Have you ever felt lonely or like you didn’t belong? Looking this way and that way for your “True home”?

Deer Park Monastery invites you to an international Online Retreat, At Home in the World, March 20-24, 2024. More details below.

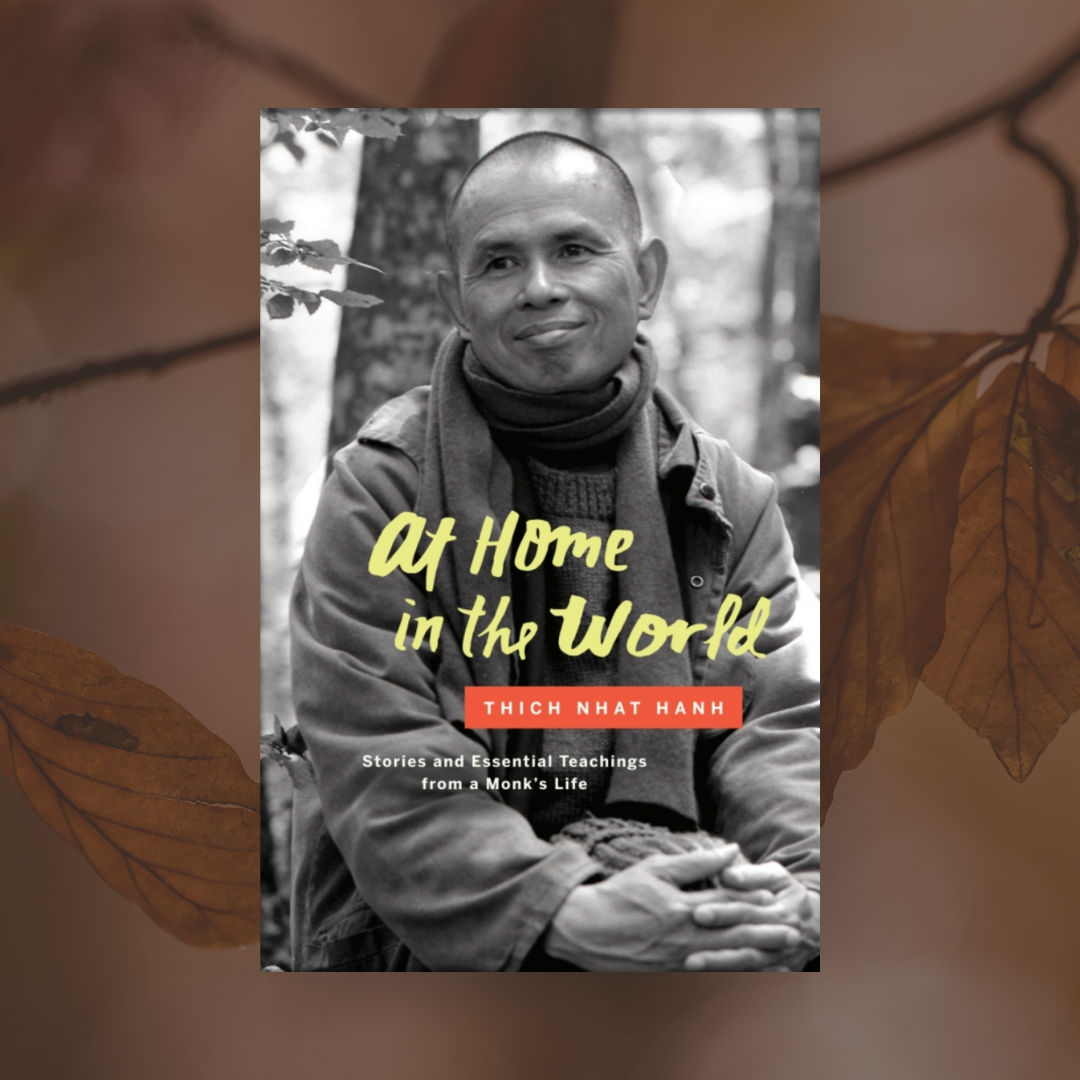

Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh recounts a powerful story of how he found his true home while exiled from his home country, Vietnam, for almost forty years.

“In 1968 during the Vietnam War, I went to France to represent the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation at the Paris Peace Talks. Our mission was to speak out against the war on behalf of the mass of Vietnamese people whose voices were not being heard. I was flying back from Japan, where I had been to give a public talk, and stopped in New York on the way to see my friend Alfred Hassler, of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an organization working actively to end the Vietnam war and promote social justice. But I didn’t have a transit visa, so when I landed in Seattle I was taken aside and led to a room where I was locked in and not permitted to see or speak to anyone. The walls were covered with Wanted posters picturing wanted felons. The authorities took my passport and wouldn’t allow me to contact anyone. It wasn’t until several hours later, when my flight was about to leave, that it was finally returned to me and I was escorted to the plane.

Two years earlier, in 1966, I was in Washington, DC, for a conference when a Baltimore Sun reporter informed me of a dispatch from Saigon urging the governments of the US, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan to no longer honor my passport because they felt I had been saying things opposing their efforts in the war against Communism. The governments complied, and my passport was invalidated. Some of my friends in Washington, DC, urged me to go into hiding, but to stay in the US would have meant risking deportation and jail.

So I didn’t go into hiding and instead sought political asylum in France. The French government granted me asylum, and I was able to obtain an apatride travel document. Apatride means you don’t belong to any country; you become stateless. With this document, I could travel to any European country that had signed the Geneva Convention. But to go to countries like Canada or the US, I would still need to apply for a visa, which is very difficult to do when you are no longer a citizen of any country. My original intention had been to only leave Vietnam for three months in order to give a series of lectures at Cornell University, and to make a speaking tour of the US and Europe to call for peace, and then to go home again. My family, all my friends and coworkers—my whole life—was in Vietnam. Yet I ended up being exiled for almost forty years.

Whenever I applied for a visa to go to the US, it would be turned down automatically. The government didn’t want me to go there; they believed I might harm the US war effort in Vietnam. I wasn’t allowed to go to the US and I wasn’t allowed to go to England either. I would have to write letters to such people as Senator George McGovern and Senator Robert Kennedy asking them to send me a letter of invitation. Their replies read something like this: “Dear Thich Nhat Hanh, I would like to know more about the situation of the war in Vietnam. Please come and inform me. If you have difficulties obtaining a visa, please telephone me at this number…” Only with such a letter could I get a visa. Otherwise, it was impossible.

I have to admit that the first two years of exile were quite difficult. Although I was already a forty-year-old monk with many disciples, I had still not yet found my true home. I could give very good lectures on the practice of Buddhism, but I had not truly arrived. Intellectually, I knew a lot about Buddhism: I had trained for many years in the Buddhist Institute and had been practicing since I was sixteen, but I hadn’t yet really found my true home.

My intention on the speaking tours in the US was to bring people information about the real situation in Vietnam that they weren’t hearing about on the radio and in the newspaper. During the tour, I would only sleep one or two nights in each city I visited. There were times when I woke up at night and didn’t know where I was. It was very hard. I had to breathe in and out and remember what city and country I was in.

During this time, I had a recurring dream of being at home in my root temple in central Vietnam. I would be climbing a green hill covered with beautiful trees when, halfway to the top, I would wake up and realize that I was in exile. The dream came to me over and over again. In the meantime, I was very active, learning how to play with children from many countries: German children, French children, American children, and English children. I was making friends with Anglican priests, Catholic priests, Protestant ministers, rabbis, imams, and others. My practice was the practice of mindfulness. I tried to live in the here and now and touch the wonders of life every day. It was thanks to this practice that I survived. The trees in Europe were so different from the trees in Vietnam. The fruits, the flowers, the people, they were all completely different. The practice brought me back to my true home in the here and now. Eventually I stopped suffering, and the dream did not come back anymore.

It was because I didn’t belong to any particular country that I had to make an effort to break through and find my true home.

Thích Nhất Hạnh, At Home in the World

People may think that I was suffering because I wasn’t allowed to go back to my home in Vietnam. But that’s not the case. When I was finally allowed to return, after almost forty years of exile, it was a joy to be able to offer the teachings and practices of mindfulness and Engaged Buddhism to the monks, nuns, and laypeople there; and it was a joy to have time to talk to artists, writers, and scholars. Nevertheless, when it was time to leave my native country again, I didn’t suffer.

The expression, “I have arrived, I am home,” is the embodiment of my practice. It is one of the main Dharma seals of Plum Village. It expresses my understanding of the teaching of the Buddha and is the essence of my practice. Since finding my true home, I no longer suffer. The past is no longer a prison for me. The future is not a prison either. I am able to live in the here and now and to touch my true home. I am able to arrive home with every breath and with every step. I don’t have to buy a ticket; I don’t have to go through a security check. Within a few seconds, I can arrive home.

When we are deeply in touch with the present moment, we can touch both the past and the future; and if we know how to handle the present moment properly, we can heal the past. It was precisely because I did not have a country of my own that I had the opportunity to find my true home. This is very important. It was because I didn’t belong to any particular country that I had to make an effort to break through and find my true home. The feeling that we are not accepted, that we do not belong anywhere and have no national identity, can provoke the breakthrough necessary for us to find our true home.”

Excerpt from At Home in the World by Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh

Copyright Parallax Press

At Home in the World: International Online Retreat

Deer Park Monastery invites you to join our sangha from wherever you are in the world for our international Online Retreat, At Home in the World.

March 20-24, 2024 | Register here

The retreat is in English with translation and registration available in Spanish, Vietnamese, and Mandarin Chinese.