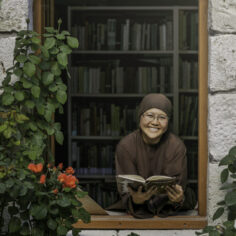

Sister Kính Nghiêm shares about recognizing and embracing suffering in yourself and your family.

By Sister Kính Nghiêm on

During the pandemic I had the opportunity, the practice of a lifetime, to go home and care for my parents for a whole three years. If you really want to test us monastics, our resilience in our practice, put us at home. It’s easy to be in the monastery;

Sister Kính Nghiêm shares about recognizing and embracing suffering in yourself and your family.

By Sister Kính Nghiêm on

During the pandemic I had the opportunity, the practice of a lifetime, to go home and care for my parents for a whole three years. If you really want to test us monastics, our resilience in our practice, put us at home. It’s easy to be in the monastery; everybody’s doing the same thing: breathing and smiling and letting go. But being at home all the time is like being in a pressure cooker.

It was very hard, especially because I had an expectation of having my own space. Sometimes I could be a little bossy about the practice. For example, saying you should not be eating while watching the TV, and those kinds of things. And one of the things that I realized in those years of practicing being confined, was not only taking care of my own emotions, but also my parents’ fear of what was going to happen next. I think there was collective fear for everyone surrounding the pandemic, and especially for my parents in San Diego, California, US. They didn’t speak English, and they didn’t know how to navigate everything, such as how to do their grocery shopping online. It was very stressful for them.

So I had to create my own space and also to hold them in that space. Eventually, we got along well. There were a few hiccups here and there, with some big hiccups. But we grew to understand each other better. I especially came to understand myself and how I react to certain things.

But there was one time when my mother was not feeling well, and I had to do a lot of things on top of monastery work, on top of family work, including navigating all the doctors, the paperwork, and everything else that went with that. So I was sort of running thin. I asked my father to help prepare dinner for Mom; all he needed to do was put food on a plate and heat it up in the microwave. As he filled the plate I said, “Oh, no, that’s too much. Mom doesn’t eat that much.” A very simple statement on my part. All of a sudden, my father put everything down, turned to the corner of the kitchen, held his head down low, and said, “You always tell me what to do.” At that moment, I saw my father’s five-year-old child in the corner, almost as if he was being punished. I thought, Where did this come from?

We can learn to embrace the pain and hold that space for ourselves, recognizing what has been transmitted from generation to generation.

I said, “It’s okay, Daddy. If you’re not ready, then I will take care of this. You just go sit and relax.” So I took the tray up to my mom and I told her what was happening. And she said, “You’re very much like your grandma.” I thought, Where did that come from? How did I become Grandma all of a sudden? And she said, “The way that you talk, you speak with conviction, almost like a sense of authority.” I know from my dad’s history that he was not loved by his mother, my grandma. Yet he always wanted to make his mother proud of him.

He was helping me, but somehow in his mind, he thought he was helping his mom. When I said, “That’s too much,” I saw this little boy that had let his mother down. So it became my practice to be his child, his daughter, and also to be the loving mother, the kind mother that my father never had. And that helped build the relationship: understanding where he was coming from. In those moments, I could react in a certain way and put this expectation on him like, “You’re my dad. Be my dad.” But at that time, I understood from my own practice that I became like my grandma without even knowing, and somehow I reminded my father of my grandma. I didn’t grow up with my grandma, so I didn’t know that I was exactly like my grandma.

In that image of my father, standing in the corner with his head hung low, I can see the deep pain that he held inside of him. The guided meditation [seeing my father as a five-year-old child] helps me to understand deeply without blaming him and without blaming myself. We can learn to embrace the pain and hold that space for ourselves, recognizing what has been transmitted from generation to generation.

We have so many things that have been transmitted down to us. And sometimes in this present moment, we think that we are that problem or we have this habit. And I don’t want to blame the past by saying “Oh, it’s their fault. They gave this to me, and now I’m like this, and this is who I am, and now I have to fix everything.” But in fact, I don’t think the teaching of awareness of suffering, the Four Immeasurable Minds, is to blame suffering for anything. Our habit is anything that we like to keep with us, and anything that we dislike, we try to eliminate it.

When we have a painful feeling and a negative seed arises inside of us, we do everything we can to get rid of it. But I have bad news for you. It’s going to be there. You can’t get rid of it! You can get rid of the idea of it, but it is still there.

Thầy said that when we recognize a negative feeling arising in us, we can hold it like a baby. We can smile to it, embrace it, and offer it comfort, because more than anything else, that is what our suffering needs the most.

Thầy said that when we recognize a negative feeling arising in us, we can hold it like a baby. We can smile to it, embrace it, and offer it comfort, because more than anything else, that is what our suffering needs the most. But instead, we punish ourselves for suffering, because that is our habit. I’m going to call you guys out on this one: We sometimes use meditation to punish suffering by saying, “Breathing in, I am calm. My suffering is not there. I relax my whole body, letting go of all these emotions.”

In that way, if we are unskillful, our meditation practice can become like spiritual bypassing. The practice of being 100 percent aware is not to bypass suffering. It is about being present for whatever comes to me. I establish myself in my own body, in my footsteps, and I ambe prepared to embrace what is., Iinstead of trying to breathe it away, I ambut being there 100 percent. (Or, for the beginners, 10 percent.) Being in our footsteps can help us to embrace ourselves, our suffering, and our despair. It’s not about learning the text or sutras, but instead, learning the sutras, but really establishing presence and not pushing anything away.

So now I’m more aware of when I become my grandma. And when I’m with my dad, I just say, “Good morning, Daddy,” and allow myself to be a child of my father. But I’m an adult, and on top of that, I’m a nun, and on top of that, I’m a Dharma teacher, too. So the pressure is high, and I have an expectation of myself that I need to be at my best. But really I can just enjoy being my father’s daughter. Because I have the practice, I can embrace that little girl inside of me. I can hold my father’s little boy’s hand and say, “Let’s do this together.” We don’t have to punish suffering or eliminate it. That is an illusion. Our practice is to simply accept suffering as it is and to help suffering understand itself. It also means to help us understand ourselves.

My father used to be a smoker. I guess for him it was a way to relieve stress. He is a victim of the Vietnam War and was also a soldier during the Vietnam War for the US side. He suffered a lot of fear, a lot of pain. He used to smoke as a way to forget things, because he didn’t know how to process all that he went through.

My younger sister didn’t like him smoking, because when you go to school in the US, you learn that smoking is bad; you’re going to get cancer. We were little kids and, we didn’t know any better. So my sister would take his cigarettes and hide them all the time. She would hide them in a little corner somewhere, and she would pretend that she didn’t do it. My dad got very mad at her one time, and he spanked her, saying, “You do not touch my cigarettes!” Of course, my sister cried. When he saw my sister crying, he realized that he had hurt her.

That day he made a vow to quit smoking, because it didn’t make him the person that he wanted to be. He became a victim of his own suffering, and he unintentionally transmitted it to his daughter. He has three daughters who became nuns. I don’t know if it’s a good sign or not, but I have two other sisters who ordained with Thầy.

Eventually my dad came to Plum Village, attended retreats, and meditated as best he could. One day, Thầy was teaching about Beginning Anew, and my father was a bit fidgety. There was something inside really bothering him.

He came to my sister and said, “I need to talk to you.” My sister was so nervous, thinking, “What happened? Why did Dad change? He never wants to talk to me.” She was a nervous wreck, really shaking. He said, “I really need to talk to you. I need to get this done now.” My sister didn’t know what to do, so she just had to sit there.

My father mustered up the courage to say, “I’m sorry.” And my sister said, “What?” He said, “I’m sorry that I hit you for hiding my cigarettes. And I never told you that I was sorry.” It took him fifteen years to get the courage to say that. And for my sister, it was awkward. In Asian families, we don’t hug and we don’t say, “I love you.” My mom was there witnessing this, and she said, “Just hug already!” because it was so awkward. And they hugged, and then my dad was like, “Okay, that’s enough.” It irks him to get emotional, but it was a breakthrough for him to be able to communicate his pain and suffering to his daughter. Sometimes as adults, we think, I’m supposed to know everything. I’m supposed to be okay. We don’t allow ourselves to be vulnerable because we want to be a good role model. Sometimes that can be a little bit toxic if we cannot model for our children how to communicate in a constructive way. It took my father fifteen years to apologize. We were being naughty, hiding his cigarettes. Little did we know that we had transformed him very deeply.

He never smoked again, and he has been clean for more than thirty years. That event really woke something up in him. But he could not communicate because he was so afraid of losing himself, losing the identity that he built of himself: I’m the father. I have this authority. I get to do what I want to do because I’m the adult in the house. And then if I say sorry, what does that make me? I’m no longer a person of authority or teaching. My father is a man of few words; I’m sure most fathers are. But sometimes he may feel very alone. Maybe we can all tune in to our father and say, “Daddy, I’m here for you.”

Now my father and I have a very good relationship. But the healing and transformation doesn’t just happen overnight. It’s not going to be fixed at the end of one retreat and everything is dandy. I’m warning you: this is just the beginning of a deeper transformation and healing.

It took my father fifteen years to say “I’m sorry” to my sister for something that had happened when she was five years old. We may forget the story, the details, the date, and the time, but we don’t forget the feeling. And I think that feeling sat with my father for so long.

Being 100 percent, establishing ourselves, gives us the energy so that we can come to face and embrace the things that come to us, whether they are in our present moment or from our past. That then will lay the foundation for how we will be in the future. So being 100 percent can heal us now.

This is an excerpt from a Dharma talk given on August 20, 2024 in the Assembly of Stars Hall and in the YMCA of Estes Park, Colorado, US during the Our Earth, Our True Nature Retreat. It has been edited for clarity.