By Peter Matthiessen

In late March of 1991, on the way to a retreat for environmentalists to be led by the eminent Vietnamese Zen Master, poet, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh, I took time for a walk up Malibu Creek, in the Malibu Canyon State Park. Spring songbirds were numerous, and a golden eagle sailed high overhead, crossing the Santa Catalina Mountains of the Coast Range, and from a bridge over the creek I saw a heavy brown-furred animal half-hidden behind rocks close to the bank.

By Peter Matthiessen

In late March of 1991, on the way to a retreat for environmentalists to be led by the eminent Vietnamese Zen Master, poet, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh, I took time for a walk up Malibu Creek, in the Malibu Canyon State Park. Spring songbirds were numerous, and a golden eagle sailed high overhead, crossing the Santa Catalina Mountains of the Coast Range, and from a bridge over the creek I saw a heavy brown-furred animal half-hidden behind rocks close to the bank. From its striped ears, I knew it was a bobcat, stalking three coot that had come ashore into the sedges. So intent was it upon its prey that, moving out into the open, it looked back just once, the sun catching the oval of light fur around the lynxish eyes. However, the coot, sensing danger, swam away from shore, and as the bobcat made its way downstream, striped bobbed tail twitching in frustration, the slate gray birds with their ivory bills followed along, just off the bank, peering and craning to see where the wildcat had gone to.

The bobcat or bay lynx is not uncommon, but it is elusive, difficult to see; I have crossed paths with it perhaps eight times in 50 years of wildlife observation, usually as it crossed a trail or a night road. This was the first one I had ever watched for minutes at a time—ten minutes at the least—in open sunlight of mid-afternoon, scarcely 50 feet away, a stirring event that seemed to me an auspicious sign for the environmentalists' retreat that would begin that evening.

Originally the retreat was to take place at Ojai, but in recent weeks, due to housing complications, it had been shifted to Camp Shalom, a Jewish retreat camp in the Santa Catalinas, perhaps five miles inland from the coast; the camp lies in a hollow in the dry chaparral hills, in a grove of sycamore and live oak where two brooks come together. The hills were green and the brooks rushing from the heavy rains, which muddied the ground beneath the huge white tent and moved the whole retreat indoors.

My host was James Soshin Thornton, a student of Maezumi Roshi and the founding lawyer of the Los Angeles office of the Natural Resources Defense Council, which together with the Nathan Cummings Foundation, the Ojai Foundation, and the Community of Mindful Living, had sponsored the retreat. One of my own students, Dennis Snyder, was also present, and so were several environmental acquaintances and friends-of-friends.

Zazen, which took place in the meeting hall on the first evening, after some welcoming remarks by Thich Nhat Hanh, Joan Halifax of Ojai, and James Thornton, was a new experience for most of the environmentalists among the 225 retreatants, some of whom were later obliged to move to chairs, but they persevered bravely and by the week's end, were sitting as assiduously as all the rest.

"When you take care of the environmentalist," said Thich Nhat Hanh, urging the use of a gentle smile to help us pay attention to each moment, "you take care of the environment." This remark might have been the theme of the whole retreat.

Thich Nhat Hanh is a small, large-toothed man with a broad smile and kind, smiling eyes, so youthful in appearance that one scarcely believes he was nominated in 1968 (by Martin Luther King) for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In his first Dharma talk next morning (on Breathing Meditation: "When I breathe in, I am aware of my eyes . . .of the lovely morning . . . of my heart... ") he stood in brown robes in the early sun that shimmered from the small hard shiny leaves of live oak and poured through the windowed wall behind him, filtered by a lovely wooden screen of six carved panels that Joan Halifax believes came originally from China. Like chinks of sun through the brown rosettes of the screen, Thay's white teeth glinted in that child-like wide-eyed smile.

"Sometimes we believe we would like to be someone else, but of course we cannot be someone else, we can only be ourselves, and even that is very difficult.... To be ourselves, we must be in the present moment, and to be in the present moment we must follow our breath, be one with our breath, for otherwise we are overtaken by emotions and events...."

Thay's daily talks were pointed up by intermittent bell notes rung by his attendant Therese Fitzgerald (formerly of San Francisco Zen Center), and all meals, eaten in silence, were also punctuated by a bell, to remind retreatants to pay attention to this present moment.

Insight depends upon awareness of this moment, according to Thay's teaching, which leads inevitably to compassion and a natural state of being. His teaching returns again and again to the soft image of a flower, "showing its heart" as it opens to the sun. The mudra of gassho he likens to a closed lotus, the hands opening outward in gratitude and thanks for this extraordinary being, in the way that a bean sprout opens, smiling, to the sun and wind. That half-smile on the lips will lead to real, unforced well-being, contributing to a sincere joy in one's practice—"if your practice is not pleasurable—then some other practice might be more suitable," says Thay.

On the first evening, an informal panel—Thay's associate, the Vietnamese nun Sister Cao Ngoc Phuong, James Thornton, and Randy Hayes of the Rain Forest Action Network, also Joan Halifax and myself—took questions from the gathering of perhaps 225 persons that filled the meeting hall right to the walls. Sister Phuong, a small dynamic person who administers one hundred social workers in Vietnam (all unknown to one another, since they may be harassed by the government), was articulate and eloquent; like Thich Nhat Hanh, she counselled returning to the breath as the foundation of this moment, of our very being. And the panel agreed that in time of distress, we must go into that distress, deeper and deeper, become one with it.

On other occasions, in a sweet voice, Sister Phuong burst into song, manifesting the joy in this moment that Thay talks about. Discussing the anger she sometimes feels, seeing the waste of water and materials in our bathrooms and kitchens, she says she cures this by singing aloud, "When I go to the bathroom (kitchen, etc.) I feel happy, because I have learned to breathe deeply...." (After Thay's Dharma talk on the precepts, she remarked, "When you are truly mindful, you don't need the precepts.")

Each day began with two early periods of strong zazen, followed by recitation from the Sutras or, on one occasion, a fine letter to Thay from an environmental lawyer in the group who stressed the need for the spiritual base for environmental work that has been sadly lacking in most organizations. After silent breakfast in the dining hall, down along the creek, Thay would talk to us again, in a Dharma talk that one day ran close to two hours.

"We are only real when we are one with our breathing—our walking, our eating—and it is then that everything around us becomes r e a l . . . Eating a bean, be conscious of the true nature of that bean, the structure, all the non-bean elements that make up that bean, and permit it to exist. If you look into a flower penetratingly, you will see the sun, the minerals, the water that make up the flower, which contains all the non-flower elements in the world, just as a Buddhist contains all the non-Buddhist elements."

Thay's eyes sometimes remain sad even when he is smiling, and more than once during the week he expressed distress over the actions of President Bush in the Gulf War, which had almost deterred him from making his bi-annual visit to this country. He spoke to us of "sowing the seed of peace in our land," and attending to "the President Bush within ourselves . . . " as we might attend to our greed, ignorance, and anger.

"Take tender care of your anger, with mindfulness . . . don't suppress it . . . it is you. You have been watering the seed of your anger rather than the seed of your mindfulness; the anger comes from lack of understanding, and it comes very easily... If mindfulness is there, you are protected from anger and from fear."

And he spoke to us strongly against "sowing the seed of suffering" in our speech and actions. Another day, he pointed out our compulsive behavior, our inability to stop: the more we eat (sleep, telephone, watch television, drive in our car)—the more we fill the emptiness, in short—the hungrier we become. We must fill every moment, we cannot just to.

"How can we stop the arms race when we cannot stop ourselves?"

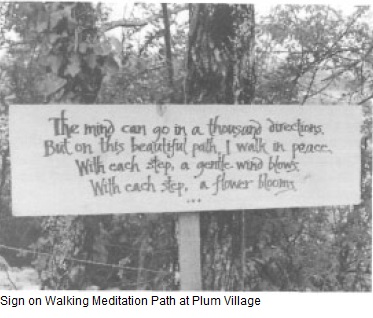

Following the Dharma talk came walking meditation in the hills, then lunch, then afternoon meetings with various leaders, late afternoon zazen, supper, and more evening meetings, followed by a last period of formal zazen. All of these events except zazen were interspersed by semispiritual musical presentations by two guitarist-singers, and an evening of entertainment was provided, and even a Passover supper, or Seder. At times, Thay appeared vaguely mystified by these secular events, which were not, however, permitted to alter the warm and yet serious tone of the retreat

Despite his gentle manner, Thich Nhat Hanh is a strict teacher with a strong adherence to the precepts. Talking informally one evening over green tea in his rooms, we discussed the fact that many if not most Zen teachers transgress the precepts in one way or another, and he said wryly, "They have the idea that that is all right for enlightened people."

He went on to describe his Rinzai training in Vietnam, where he became a monk in 1942 and founded the Tiep Hien Order in 1964; I had not realized that Rinzai Zen, which travelled eastward from China to Korea and Japan, then the United States, had also made its way south into Southeast Asia, where Hinayana Buddhism had held sway for centuries.

As the days passed and the rain ceased and concentration deepened, Thich Nhat Hanh's mild tones came and went like some wonderful soft voice from faraway in the mysterious stacks of a huge library. At times the whole brown-robed being seemed to shine, as if he and the sun-filled screen, the mountain light, were now all one. "We have to be a little bit mindful just to notice the moon, but we don't appreciate the intensity, the beauty of our life, until we are truly mindful in each moment."

Writer Peter Matthiessen is a Dharma successor of Bernard Tetsugen Glassman, Senseit and leader of the Sagaponack, New York Zen group. This essay was written for Ten Directions, the journal of the Zen Center of Los Angeles, and is used by permission.