Dharma Teacher Uli Pfeifer-Schaupp shares his practice in a former German concentration camp.

By Uli Pfeifer-Schaupp on

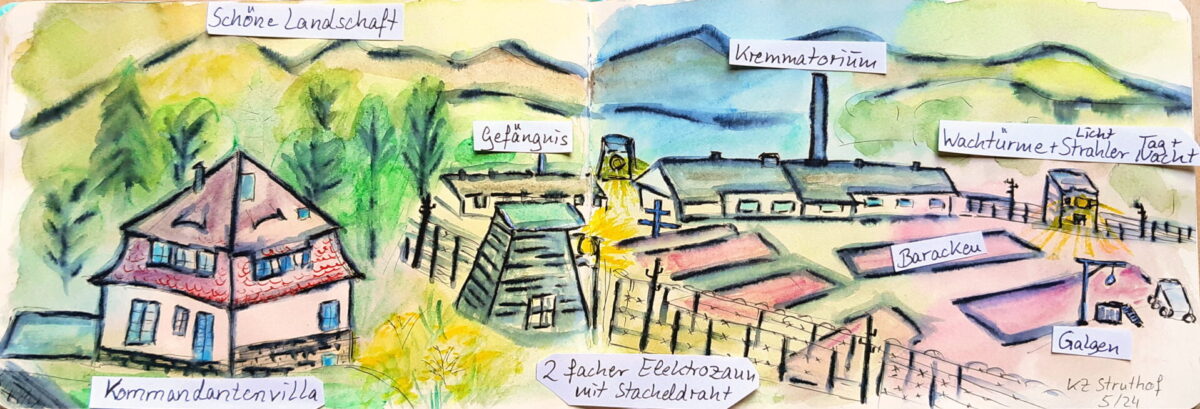

A magnificent landscape in the French High Vosges, fifty-five kilometers southwest of Strasbourg, at an altitude of over 1,000 meters, with a wide view over the Rhine Valley into Germany. This is where the French practiced winter sports before the Second World War and enjoyed the cool mountain air in the summer,

Dharma Teacher Uli Pfeifer-Schaupp shares his practice in a former German concentration camp.

By Uli Pfeifer-Schaupp on

A magnificent landscape in the French High Vosges, fifty-five kilometers southwest of Strasbourg, at an altitude of over 1,000 meters, with a wide view over the Rhine Valley into Germany. This is where the French practiced winter sports before the Second World War and enjoyed the cool mountain air in the summer, before the Germans annexed Alsace in 1940.

In the 1930s, a rare red granite was discovered in these mountains, which the Nazis wanted for their monumental buildings. This is why they had prisoners build a concentration camp here in 1941. There were seventy satellite camps of the Struthof concentration camp in the idyllic Black Forest and throughout Baden-Württemberg, Germany. A total of 52,000 people were imprisoned in the main camp and the satellite camps—people from Poland, Russia, Serbia, Croatia, Italy, the Czech Republic, France, Belgium, and Germany. Twenty-six thousand of them died or were murdered as a result of the inhumane working conditions. “Extermination through work” was the Nazis’ motto.

We stood in the former concentration camp in front of the ash pit next to the crematorium and heard the words of Thầy’s poem “Call Me By My True Names.” Here, they had an intensity that was almost palpable.

Eighteen people—almost all Order of Interbeing members and aspirants, sixteen Germans and two French—came together here for four days to practise together, to take steps towards peace on the “mountain of horror,” as it was called by former prisoners. We exchanged emails months in advance about how we could prepare for this difficult and, for many, frightening experience. And we had an exchange about our motivation two weeks beforehand via Zoom. It was already clear that the whole spectrum of experiences from the Nazi era would be present in this retreat: we are descendants of perpetrators, of victims, of people in the resistance, of “bystanders” and secret profiteers of the regime.

For the sharing at the beginning of the retreat, everyone brought an object that expressed their connection to the topic: a hymn book, a photo of a grandfather who resisted, a family book, the biography of a Jewish aunt who was able to flee to Switzerland in time to survive the Holocaust... With candles, a bell, flowers, and a picture of Thầy, an altar was created. It accompanied us through the days, and we gathered here again and again to share.

We spent the nights in a Friends of Nature house about twenty kilometers from the memorial. This distance was helpful for everyone and allowed us to take a deep breath and water the seeds of joy and gratitude during walking meditation in the evening.

As we walked through the camp gate into the barbed wire fenced area the next morning, we stayed close together as a sangha. The community proved to be a supporting element during these days.

Two stations characterized this day: first, a walking meditation through the steep camp down to the crematorium, holding the space there and bearing witness, and later on, meditating and chanting together at the towering memorial for the deportees who perished there.

On the second day, we completed our look at the victims and their suffering with a look at the perpetrators. We contemplated the commandant’s villa with a swimming pool right next to the camp’s barbed wire fence. We remembered the perpetrators, big and small, some of whom were our parents and grandparents.

Then we walked down the steep path to the gas chamber, which the prisoners also had to walk. It is now part of a “path of human rights.” This leads seventy-five kilometers to Rastatt, on the opposite side of the Rhine in Germany, where the memorial site for the democratic revolution of 1848 is located. On this path, we also remembered all the good things that grew out of this dark time, the lotuses that blossomed out of the mud: the end of the centuries-long hereditary enmity between Germany and France and the Franco-German friendship that grew after the Second World War through hundreds of town twinning agreements, sealed by a Franco-German friendship treaty. The founding of the United Nations in 1945, the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the creation of the European Union in response to the terrible experiences of the Nazi era...

Eighty-six Jewish people were murdered in the gas chamber. They were transported here from Auschwitz. Their skeletons were to be preserved in order to serve Professor August Hirth of the “Reich University” in Strasbourg and used as material to demonstrate the superiority of the Aryan race. We recited their names aloud together, which are engraved on a stone, and read the names of four homosexuals on a memorial stone next to it on behalf of all the other victims. We also read out the life stories of two of the victims to give them a face. A Jewish participant of the retreat recited aloud the names of her many family members who came from Warsaw and were murdered in Treblinka. Her father had only survived because he emigrated to Moscow before the Germans invaded Poland and then moved to Berlin with the Red Army.

The focus of the last day was a ceremony with the slightly modified text of the requiem that Thầy read out during his visit to Vietnam for the hungry spirits of those killed in the war in North and South Vietnam. It is a text of reconciliation and compassion that ends with the vow:

We vow that from now on, we will not allow our country, our continent, to go down such a path of injustice again. We will do our best to prevent people from being persecuted in our countries because of their race, their religion, or their political beliefs. From now on, we will no longer discriminate against anyone, use violence, or start wars. We will no longer use weapons to oppress, expel, and kill each other. From now on, we will use all our strength to build and maintain a democratic, free, and just society, so that we will be able to settle all differences of opinion peacefully. We will no longer resort to or incite violence against the women and men of our own country or against other nations.

It seemed almost unbelievable to us, but all participants of the retreat left with feelings of joy, gratitude, and healing. And we decided to continue on this path and organize retreats in other “places of horror” in the coming years to enable further steps of peace.