of mindfulness on this area of our lives will bring a lot of benefit. There are skilled people—you’re one of them, Larry—who know how to ask the right questions in a way that helps us to touch honestly the painful and scary feelings, and to see how to transform them.

For me this is totally about transformation and liberation, not about getting even or complaining or blaming. And it’s collective—we have to heal all of us. My five-year-old nephew is already being affected by racism. Already! He’s five years old, and I can see it. And I don’t want kids to have to live with that reality. This is about healing all of us, being compassionate with ourselves, and being willing to go where it’s not easy or comfortable.

What is emerging as next steps?

There is a five-day retreat for people of color planned at Deer Park in September 2005. The exact dates will be on our Website soon. The folks at Spirit Rock have asked Thay to lead an event in the Bay Area. People are excited, saying, “Come over here! Do some of that for us!”

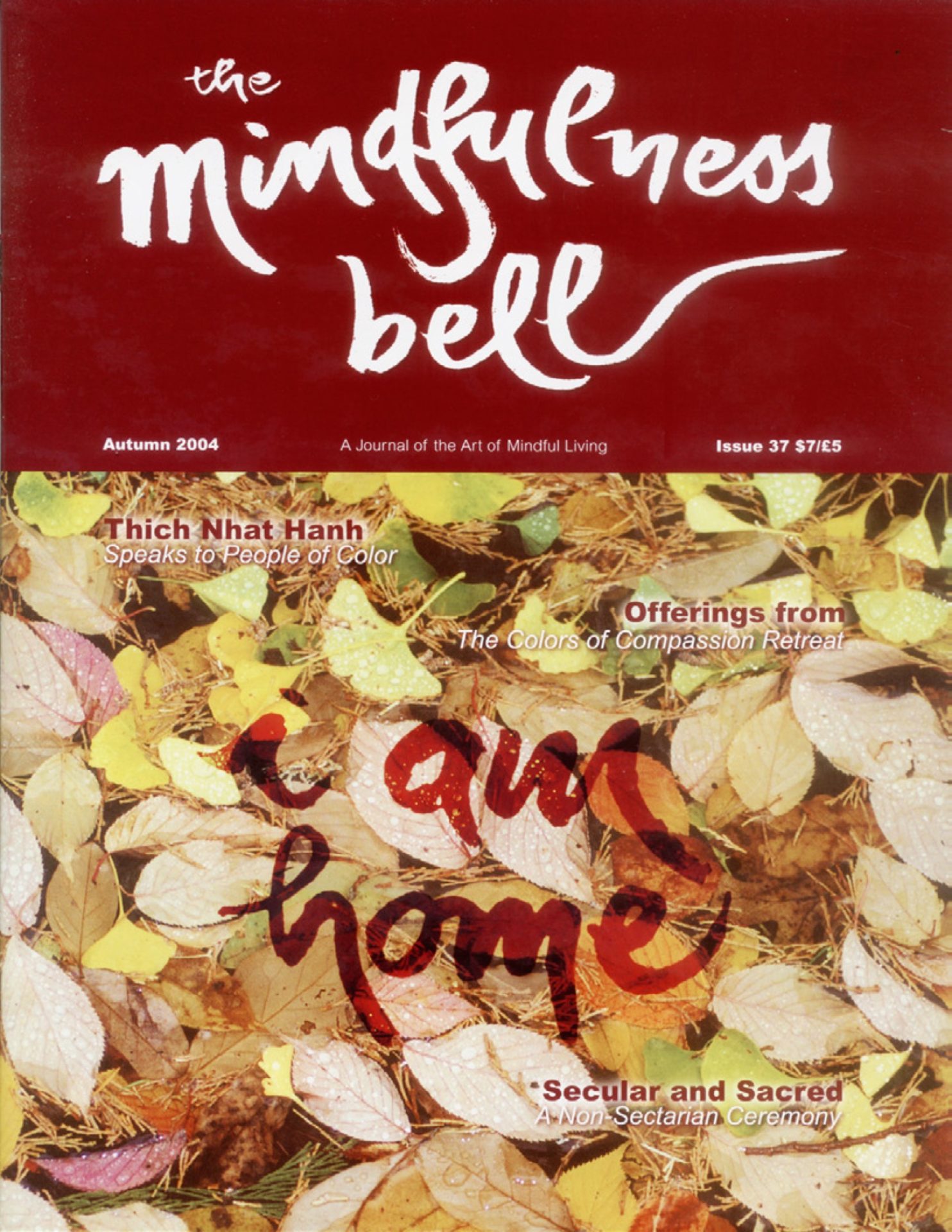

There is this issue of the Mindfulness Bell. Parallax Press is publishing a book this fall called, Dharma, Color, and Culture. There are plans to set up a self-sustaining endowment fund to help more people of color and other underrepresented groups to attend Thay’s retreats. We want to find ways to reach out to more young people of color. We are creating an group for people to dialogue about increasing diversity in our Sanghas (e-mail inclusivesangha-subscribe@yahoogroups.com to join in!). Trained people could come to local Sanghas or to our bigger retreats to lead us in how to unlearn racism and be more inclusive to people of color. I’d love to see our whole Sangha body engaged in a conversation about this.

I talked with a person of color from the UK who thinks it would be extremely helpful to have a similar retreat there. So this feels like a story I heard of an osprey who dove into the ocean for a fish, and picked up a whale. There is a lot of substance here to be worked with personally and collectively and globally. The inspiration of what’s already happened is starting to water positive seeds of healing and transformation in other places. Thank you for your interview.

Wonderful! Thank you, Larry. Thank you very much.