By Mitchell Ratner on

Dharma teacher Mitchell Ratner reflects on his pilgrimage tracing Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life and lineage in Vietnam, granting him deeper understanding of Thầy and himself.

In 2019,

By Mitchell Ratner on

Dharma teacher Mitchell Ratner reflects on his pilgrimage tracing Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life and lineage in Vietnam, granting him deeper understanding of Thầy and himself.

In 2019, Sister Định Nghiêm told me about an idea that had been growing in her heart. She felt that many of the non-Vietnamese monastic and lay students of Thầy would better understand his teachings and practices if they were more familiar with the rich Buddhist history of Vietnam and with the events and places that had shaped Thầy’s life. Sister Định Nghiêm and I then began initial planning for a pilgrimage tour. Because of the COVID pandemic and Thầy’s declining health, however, the first In the Footsteps of Thầy pilgrimage was delayed.

After Thầy’s passing in 2022 and the easing of COVID concerns, Sister Định Nghiêm, working with Sister Tuệ Nghiêm, planned a pilgrimage for January 2023. The group of pilgrims met on January 6th in the spacious Hà Nội home of Vietnamese friends of Plum Village to begin an eighteen-day pilgrimage tour; some of us were able to participate in all of it, and others only in part of it. There were thirty of us—just the right number to comfortably fit in a Vietnamese tour bus. In the initial gathering there were eight Plum Village monastics (from Vietnam, France, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia), two Korean abbots, and about twenty lay practitioners (from the United States, Spain, France, Germany, Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore). Sisters Định Nghiêm and Tuệ Nghiêm, senior monastics from the New Hamlet of Plum Village, France, were at times our hosts, guides, historians of Thầy’s life, translators, and mother hens.

During the pilgrimage we spent nights in Hà Nội, Thanh Hóa, Đà Lạt, Huế, and Yên Tử Mountain, as well as one night on an overnight train. During our days we often traveled by bus to visit places important to Thầy’s development as a person and as a teacher. The pilgrimage was at various times a practice retreat with sitting and walking meditation; a study group with our organizing sisters and local guides offering presentations about the importance of places we would be visiting; and a container for multi-day, heart-to-heart conversations about our lives and our practice of Engaged Buddhism. It was, in a word, intense!

Five encounters touched me especially deeply and helped me understand Thầy in new ways: Thanh Hóa and Na Mountain, Chùa Dâu (the first Buddhist monastery in Vietnam), the enlightened kings of the Trần Nhân Dynasty, Yên Tử Mountain, and Từ Hiếu Temple.

Thanh Hóa and Na Mountain

One of our first destinations was the city of Thanh Hóa, where Thầy’s family moved when he was five years old. We arrived late in the morning and had a simple lunch at a small vegetarian restaurant in the old part of town, which happened to have a quote from and photo of Albert Einstein next to the cash register. In the afternoon a visit to an archeological museum stimulated my interest in the history of Vietnam and in how it had shaped Thầy’s life and teaching—a way of looking at the world influenced by my training and work as a social anthropologist. Prior to the pilgrimage, almost everything I knew about Vietnamese history took place in the twentieth century.

The primary focus of the archaeological museum in Thanh Hóa was the Dong Son culture, which arose around three thousand years ago in the Red River Valley and Delta, roughly coterminous with contemporary North Vietnam. The Dong Son were proficient in cultivating rice and skilled in casting bronze tools. In time a geographically extensive, hierarchical, state-like structure arose, led by hereditary rulers who created and maintained hydraulic systems for agricultural cultivation and flood protection, managed trade, and prevented attacks and invasions. Between the years 43 and 299 CE, the agriculturally productive Red River Valley area was part of an administrative district called the Jiaozhi Commandery (Quận Giao Chỉ). Although the population was primarily Vietnamese-speaking, they were ruled by Chinese dynasties.

Our hotel in the modern center of Thanh Hóa was ten-stories high and bland, with few other guests. However, the emptiness of the lobby was helpful that night because an attached dining area offered the hotel’s strongest Wi-Fi signal. At 9:00 p.m. Vietnam time, which was 9:00 a.m. in the Eastern United States, I participated in an in-person and online ceremony transmitting The Five Mindfulness Trainings to practitioners in the Washington DC area. Logging into the internet at the hotel and remembering the Einstein quote at our lunch, I was struck by how much more worldly Thanh Hóa was today from the provincial town Thầy knew in the 1930s.

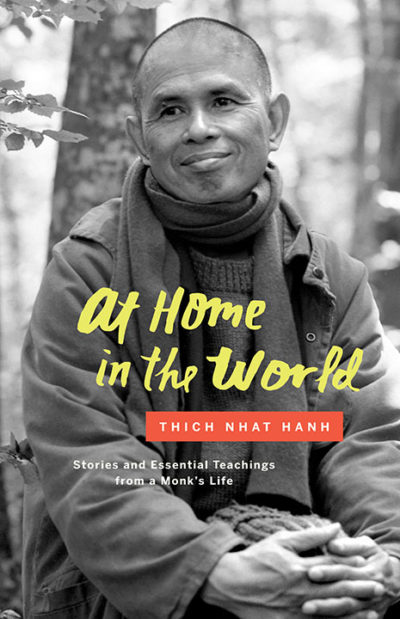

The next morning we traveled by bus to Na Mountain, one of the three most sacred locations in Vietnam. Thầy visited the mountain on a school trip as an eleven-year-old. He had hoped to meet a hermit who his teacher had told him lived on the mountain. Going off on his own, Thầy found the hermit’s simple hut, but not the hermit. Then he found something else that changed the course of his life. Thầy called it his first spiritual experience. In At Home in the World he writes:

As I walked deeper into the forest, I heard the sound of dripping water. It was a beautiful sound. I started to climb in the direction of that sound, and soon I found a natural well, a small pool surrounded by big rocks of many colors. The water was so clear that I could see all the way to the bottom.… The water tasted so good. I had never tasted anything as good as that water. I felt completely satisfied; I did not need or want anything at all—even the desire to meet the hermit was gone. I had the feeling that I had met the hermit.1

Our group sat in meditation by a feng shui shrine at the top of the mountain. The hermit’s hut was long gone. However, we were able to walk down the mountain to gather around the well and taste its water.

Thầy’s visit to Na Mountain contributed to his aspiration to become a monk. When he was sixteen he traveled by overnight train from Thanh Hóa to Huế to become a novice at Từ Hiếu Temple, accompanied by his older brother, who was already a monk there. Our pilgrimage group replicated Thầy’s journey by taking an overnight train to Huế. I shared a sleeping compartment with the Korean abbots, both of whom exuded a joyful settledness that drew me and others to them. Although neither of them spoke English well, and their female translator was in a different compartment, we managed that night and the next morning to have some delightful exchanges using gestures and Google Translate.

Chùa Dâu and Master Tăng Hội

Later in the pilgrimage we drove thirty miles from Hà Nội to visit Chùa Dâu, the first Buddhist Temple in Vietnam. It was built between 187-226 CE in what was then Luy Lâu, the capital of the Jiaozhi Commandery. Because of its prominent role in the sea trade between India and China, Luy Lâu was often visited by Indian monks and traders, and the area became a regional hub for the study and teaching of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

For Thầy, Chùa Dâu was especially important because Master Tăng Hội, who died in 280 CE, studied and taught there. In 2007, after his second trip home after his exile from Vietnam, Thầy explained:

The meditation that I share in the West has its roots in Vietnam of the third century. We had a very famous Zen master, Master Tăng Hội, whose father was a soldier from India and his mother a young Vietnamese woman. When his parents passed away, the child Tăng Hội went to a temple in northern Vietnam to become a monastic. He translated commentaries on the sutras in that temple in Vietnam, then went to China where he became the first Zen master teaching meditation in China—three hundred years before Bodhidharma. I wrote a book about Zen Master Tăng Hội, and I said that Vietnamese Buddhists should worship this Zen master as our first Zen master of Vietnam.2

In light of the significance of Chùa Dâu to Thầy, our visit to the temple unfolded in a surprising way. The temple seemed unfrequented and somewhat neglected. Although there were statues of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, there were many more statues honoring local deities, Chinese mandarins, and guardian spirits. Our local guides enthusiastically told us fanciful stories, including one about a young woman who had been transformed into a tree by a dishonorable monk, then centuries later was released by a wise local lord who had the fallen tree made into a yellow-robed statue that now towered over the Buddha in the central altar. Throughout our tour of the temple, the guides never mentioned Master Tăng Hội.

Later, away from the guides, Sister Định Nghiêm explained that Vietnamese Buddhism continues to coexist with many folk beliefs and practices involving local deities, mother goddesses, ancestral gods, shamans, and animal spirits. In some temples, such as this one, these other perspectives play a much more prominent role.

Our visit to Chùa Dâu helped me appreciate Thầy’s spiritual connection with Vietnam’s two-thousand-year-old Buddhist heritage. Because of his fluency in Vietnamese and Sino-Vietnamese, if there was something a Vietnamese-Buddhist teacher had written, he could read it. Thầy, however, was not only a historian and aficionado of Vietnamese Buddhism; he was also a spiritual revolutionary. Beginning in his teens, Thầy had a deep desire to renew and revitalize Buddhism in Vietnam. He wanted to move the Buddhist community away from the superstitions and folk beliefs we brushed up against at Chùa Dâu and to offer more nourishing spiritual practices, like those Tăng Hội had contributed to the Buddhist tradition.

The Enlightened Kings

Thầy began monastic training at Từ Hiếu in 1942, in the midst of the Second World War. Japanese control and subsequent occupation caused many hardships for Từ Hiếu and for all of Vietnam, especially the Great Famine of 1945 when an estimated 600,000 to 2,000,000 Vietnamese people died. Thầy’s biography notes:

Stepping out of the temple [Thầy] saw bodies out in the streets of those who had died of hunger and witnessed trucks carrying away dozens of corpses. When the French returned to reclaim Vietnam in 1945, the violence only increased. Although many young monks were tempted by the Marxist pamphlets’ call to arms, Thầy was convinced that Buddhism, if updated and restored to its core teachings and practices, could truly help relieve suffering in society and offer a nonviolent path to peace, prosperity, and independence from colonizing powers, just as it had during the renowned Lý and Trần dynasties in medieval Vietnam.3

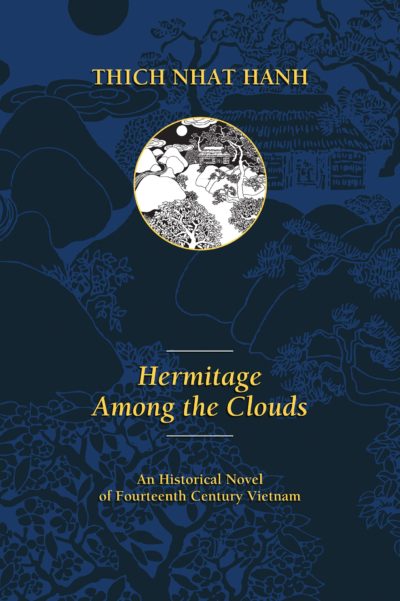

To learn more about the medieval emperors that so inspired Thầy, our pilgrimage group traveled to Yên Tử Mountain, seventy miles east of Hà Nội. The first three Trần Dynasty emperors, who ruled from 1226 to 1314, especially impressed me because they were effective military leaders, compassionate rulers, supportive mentors to their sons, and fully committed Buddhist practitioners. After the decisive defeat of the Mongols armies, Trần Nhân Tông, the third Emperor of the Trần Dynasty, focused on rebuilding his country and reducing the burden on the poor. When he was thirty-two, he abdicated in favor of his son. Trần Nhân Tông had wanted for years to devote himself to spiritual awakening. After officially becoming the “Retired Emperor,” he left the palace to practice Buddhism on Yên Tử Mountain, ordaining as a monk in 1295.

In the preface to his historical novel Hermitage Among the Clouds, Thầy writes about Trần Nhân Tông:

[He] abdicated his throne to become a monk and live in the little hermitage “Sleeping Clouds” on Mount Yên Tử. He was known as the “Noble Teacher of Bamboo Forest” and was the founder of the “Bamboo Forest School of Zen Meditation.”

Before becoming a monk … he ruled as king over the land of Viet. He repelled the invading Mongol army at the end of the thirteenth century. From the day he was ordained a monk, he lived an ascetic life—wearing coarse cloth, sleeping under a roof of leaves, and going everywhere barefoot. Even as a monk, he continued his work to establish justice and morality in the culture of his people. He traveled to the land of Cham in hopes of establishing a foundation of lasting friendship and peace between the two countries.4

Several days before his death, Trần Nhân Tông inscribed a poem on a temple wall:

Life’s length is one breath, Moonlight on ocean waves. Why worry about Mara’s realm? My Buddha land is the springtime sky.5

Yên Tử Mountain

Our group’s time on Yên Tử Mountain was divided between two very different environments. We stayed overnight and ate most of our meals in a recently-built resort complex created to resemble a twelfth-century Vietnamese monastery or town. The complex included a five-star hotel for “royalty” as well as modest rooms containing four bunk beds for “villagers” (including our group). The whole town, and especially the five-star hotel, were meticulously crafted and luxurious. Although there were many gorgeous landscaped views and lovely architectural details, the overall effect felt to me discordant with the natural simplicity of Yên Tử Mountain and the Bamboo Forest School founded by Trần Nhân Tông.

The other environment we experienced was Yên Tử mountain: rugged, wild, and full of Buddhist and Taoist temples and sacred spots. We climbed Yên Tử in a biting wind with the temperature around fifty degrees Fahrenheit. A few monastics and lay practitioners climbed for three hours on stone stairs and heavily rooted paths. The rest of us accepted the assistance of gondolas on two segments. Even then, the way up was arduous. Along the way, we did prostrations and walking meditation at a fourteenth-century stupa containing the relics of Trần Nhân Tông. The view from the peak was a spectacular panorama of multiple ranges of cloud-covered mountains. We stayed for an hour, resting, sharing snacks and reflections, and singing Plum Village songs.

Later, when I talked with friends about the early Trần emperors, one asked me how their teachings and practices might be applicable today. What sort of reforms or strategies might such enlightened rulers advocate? My sense is that it is not about specific reforms or strategies, but about leaders nourishing in themselves and others an aspiration to be loving, compassionate, and fully awake. If that perspective is present in many, positive changes will occur. Thầy said something very similar in a Dharma talk:

In Buddhism we speak of the Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. But when we look at the Sangha, the third Jewel, we see that it contains the two other Jewels. A good Sangha, a good community, is made of people who practice mindfulness, concentration, and insight. …

So in a Sangha, in the body of the Sangha, because we have a good Sanghakaya (Sanghabody), there are many cells. Each of us is a cell of the Sangha. And each of us can generate the energy of mindfulness, concentration, and insight. And if every one of us practices properly, then the collective energy produced by the Sangha will be very powerful.

I think that we can save this planet, reduce violence, and end war with that kind of energy. No matter how talented our political leaders are, if they do not have that kind of energy, they cannot help.… Martin Luther King Jr. saw that very well. He was devoted to Sangha building. He talked about the Sangha as a beloved community. Unfortunately he was assassinated and could not continue the work of Sangha building. We should continue his work, because Sangha building is very crucial. It is by the work of Sangha building that we can create the kind of power, the kind of energy, that helps us to deal with the enormous difficulties we are now facing.6

Từ Hiếu Temple

Thầy lived at the Từ Hiếu Temple in Huế for five years as an aspirant and novice and returned there for the final four years of his life. Our pilgrimage made two multi-day visits to Từ Hiếu to participate in the ceremonies honoring the first anniversary of Thầy’s passing and, later, to celebrate Tết with the monastic community. I had practiced at Từ Hiếu in prior years and have warm feelings for it because of its connection to Thầy, because of the kindnesses I have received from the monastics who practice there, and because of its engaging history.

The story of Từ Hiếu begins in the mid-nineteenth century. National Teacher Master Thích Nhất Định was the esteemed abbot of a temple in Huế and also an advisor to the Nguyễn Dynasty court. When he was fifty-nine years old, he retired and moved to a straw hut in the pine woods outside Huế. Some time later his elderly mother, whom he cared for at his hermitage, became ill and doctors recommended a diet of fish soup. Although as a Buddhist monk he was a committed vegetarian, Thích Nhất Định dutifully walked to the market every morning to buy fish. When people began to spread rumors about his dietary laxness, Nhất Định did not respond.

In time the story reached the court of Emperor Tự Đức, a learned and kind leader who was a strong follower of Confucian ethics. He investigated and realized Nhất Định’s actions were prompted by his love for his mother. In 1848, the year after Nhất Định’s death, the emperor honored the faithful monk by building a major temple at the site of the straw hut. He named the temple Từ Hiếu, “Merciful Filial Piety.”

I envision the monastery as exquisite and well maintained in its early years, but its appearance and finances were probably much reduced by 1942 when Thầy came to Từ Hiếu as an aspirant monk. Even though the physical conditions were difficult, Thầy remembers Từ Hiếu fondly in his memoir, My Master’s Robe:

Of course you did not practice sitting meditation all day when you entered the temple. For months and sometimes years you had to take care of the cows, collect dry twigs and leaves, carry water, pound rice, and collect wood for the fire. Every time my mother came to visit from our village, which was far away, she would regard these things as being the challenges of the first stage of practice. At first my mother was concerned for my health, but as I grew healthier, she stopped worrying about me. As for me, I knew that these were not challenges—they were themselves the practice. If you enter this life, you will see for yourself. If there was no taking care of the cows, no collecting of twigs and leaves, no carrying water, no growing potatoes, then there would be no means for the practice of meditation.7

During the Tết celebration our group met one morning for meditation at “Thầy’s Hut,” where Thầy lived his final years. Thầy’s presence was palpable. Then we went to the Buddha Hall to pay our respects to the Buddha and to the Từ Hiếu Temple lineage. I remember standing, spellbound, in front of two portraits framed together in the ancestors’ room. One portrait was of Thầy’s teacher, Abbot Thích Chân Thật (1884-1968), and to the right was Thầy’s teacher’s teacher, Abbot Thích Tuệ Minh (1861-1939). The portraits led me to reflect on the transmission of the mindfulness teachings from generation to generation, beginning with the Buddha and continuing to Thầy and the many lives he touched and transformed.

The portraits also reminded me that the essence of a spiritual practice is transmitted through close and loving relationships. In My Master’s Robe Thầy writes about discovering his teacher up very late one night stitching a brown robe. Soon Thầy realizes that his teacher is mending the robe so he can offer it to Thầy in the morning, when he will receive the novice precepts and will no longer wear the gray robes of an aspirant.

At last the robe was mended. My teacher signaled for me to come closer. He asked me to try it on. The robe was a little too large for me, but that did not prevent me from feeling so happy that I was moved to tears. I had received the most sacred kind of love—a pure love that was gentle and spacious, which nourished and infused my aspiration through my many years of training and practice.8

The last time Thầy visited his teacher at Từ Hiếu was in May 1966, just before Thầy traveled to the US to speak about the horrific suffering caused by the war and to call for peace. Thầy received Lamp Transmission during the visit, becoming one of many Dharma heirs of Master Thích Chân Thật. Two years later, when the abbot died, he left instructions for Thầy to be appointed as the abbot of Từ Hiếu. Thầy, however, because of his peace advocacy in the US, was denied the right to return to Vietnam and was not able to visit Từ Hiếu again until 2005.

Healing and Transformation

I signed up for the pilgrimage expecting it to deepen my understanding of Thầy and his teachings, and it did. I didn’t expect how much it would teach me about myself.

As I’ve noted, the pilgrimage made me more aware of how deeply Thầy experienced and was nourished by his relationships with his ancestors. Once I saw that, I began noticing it all around me in Vietnam: in the space and care devoted to family altars and in the way visits to family and temples are an integral part of the celebration of the Vietnamese New Year.

The more clearly I saw these Vietnamese connections, the more I became aware of the paucity of my own connections to my blood, land, and spiritual ancestors. My grandparents were Eastern European Jews, shopkeepers and tailors, who came to the United States as teenagers around 1900. They left behind the communities they had grown up in, the languages they were accustomed to speaking, parents and extended families, and the spiritual traditions that had nourished earlier generations. Shortly after I was born, my parents relocated from the Midwest to California, separating themselves from their own extended families. I grew up rootless, unhappy, and without a sense of belonging anywhere. Looking for something better, and wanting to distance myself from family tensions, I moved from California to the Washington DC area in my twenties.

I struggled with my rootlessness for another two decades, and then I met Thầy in 1990. I realized I had a spiritual illness that I didn't even know how to talk about. But Thầy understood it, and he (and the Buddha) had a remedy. Thầy offered me a vision of a life fully and authentically lived, concrete practices to develop my mindfulness and compassion, and a community of spiritual companions. In other words, Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Often during the pilgrimage I thought about the almost forty years during which Thầy could not visit Vietnam. He so loved the country and its history; he cared deeply for his many friends and teachers at Từ Hiếu and throughout Vietnam who had supported and nourished him. How painful it was for him to be separated from them. In an odd sort of way, both Thầy and I had lived much of our lives in exile. His was geographic. Mine was a form of psychological and spiritual alienation, a decaying of my capacity to relate well to myself, those around me, and the natural world.

Fortunately, the practices that were helpful to Thầy in his exile, were also helpful to me and to millions of others. In At Home in the World Thầy writes about his first two years of exile:

I had a recurring dream of being at home in my root temple in central Vietnam. I would be climbing a green hill covered with beautiful trees when, halfway to the top, I would wake up and realize that I was in exile. The dream came to me over and over again.9

Over time he learned to embrace his exile and the profound insights it made available to him:

My practice was the practice of mindfulness. I tried to live in the here and now and touch the wonders of life every day. It was thanks to this practice that I survived. The trees in Europe were so different from the trees in Vietnam. The fruits, the flowers, the people, they were all completely different. The practice brought me back to my true home in the here and now. Eventually I stopped suffering, and the dream did not come back anymore.…

The expression, “I have arrived, I am home,” is the embodiment of my practice. It is one of the main Dharma Seals of Plum Village. It expresses my understanding of the teaching of the Buddha and is the essence of my practice. Since finding my true home, I no longer suffer.…

When we are deeply in touch with the present moment, we can touch both the past and the future; and if we know how to handle the present moment properly, we can heal the past. It was precisely because I did not have a country of my own that I had the opportunity to find my true home.10

I am deeply grateful to Thầy for offering his reparative teachings to Western practitioners. I am grateful to Sister Định Nghiêm for imagining all that an In the Footsteps of Thầy pilgrimage might offer non-Vietnamese practitioners. It certainly touched and transformed me more deeply and in more ways than I anticipated. I am filled with gratitude for Sisters Định Nghiêm and Tuệ Nghiêm, who worked tirelessly before and during the pilgrimage, and for the many wonderful practitioners on the pilgrimage bus with whom I shared joys, challenges, and emerging insights.

1 Thích Nhất Hạnh, At Home in the World (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2016), pages 23-24.

2 Thích Nhất Hạnh, “The Three Spiritual Powers,” The Mindfulness Bell 46 (October 2007)

3 “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography,” Plum Village. Accessed August 31, 2023.

4 Thích Nhất Hạnh, Hermitage Among the Clouds (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2001), page vii.

5 Thích Nhất Hạnh, Hermitage Among the Clouds (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2001), page 126.

6 Thích Nhất Hạnh, 2011, “Beloved Community,” Thích Nhất Hạnh

7 Thích Nhất Hạnh, My Master’s Robe (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2005), page 22.

8 Thích Nhất Hạnh, My Master’s Robe (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2005), page 97.

9 Thích Nhất Hạnh, At Home in the World (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2016), page 13.

10 Thích Nhất Hạnh, At Home in the World (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2016), pages 13-14.