Order of Interbeing member Mick McEvoy and Dharma Teacher Aaron Solomon share about community farming as love in action.

By Mick McEvoy, Aaron Solomon on

Amidst these divisive times, the Plum Village Happy Farm project in France, now in its thirteenth year, continues to bring together people from all over the world to practice mindfulness and grow food for our communities.

Order of Interbeing member Mick McEvoy and Dharma Teacher Aaron Solomon share about community farming as love in action.

By Mick McEvoy, Aaron Solomon on

Amidst these divisive times, the Plum Village Happy Farm project in France, now in its thirteenth year, continues to bring together people from all over the world to practice mindfulness and grow food for our communities. This past winter, we experienced a legendary moment as Deer Park Monastery (California, US) broke ground on its own Happy Farm project. The now global Happy Farm project is not passive in the face of the present global political and social situation. Our Happy Farm project is radically political in its contribution to the evolution of local and global food systems. Collectively, we view the work we undertake as spiritual activism in the face of the polycrisis, as we act directly on behalf of climate, nature, and our society. We take pride in acting as a catalyst for other forms of activism in these realms that manifest all over the world. Happy Farm is committed to building sangha and common unity. We share the aspiration to cultivate a foundation of spiritual friendship, kindness, and understanding, supporting personal and collective stability, capacity, healing, and transformation.

I had the good fortune to be able to travel to Deer Park Monastery this past winter to offer what experience and skills that I could to help Deer Park Happy Farm come to life. Thầy Pháp Dung and Thầy Pháp Lưu are two of the tall trees in the monastic sangha at Deer Park Monastery. They are trailblazers and manifesters. Together with the equally dynamic efforts, energies, skills, and experience of long-term lay residents Aaron Solomon, Nikolay Amirov, and Josh Sowers, they have helped create the conditions for Deer Park Happy Farm to come into existence at this time when the world is no longer practicing ‘business as usual.’

I asked Aaron to share what the creation and development of Deer Park Happy Farm has meant to him in relation to building community in these divisive times.

—Mick McEvoy

In these divisive times, a revolutionary act of resistance at the center of Plum Village practice is simple yet profound: feeding each other. This is the miracle of generosity. If we want peace in the world, we must be able to feed everyone. When we start to give the little bit that we have, everyone is inspired to give. Suddenly we have an enormous amount of generosity and enough to feed everyone. It seems very simple and straightforward. Yet it can be a miracle, a source of wonder, joy, and celebration.

At Deer Park Monastery, we have just started a new Happy Farm, which has been bringing us so much joy. Volunteers have been coming on Saturdays to help build the farm; over sixty volunteers joined our first Happy Farm community work day on March 8, 2025. On the farm, our aspiration is to work in solidarity and mindfulness, following our breath, celebrating together the tender shoots of the new plants, and lending our effort together. In this way we touch joy and the work does not feel like a burden at all. After our morning working time, we join the entire community for a shared meal, very much in line with the teachings of generosity and feeding everyone.

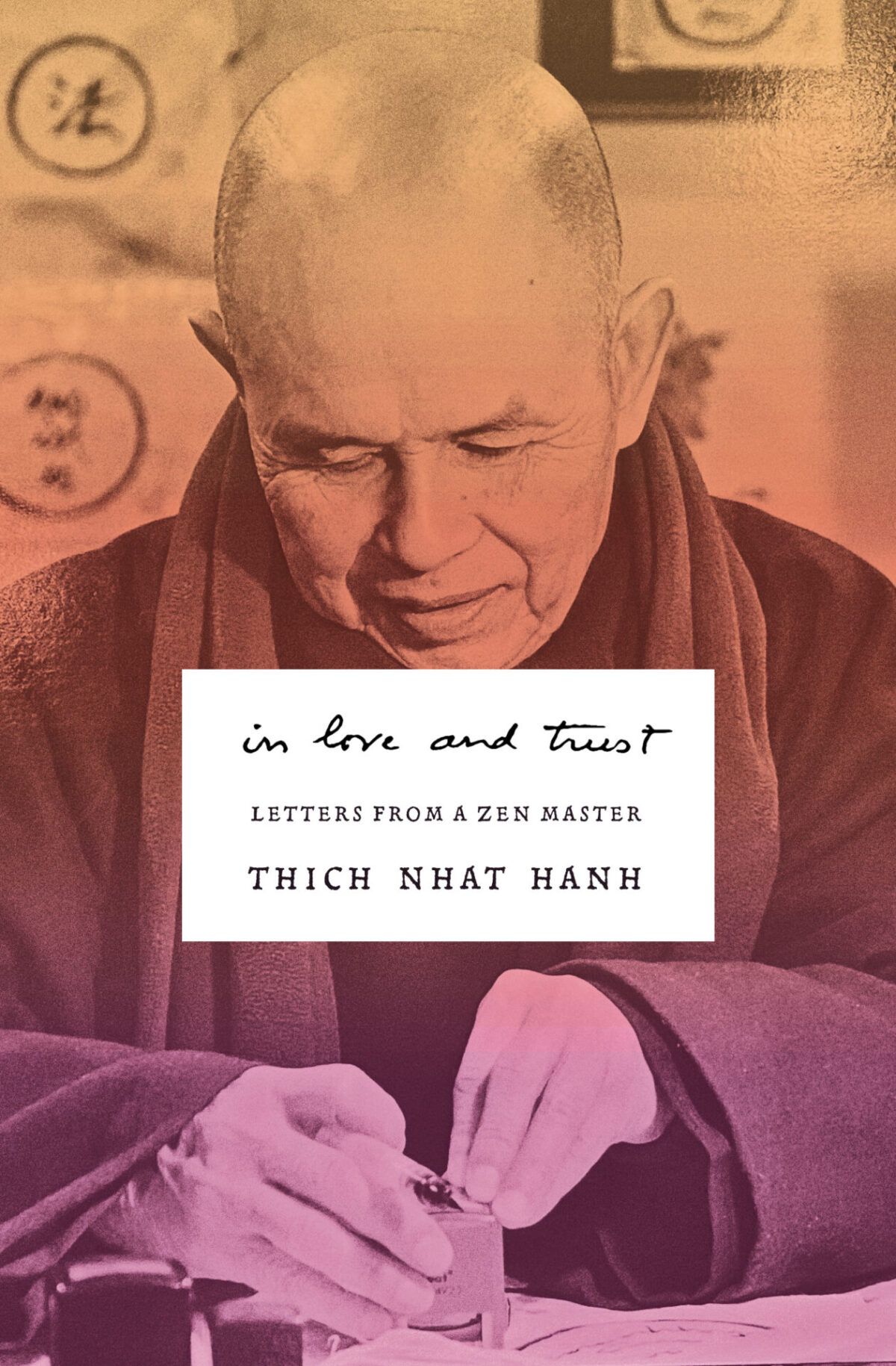

Through this shared work on the land, we embody a concrete act of resistance; this is our love in action. We want to build a farm together so that we can feed everyone without extracting or oppressing anyone. The revolutionary act of sharing resources, of building a community of harmony and understanding, is itself nonviolence. In Thích Nhất Hạnh’s early vision of community, he saw cooperative land stewardship as a way of creating interdependence without exploitation.1 He envisioned communities where “members of the village co-op are responsible for helping each other” and where “nobody can be indifferent.” When one person suffers, everyone is affected. This radical interconnection stands in stark contrast to our current society’s emphasis on individualism, extraction, and wealth accumulation. By cultivating the land together, we’re also cultivating a different way of seeing ourselves—not as separate, isolated beings, but as integral parts of a living, breathing whole.

Each of us has a longing to reconcile. In our tradition, we see that we cannot do this by force, but can do it through building understanding around our shared humanity. We see that the simple acts we do every day in community—walking meditation, eating together, working together down on the farm, or just taking care of our hamlet—all those actions in mindfulness are seeds for the possibility of healing. In these divisive times, these seemingly ordinary acts become profound statements of another way of being. When we dig our hands into the soil together, when we share the harvest, and when we break bread at the same table, we’re creating sacred spaces where healing can happen across the deepest divides.

The practice of farming mindfully teaches us confidence in the path of transformation—in ourselves and others. The tiniest and most ancient of life forms, thermophilic bacteria, as they transform compost into soil, continue day after day in the work of patient transformation. This is their love in action. In many ways, they are the foundation of our farm. These beings remind us that our own suffering and conflict, when held lovingly in community, can begin to transform. In these times of division and violence, our practice of cultivating community, of feeding each other and sharing generosity, is crucial for generating the strength and love we need to call for an end to violence, and for the transformation of oppression and the healing of wounds.

1 Thích Nhất Hạnh, In Love and Trust: Letters from a Zen Master (Parallax Press, 2024), 131-143.

Author’s note: An earlier version of this article included a footnote describing Thích Nhất Hạnh’s 1973 interest in Israeli moshav cooperative village models as potential applications for Buddhist community development. While we honor Thầy’s exploration of cooperative principles and recognize the idealism of many young Israelis—the sharing of resources, mutual aid, and collective responsibility—we recognize that the context, both historically and today, is inseparable from settler-colonialism, ongoing oppression of Palestinians, and genocidal violence in Gaza. Through the practice of nondiscrimination, we understand that valuable insights and harmful systems can emerge from the same source; we can learn from cooperative principles while clearly naming the injustice of their context. The cooperative ideals Thầy sought can and must be pursued through models that include and care for all neighbors, embodying the practice of dwelling together harmoniously. We have simplified the footnote to affirm our commitment to the path of transformation, justice, and healing, for a future to be possible.